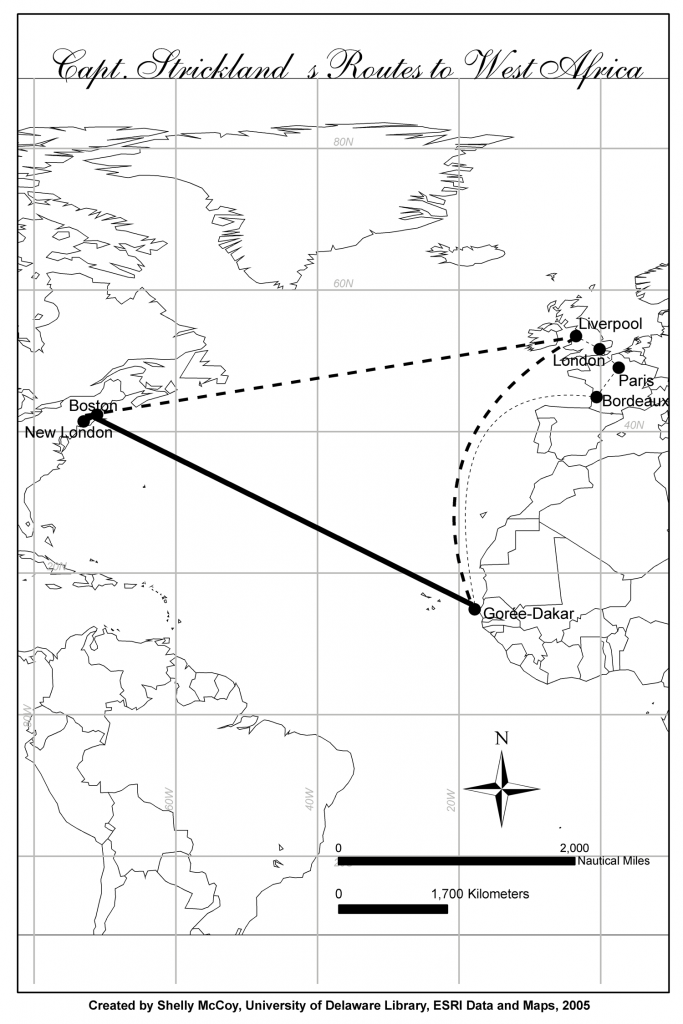

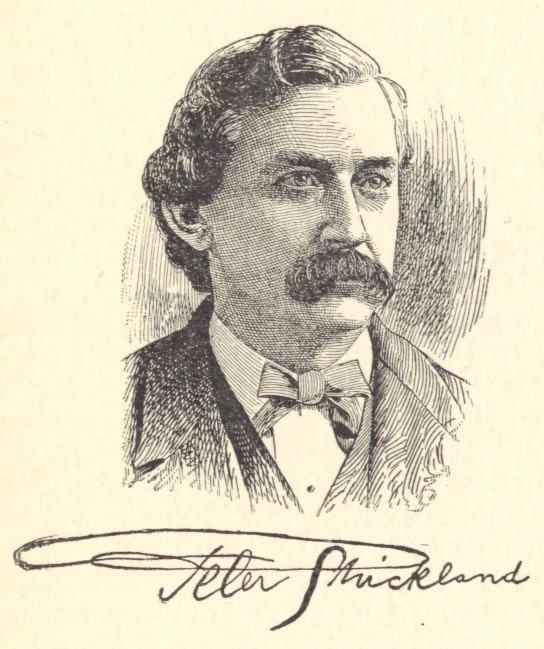

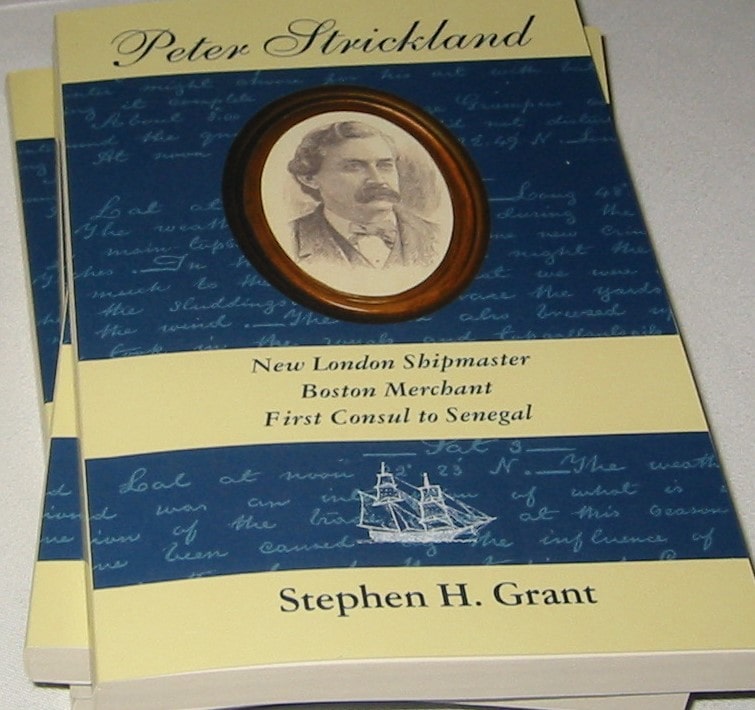

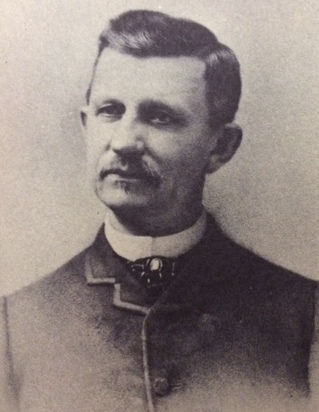

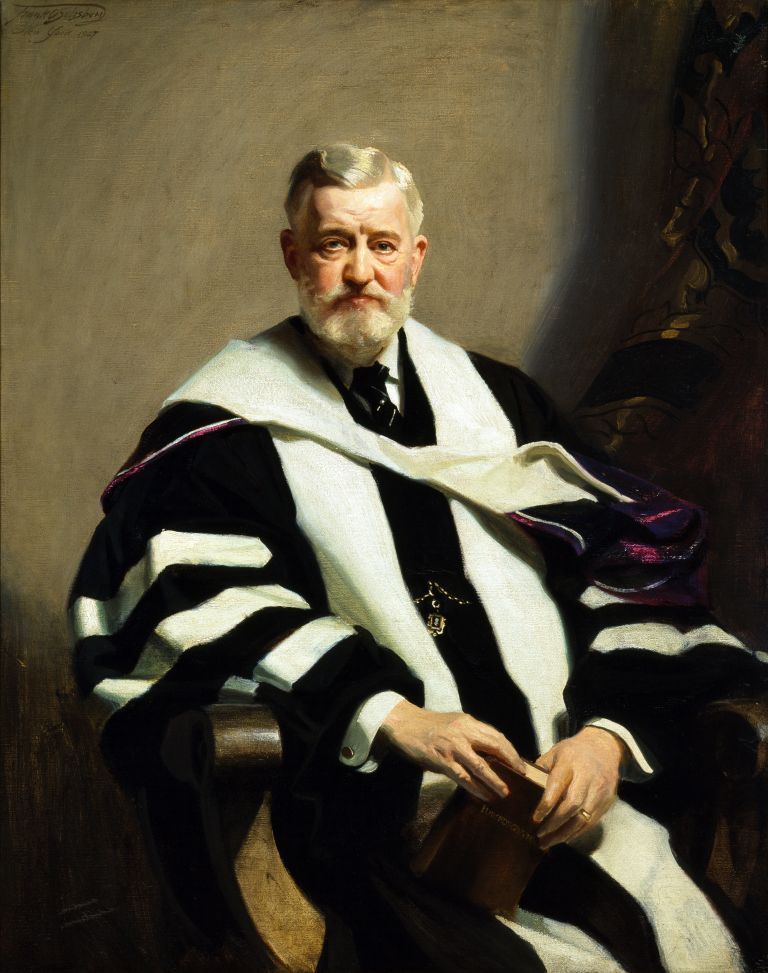

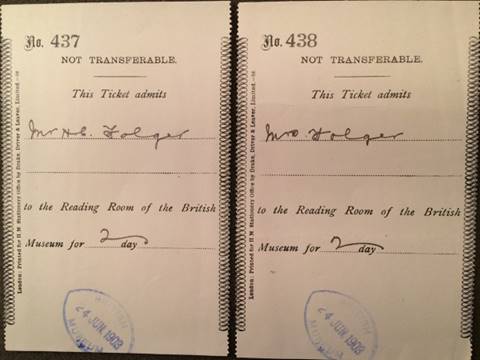

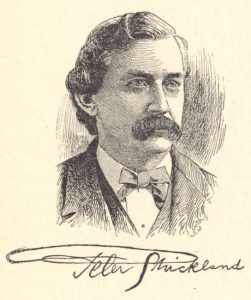

For a quarter of a century––from 1880 to 1905––shipmaster Peter Strickland lived on Gorée Island in Senegal while toiling in the merchant marine. He brought leaf tobacco from Kentucky and Tennessee to West Africa and, on return trips, filled the cargo bay of schooners with goat hides, peanuts, and palm kernels. In addition, he represented the United States as Consul, after his appointment by President Chester Arthur in 1883. Strickland was born in 1837 in Montville, Connecticut, and left school at age 15 for a seafaring life. In ten years he had risen from cabin boy to captain. He married Mary Louise Rogers who bore him four children: Peter, Grace, George, and Mary. Peter died of bronchitis at 10 mos. The family moved from New London to Dorchester, Massachusetts to be near the busy port of Boston. After trying to get used to living in West Africa, Mary Louise must have told her husband, “See you in Dorchester.” The older daughter stayed with the mother, the other two accompanied their father to Senegal. The couple lived apart for 25 years. From several statements in Strickland’s journal one concludes that the couple had a flawed marriage.

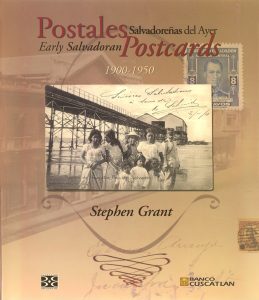

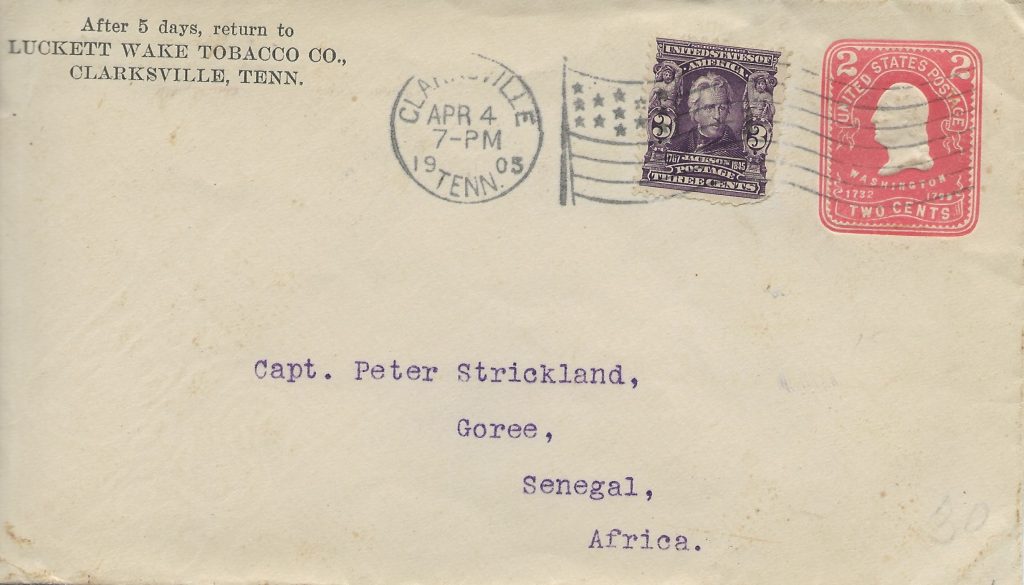

Fig.1. Captain Strickland’s Routes to West Africa Shelly McCoy,

University of Delaware Library, ESRI Data & Maps, 2005

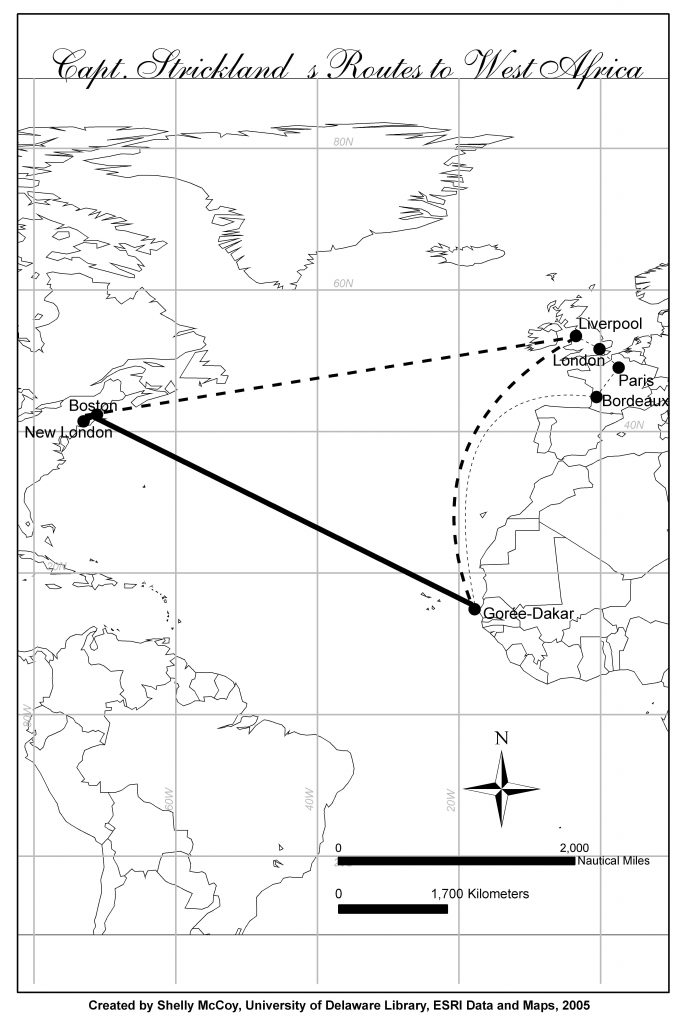

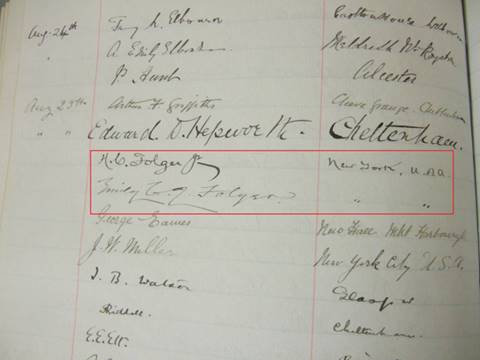

Fig.2. Captain Strickland’s West Africa Shelly McCoy,

University of Delaware Library, ESRI Data & Maps, 2005

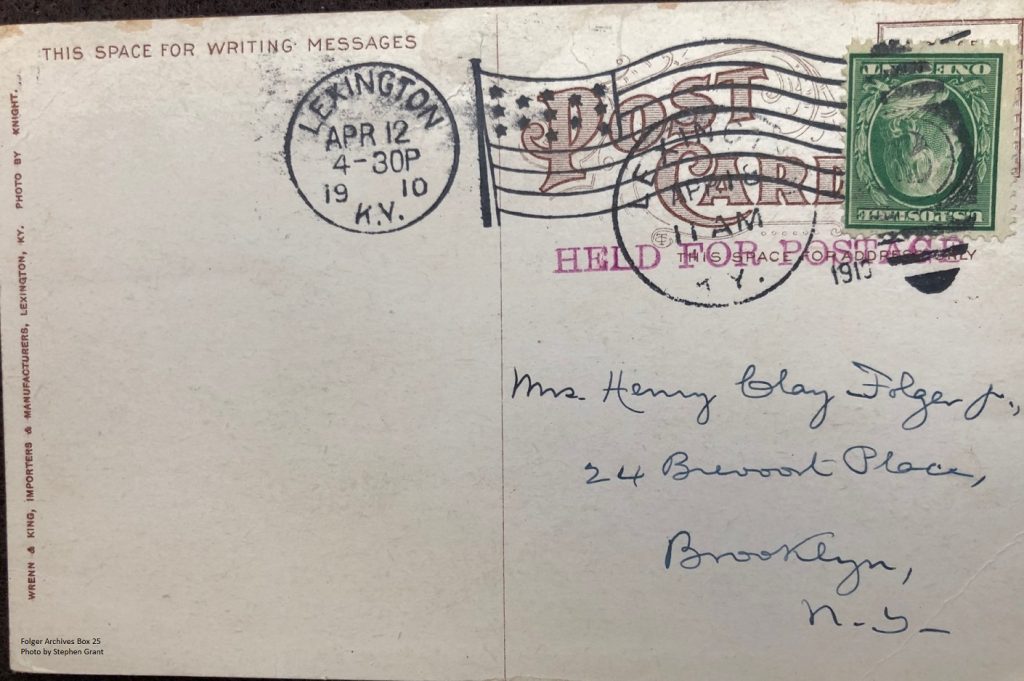

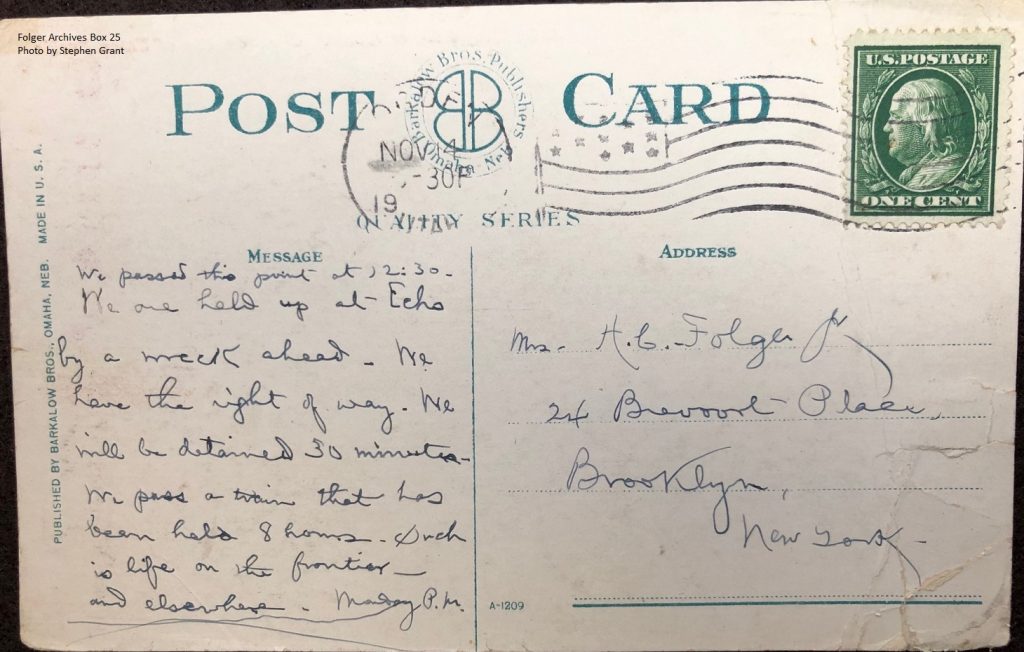

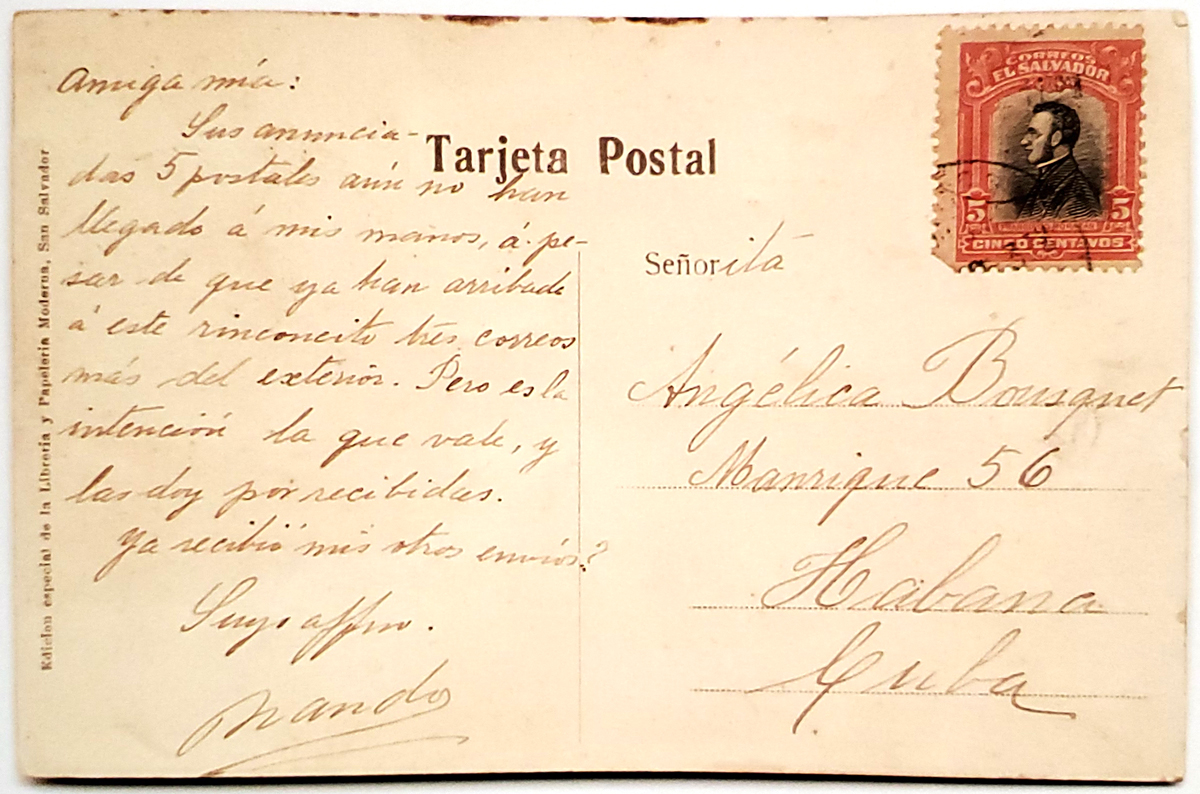

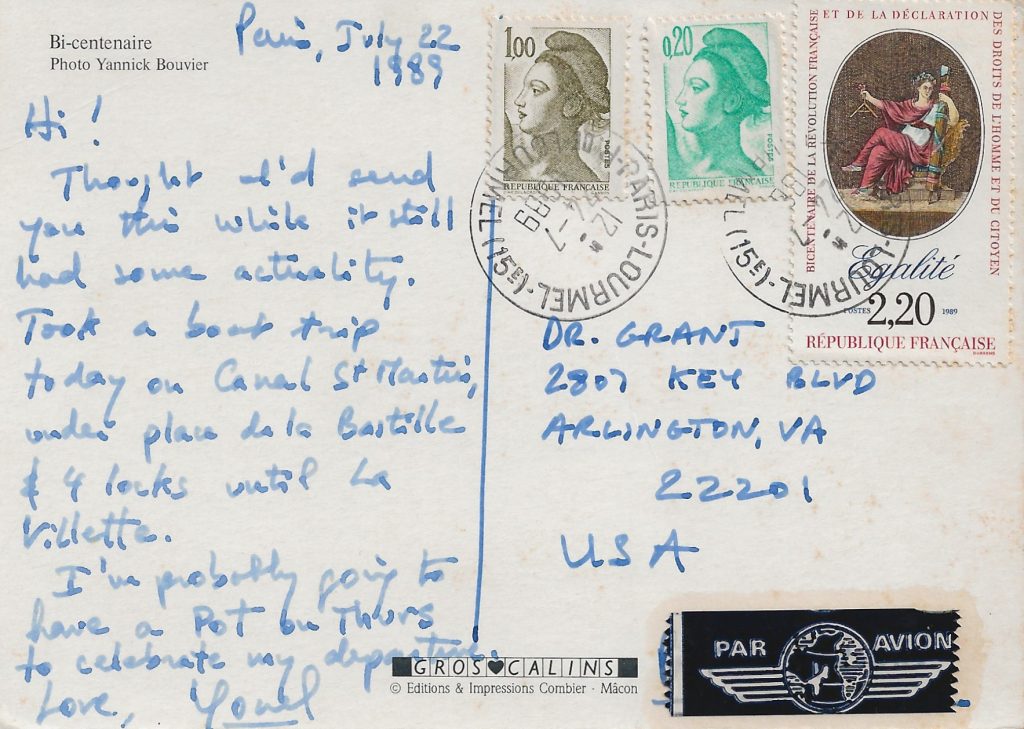

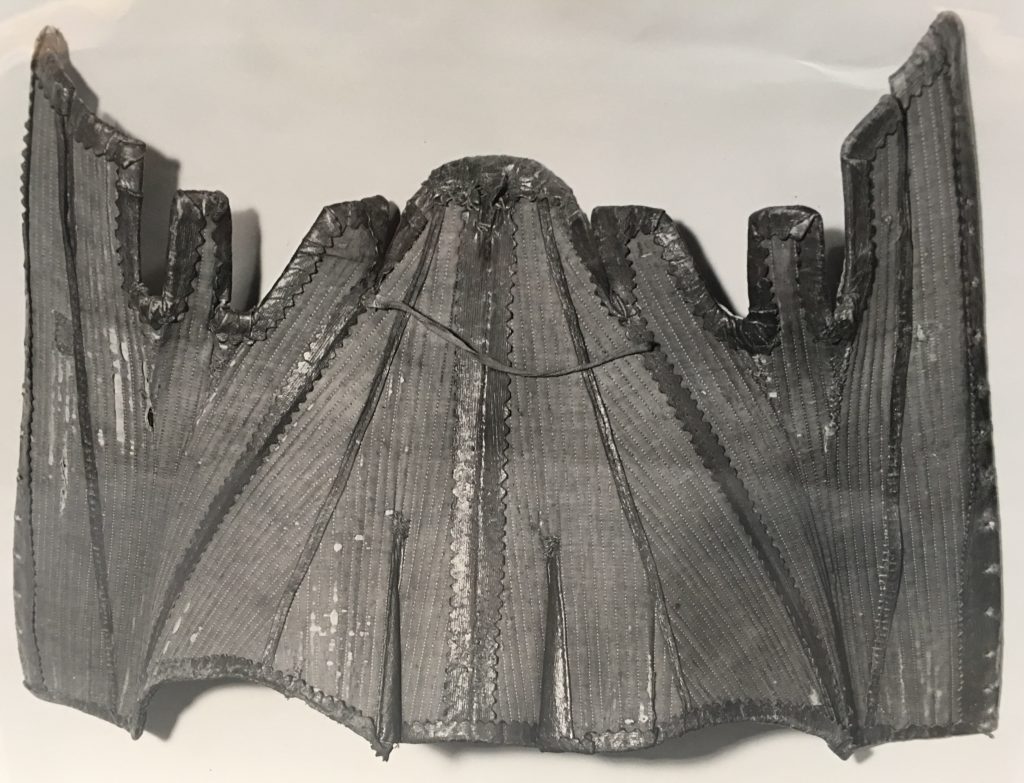

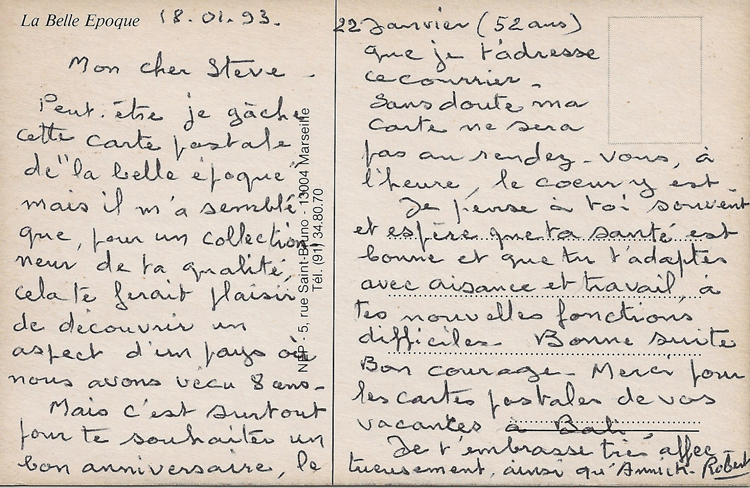

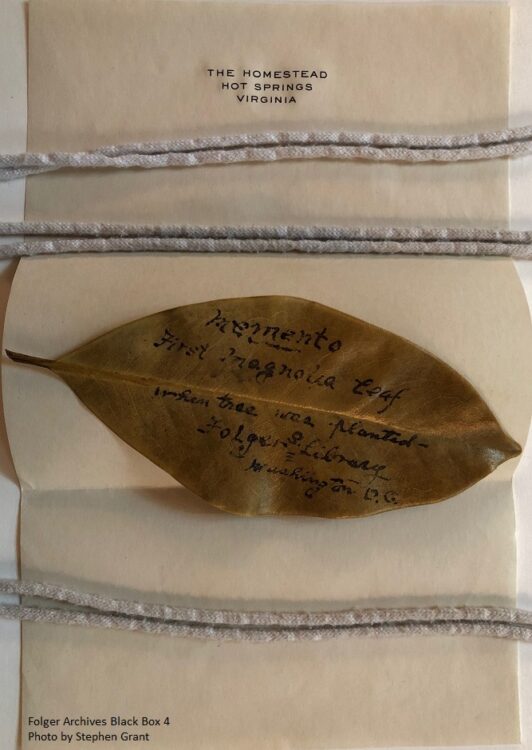

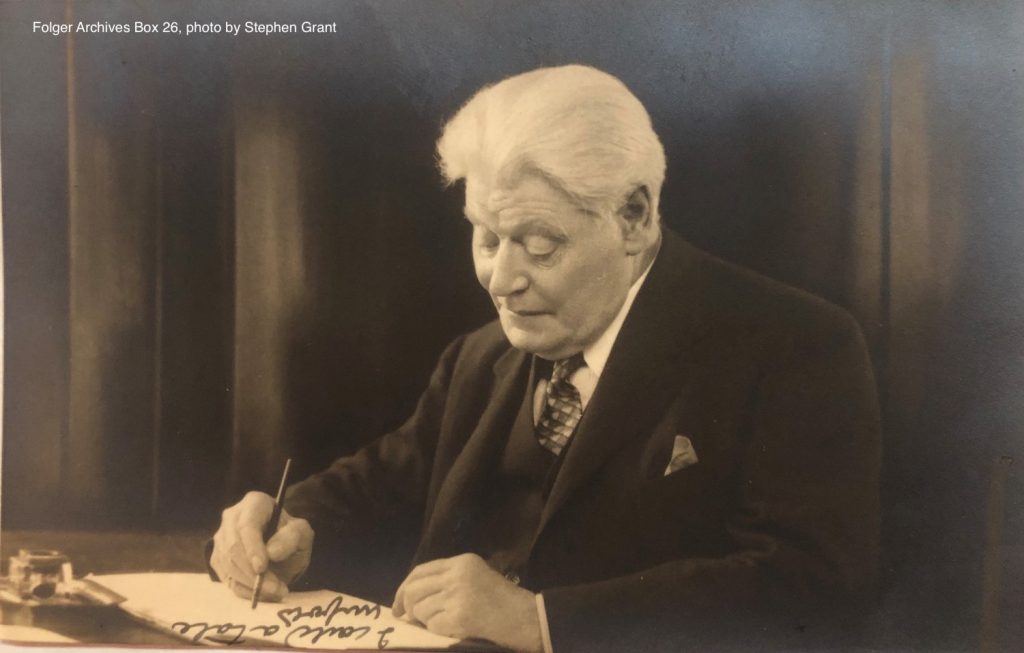

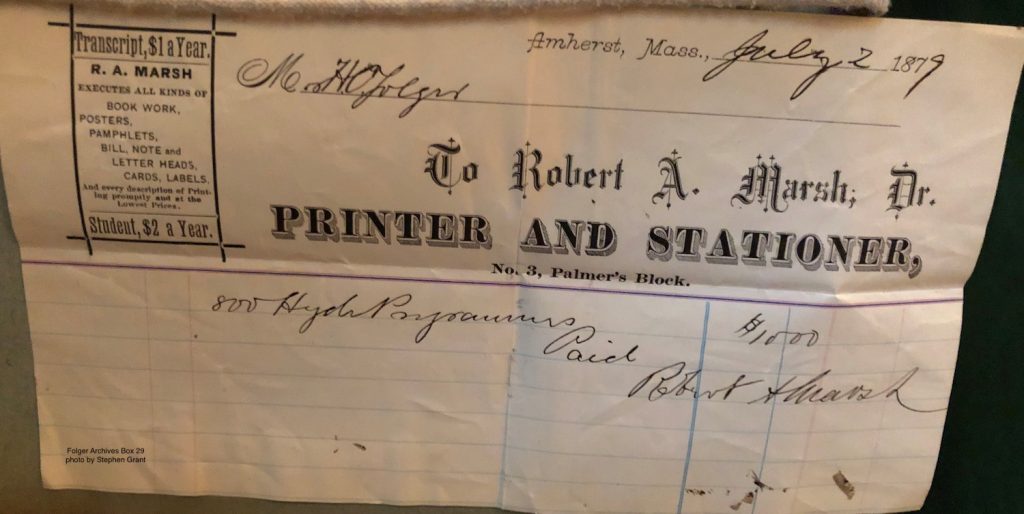

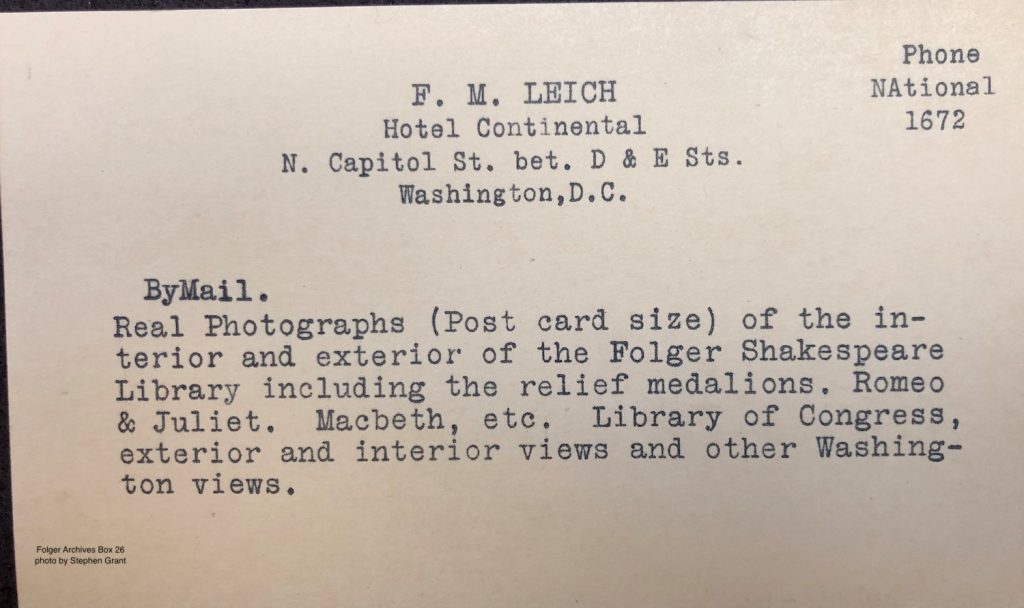

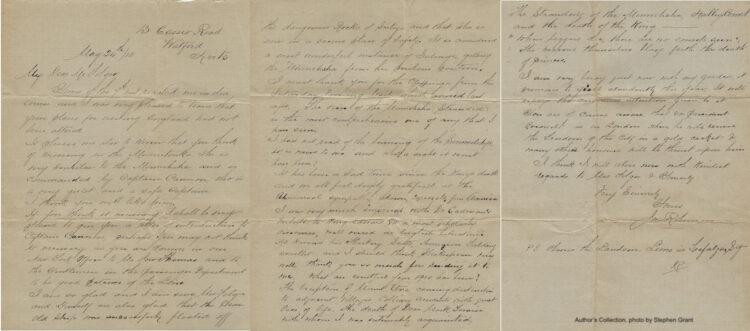

Incoming and outgoing mail was one of the most significant activities for Peter Strickland as he carried out his commercial and consular duties. He commended young Senegalese mechanics for their resourcefulness in making him a postal scale. “Got the blacksmith to mend my little letter balance which got broken by a fall nearly a year ago and he did it so neatly and effectually that the balance is quite as good and looks almost as well as ever. Some of the young mechanics in this country learn their trades very well.” At New Years, Strickland mailed cards to his friends and acquaintances. In 1905, his last year on the island, he sent 150 cards, which saved him “a great deal of time and trouble.” Strickland read and wrote his mail in a “writing cage,” probably as protection from mosquitoes. We have no drawings of it, but its construction in painted wood were assignments he gave to Carlo da Silva, a Cape Verdean he hired to be live-in carpenter, handyman, and storekeeper. Strickland’s Congregational upbringing in Connecticut taught him that writing or reading business correspondence on the weekend would not please the Lord, a practice he faithfully followed. In the same vein, he frowned upon loading or unloading ship cargo on the Sabbath.

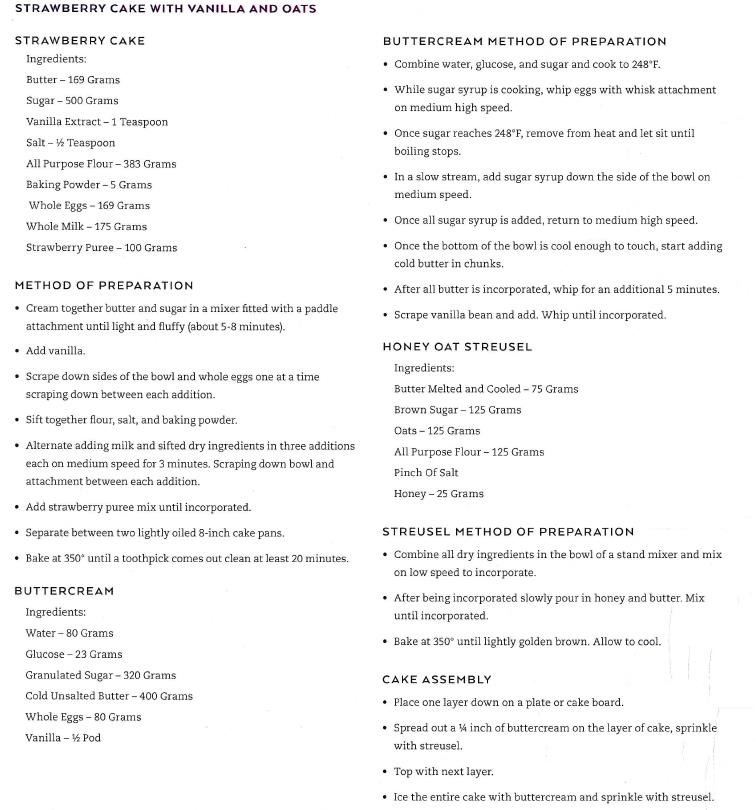

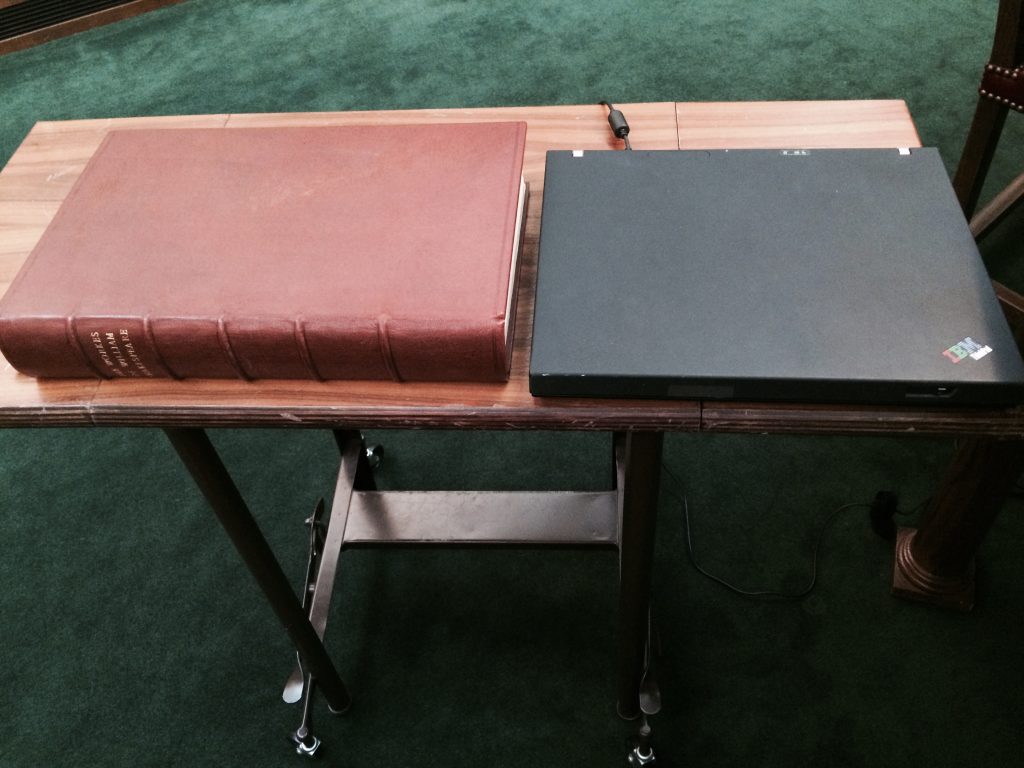

Peter Strickland kept a daily journal for 64 years! First entry, Jan. 1, 1857 at age 19, as he left Boston on a sailing vessel to bring coal and iron to Mexico. His last entry just a century ago in 1921 ended in mid-sentence. To give a flavor, I will share a few diary entries.

5/17/64 Cargo casks of tobacco unloaded in Goree, lumber in Dakar

3/9/66 (from Rufisque) Got off 21 boatloads of peanuts today (nearly 2500 bushels)

4/28/94 Made a trip to Rufisque and met with moderate success in selling and collecting. Returned in the cutter Jeanne, arriving about 4:15 pm after a passage of an hour

5/30/94 Went to Rufisque by train and returned in a lighter, after having sold there more than $300 in goods

1/20/95 Small pox raging badly in Goree and Rufisque

1/21/95 Went to the hospital and got vaccinated

10/6/95 Report of dangerous typhoid fever in Dakar and Rufisque

7/22/08 Wrote and mailed a letter to Maurel Freres of Rufisque

3/21/13 Mailed two small photos which Sika took of me in the act of shoveling snow from the verandah when the branches of the trees were covered with snow to Mr. Escarpit, Mayor of Rufisque, and agent of Maurel Freres in Senegal.

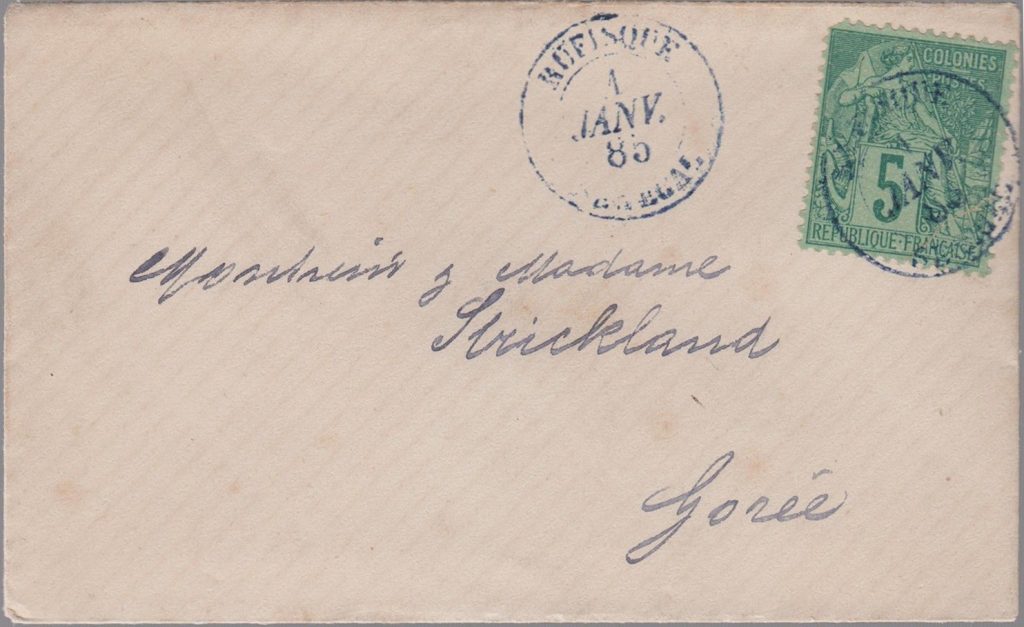

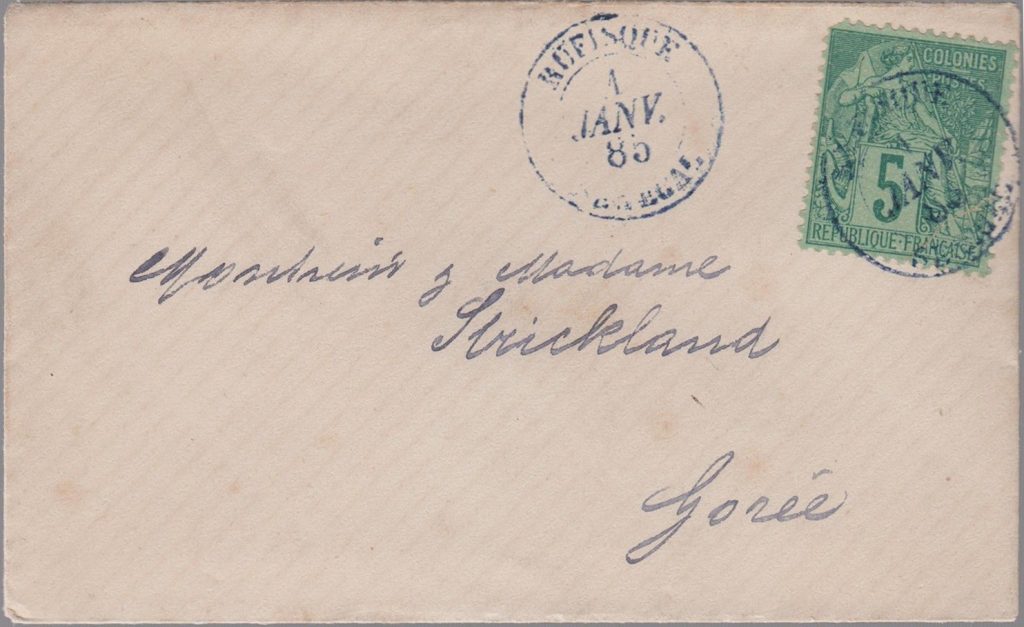

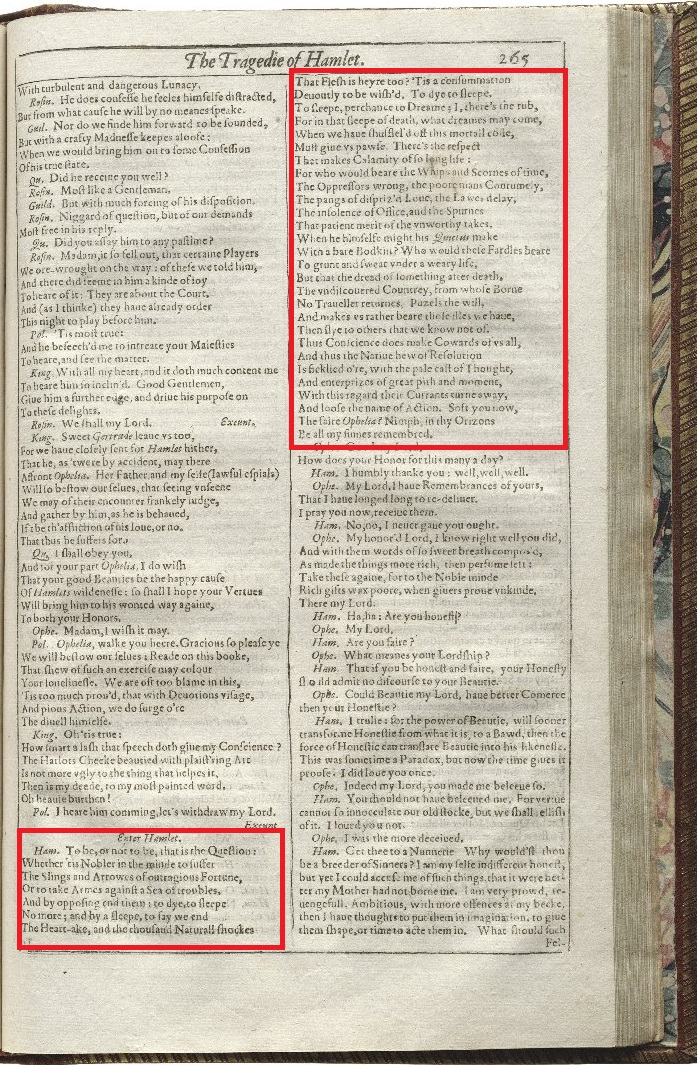

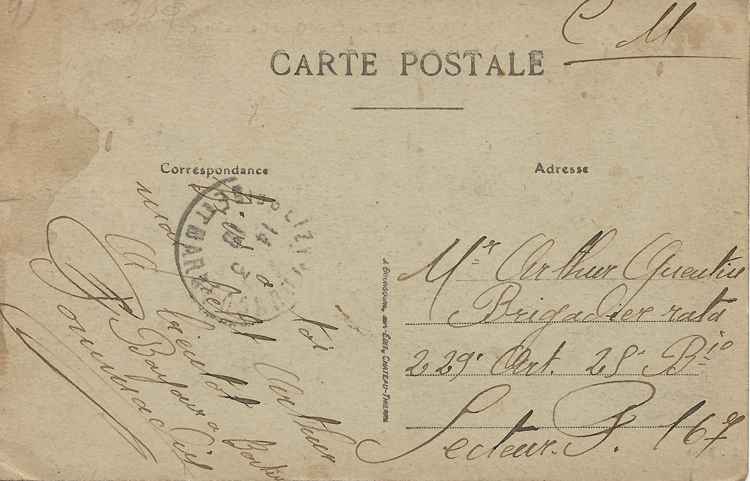

Fig. 3. Cover sent from Rufisque, Sénégal to Monsieur y Madame Strickland, Gorée, 1/1/85

Rufisque is located 13 mi. east of Dakar along the peninsula, opposite Gorée Island. This small cover posted on New Year’s Day in 1885 presents an enigma; Madame Strickland never lived in Gorée. From 1877 to 1880, she did accompany Monsieur to West Africa when he lived in the Portuguese colony of Bissau (now Guinea Bissau), where she was often ill. Daughter Mademoiselle Mary (called Sika) Strickland did live in Gorée during most of Peter’s time there. The correspondent could have been Hispanic, as the “y” was used rather than the French “et.”

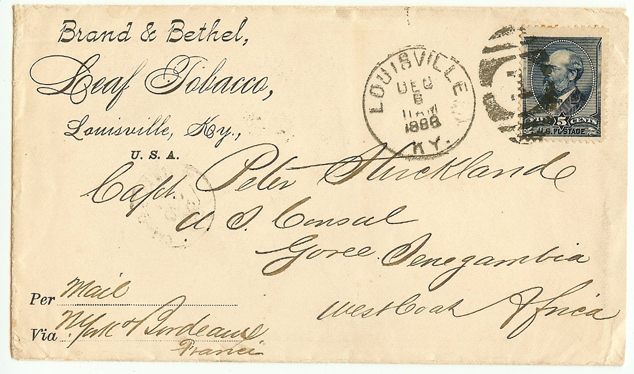

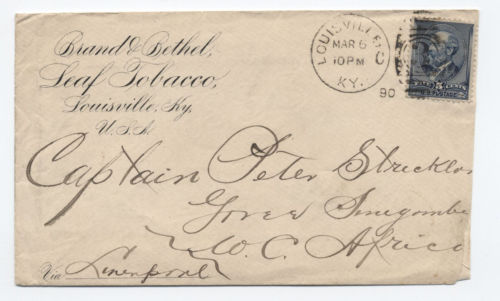

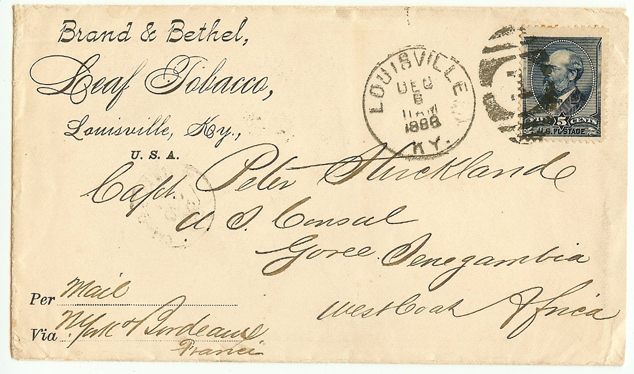

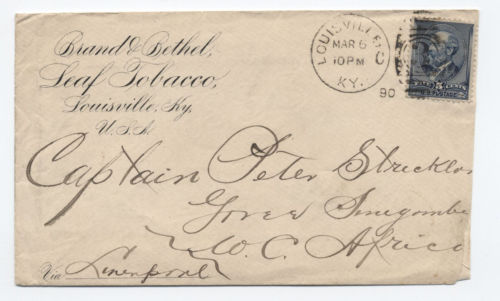

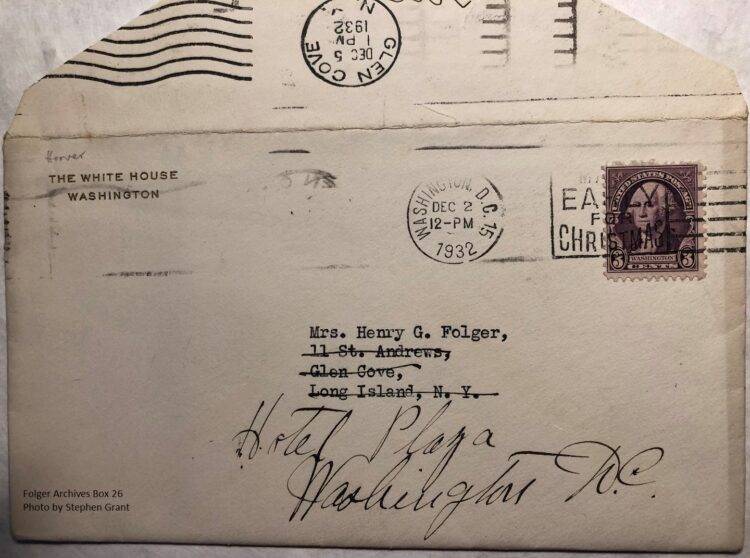

Fig. 4. Cover sent from Brand & Bethel Tobacco Co., Louisville, Kentucky, to Peter Strickland, Gorée, 12/6/88

On 3/14/90, Strickland wrote letter no. 77 to Brand & Bethel Leaf Tobacco Company in Louisville, Kentucky with this information: Senegambia is thought to contain nine millions of inhabitants, the coast about 500 miles in extent is in the hands of Europeans. Up to 1865 little tobacco was used in this country but now the yearly consumption is nearly 5000/2 hhds. Traders penetrate farther into the interior continually and new avenues for its consumption are being opened up.

For maritime shipment, tobacco was packed tightly in wooden barrels, 48 in. long and 30. In in diameter, that could weigh 1,000 lbs. The unit of measure is a tobacco hogshead (hhd). “Senegambia” refers to the French colony of Senegal and the small (fewer than 4,400 sq. mi.) The British colony of The Gambia has a coastline and separates Senegal in two. I posit that Peter Strickland bears an important role in habituating both French and indigenous populations in West Africa to feel a need for the weed.

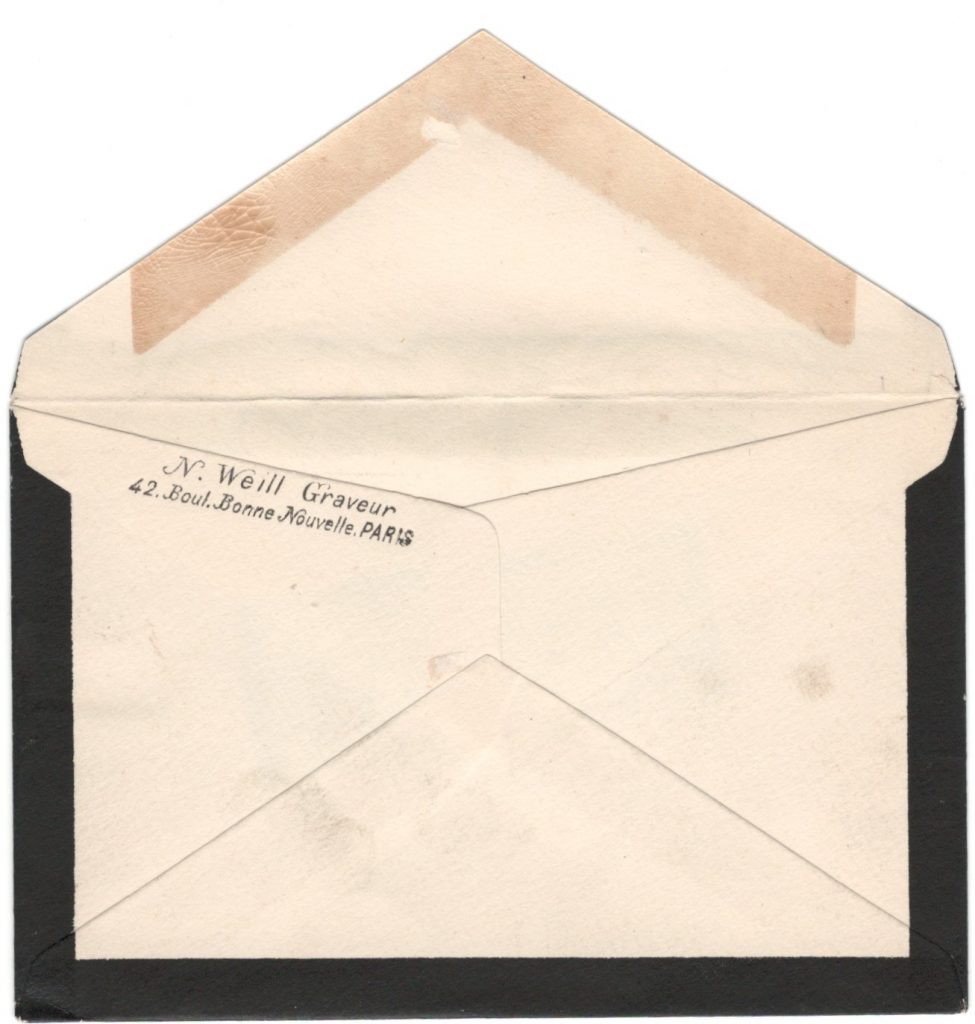

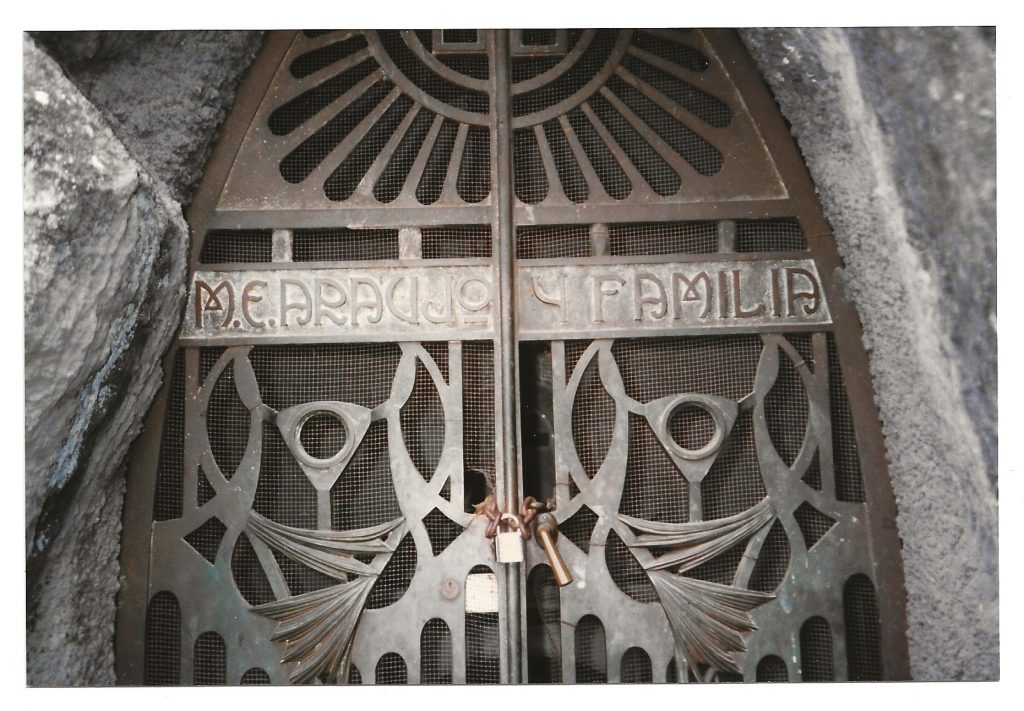

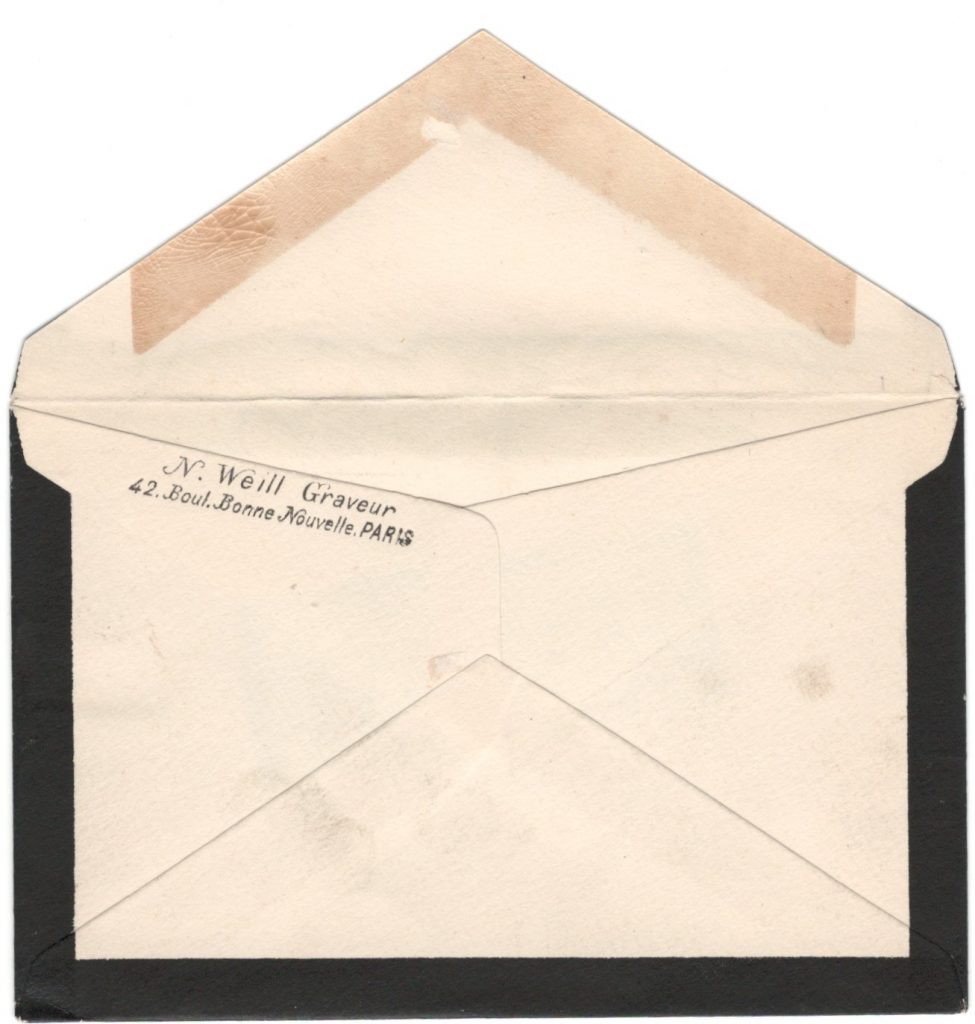

Fig. 5. Mourning cover from Rufisque to P. Strickland y familli, Gorée, 12/31/88

Fig.6. Mourning cover (back) arrived in Gorée, 12/31/88

This mourning cover was written in the same handwriting as in Fig. 3. It is the same five-centime green stamp for use in French colonies. One can assume that the sending post office was also in Rufisque. Most of the letters of the sending town are hidden by the wide black mourning band around the envelope. I can distinguish an “R” as the first letter of the sending P.O. Unfortunately, return addresses were rarely included on personal correspondence in this period. Fortunately, most commercial establishments printed their addresses on the front side of envelopes. Mourning envelopes were more expensive than a normal envelope; especially one identified as the work of a well-known printer and engraver like N. Weill of 42 Blvd Bonne Nouvelle, Paris.

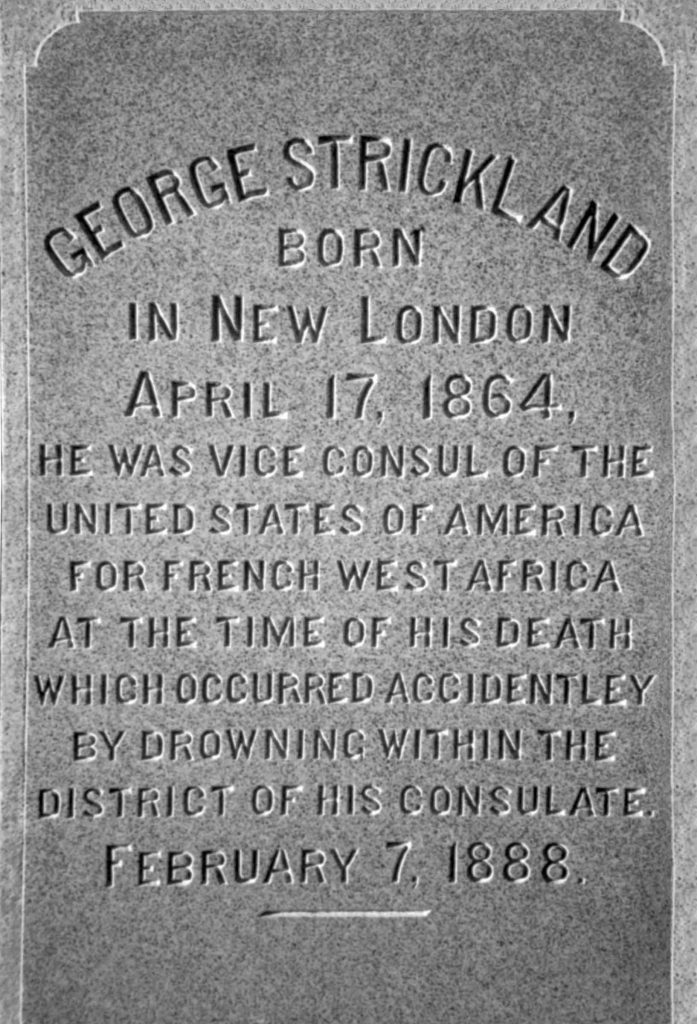

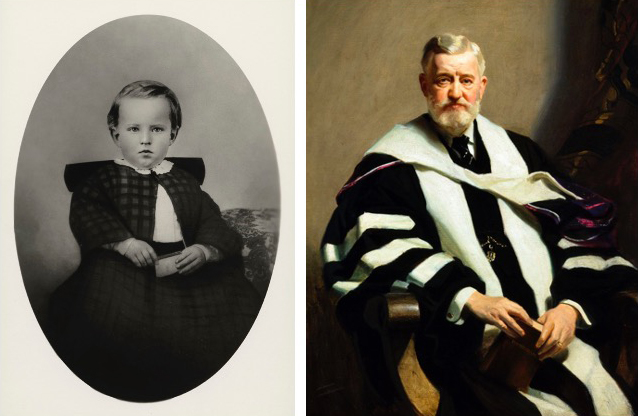

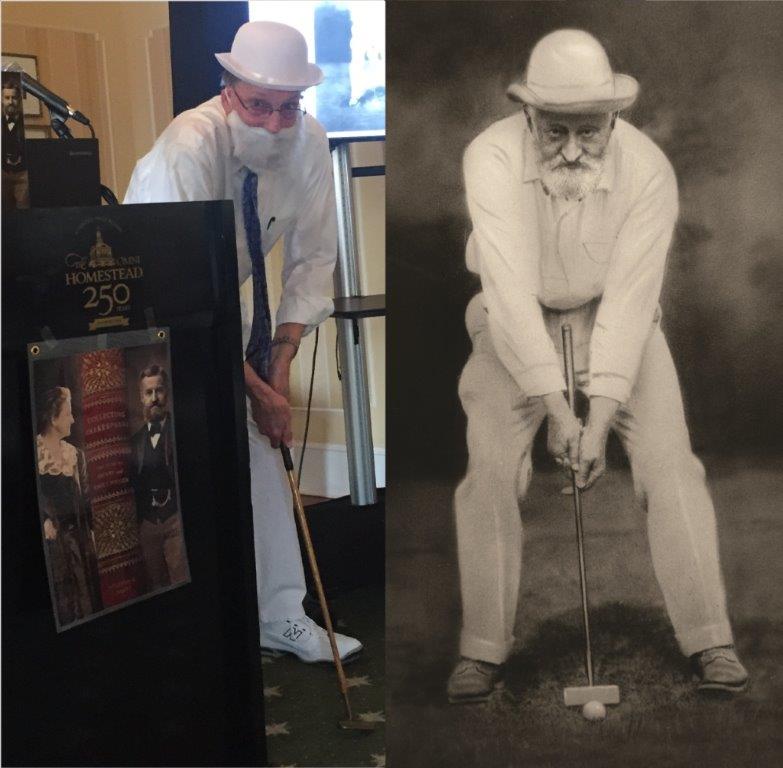

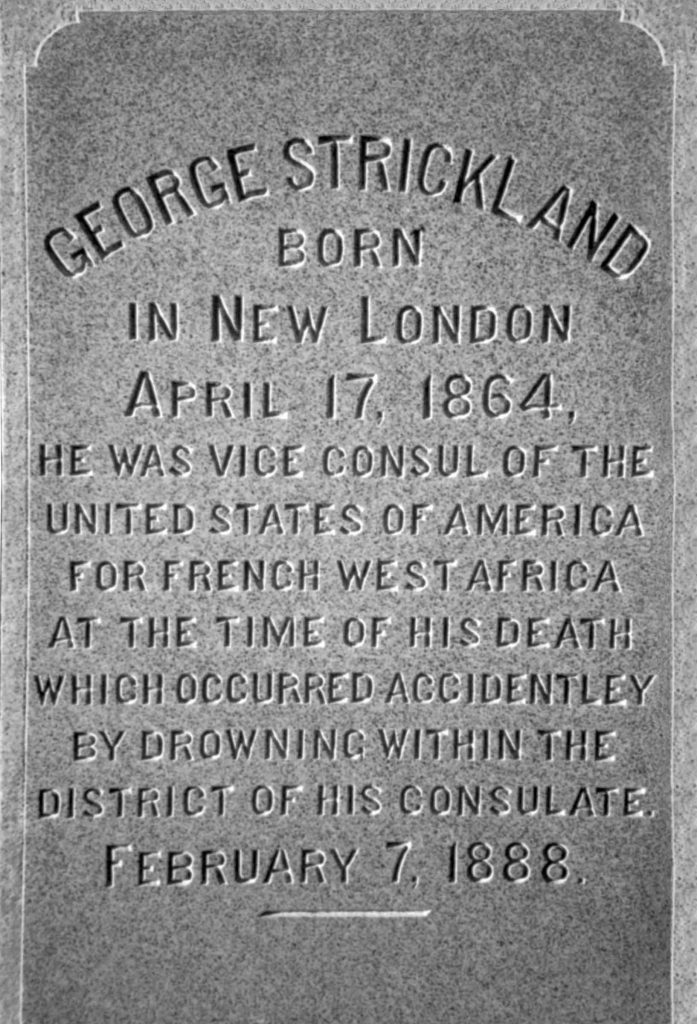

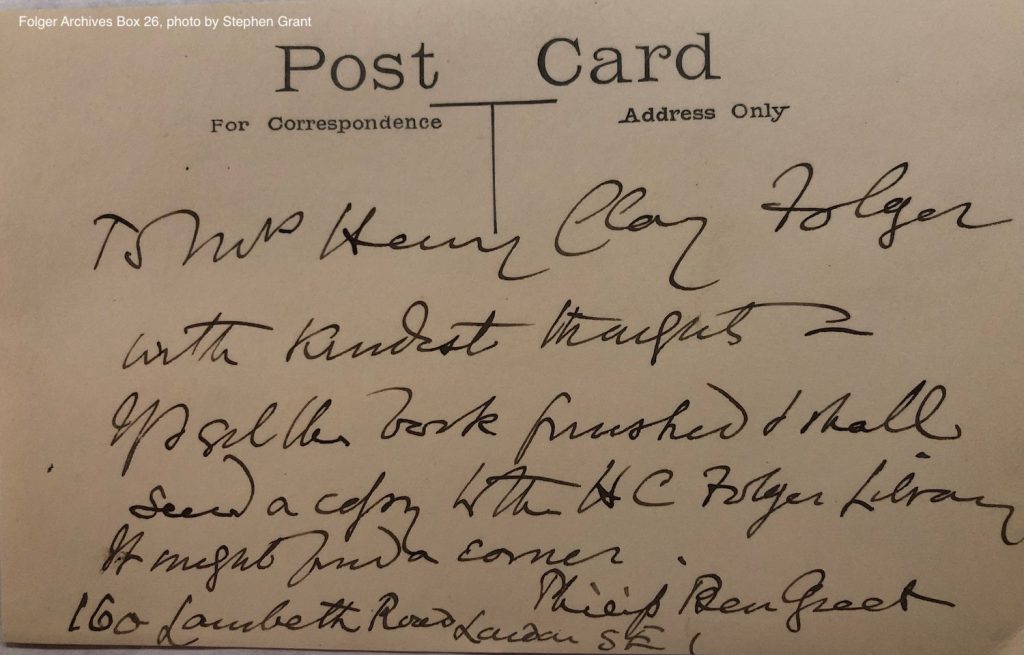

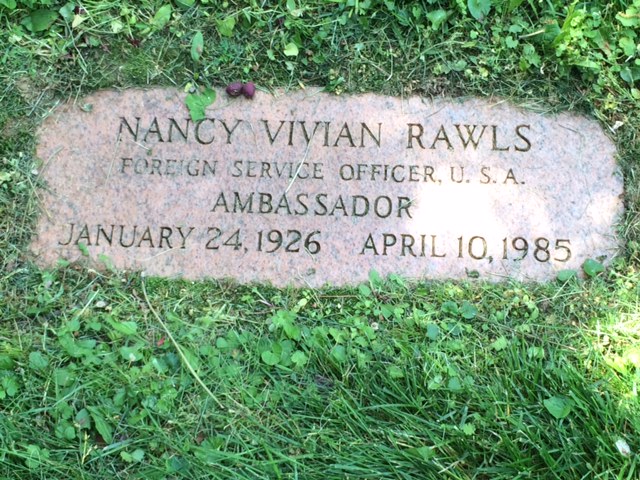

For the biographer of Peter Strickland, it is no secret whose death is being mourned in Figs. 5–6. Here is my photograph of the gravestone:

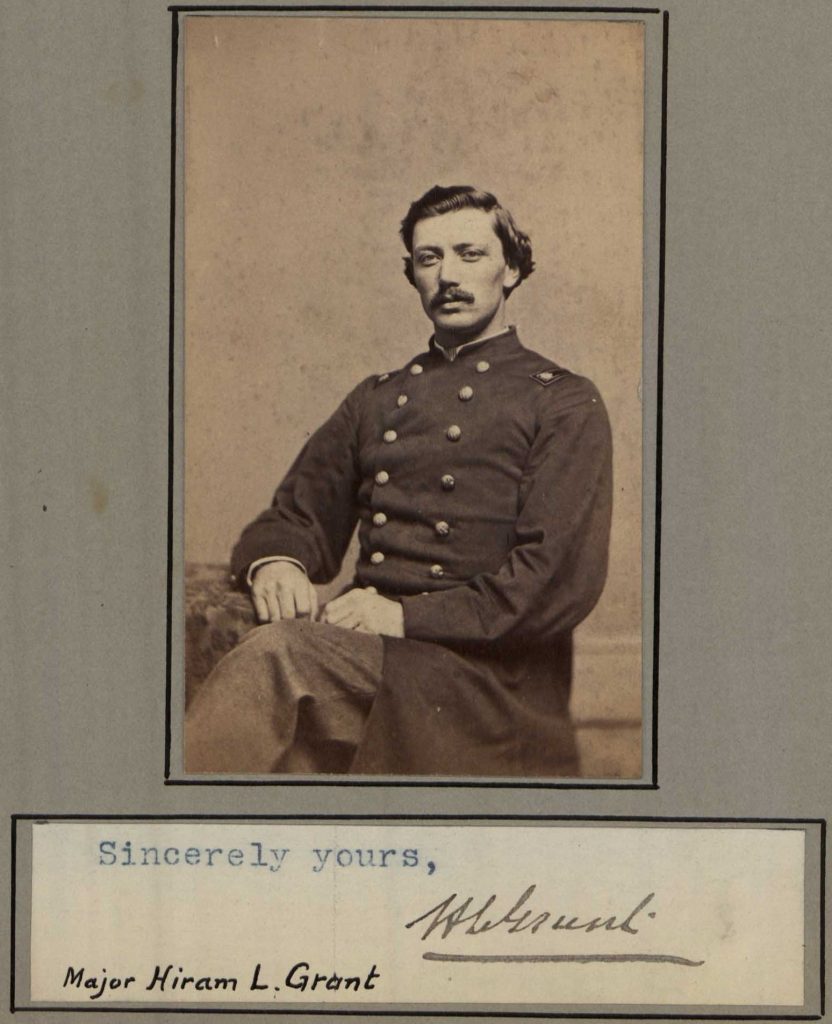

Fig. 7. George Strickland gravestone, Cedar Grove Cemetery,

New London, Conn. Photo by Stephen Grant

GEORGE STRICKLAND BORN APRIL 17, 1864 NEW LONDON. HE WAS VICE CONSUL OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FOR FRENCH WEST AFRICA AT THE TIME OF HIS DEATH WHICH OCCURRED ACCIDENTALLY BY DROWNING WITHIN THE DISTRICT OF THE CONSULATE FEBRUARY 7, 1888

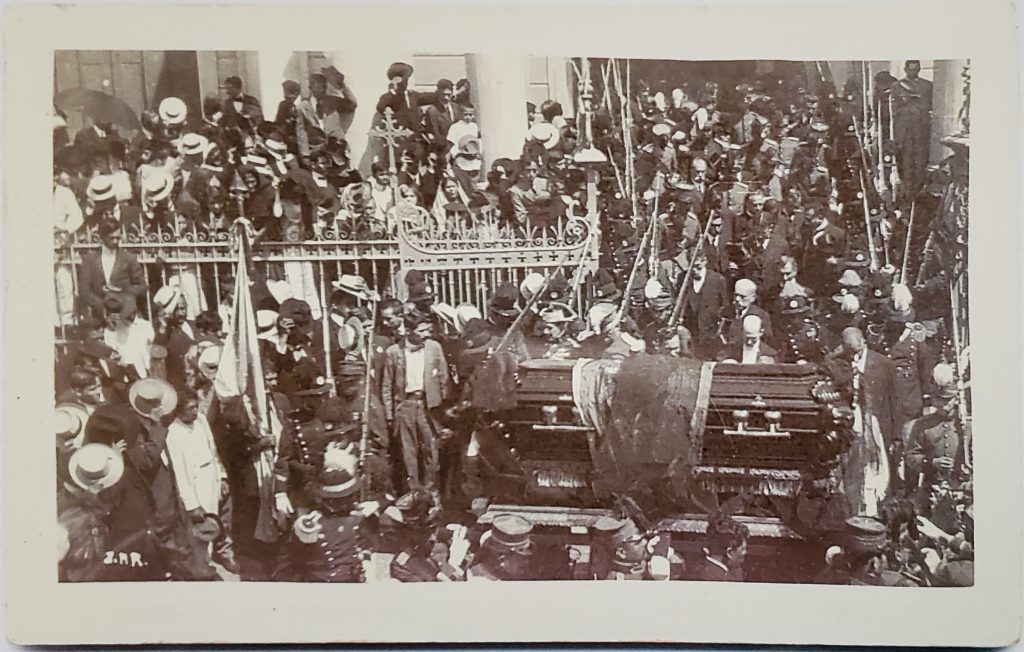

Son George Strickland died in mysterious circumstances. Here is how the pained father reported the event in his Consular Dispatch No. 83 to the State Department on 2/20/ 88:

I have the extreme unhappiness to inform you of the death

by drowning on the evening of the 7th instant of my only

Son, Mr. George Strickland, the Vice-Consul. He embarked

for Saint-Louis taking passage in the Schooner M. E.

Higgins, on the morning of the 6th instant, and when the

vessel was about fifteen miles NW of Cape de Verde Light

he accidentally fell from one of the rails where he was sitting

without apprehension of danger into the sea. A boat was

launched instantly and every effort made to save him but

he sank finally before he could be picked up. It was about

eight o’clock in the evening when the accident occurred.

The vessel was kept as near as possible to the spot all of that

night and the most of the next day when, finding no trace of

anything she returned to Goree with the sad news.

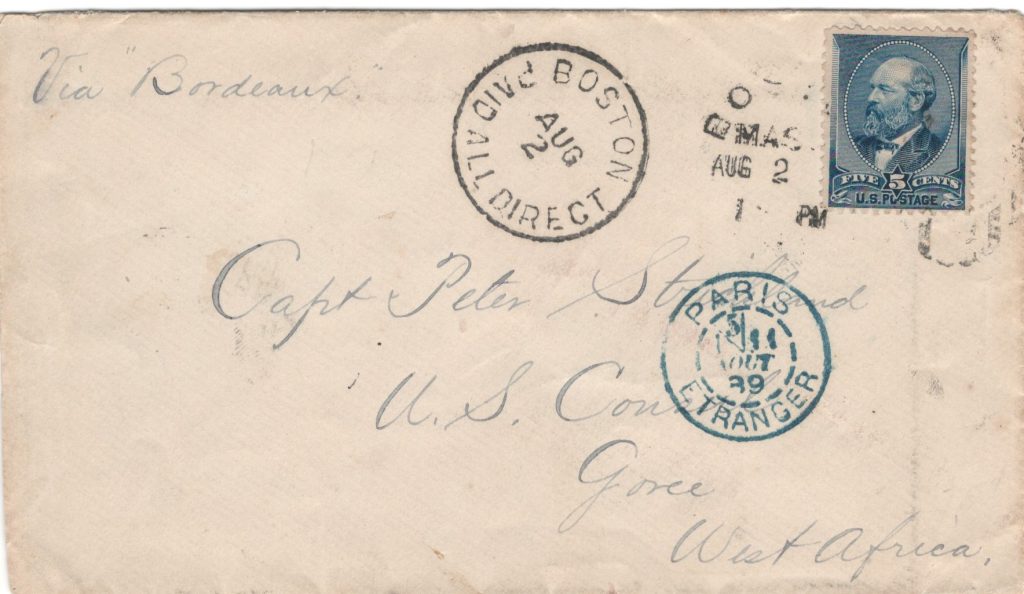

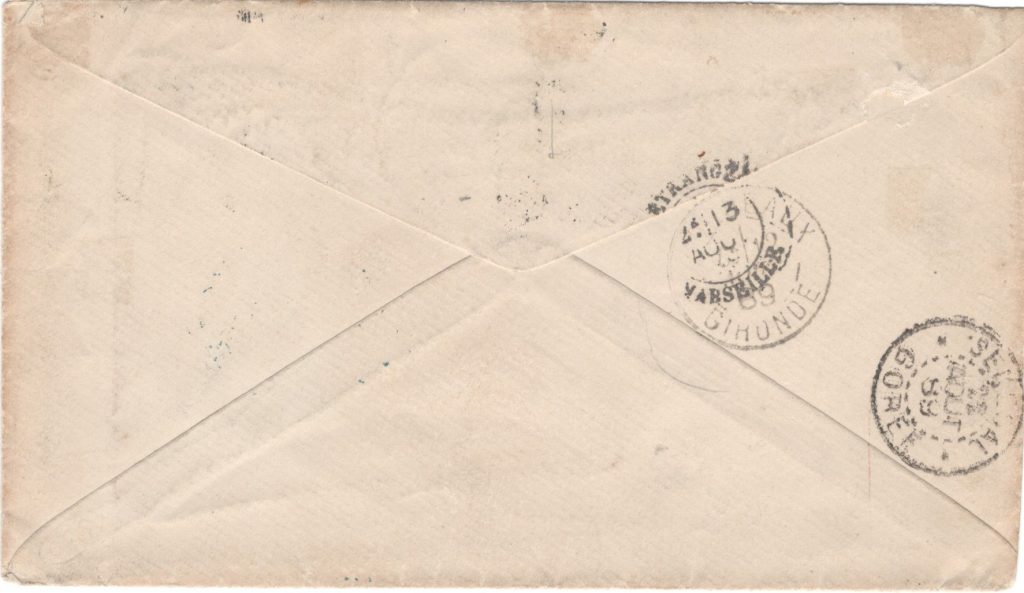

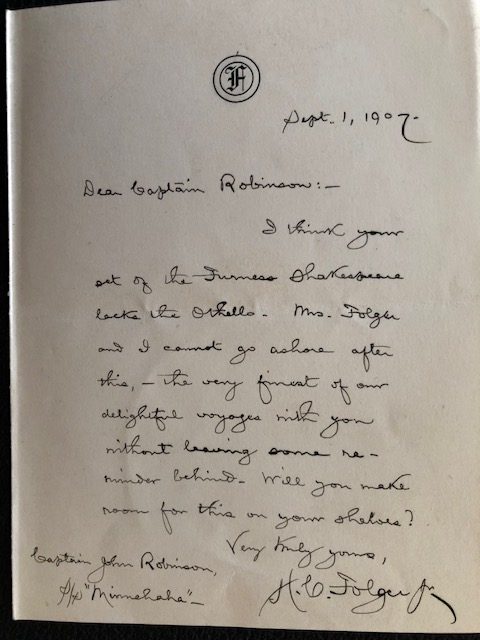

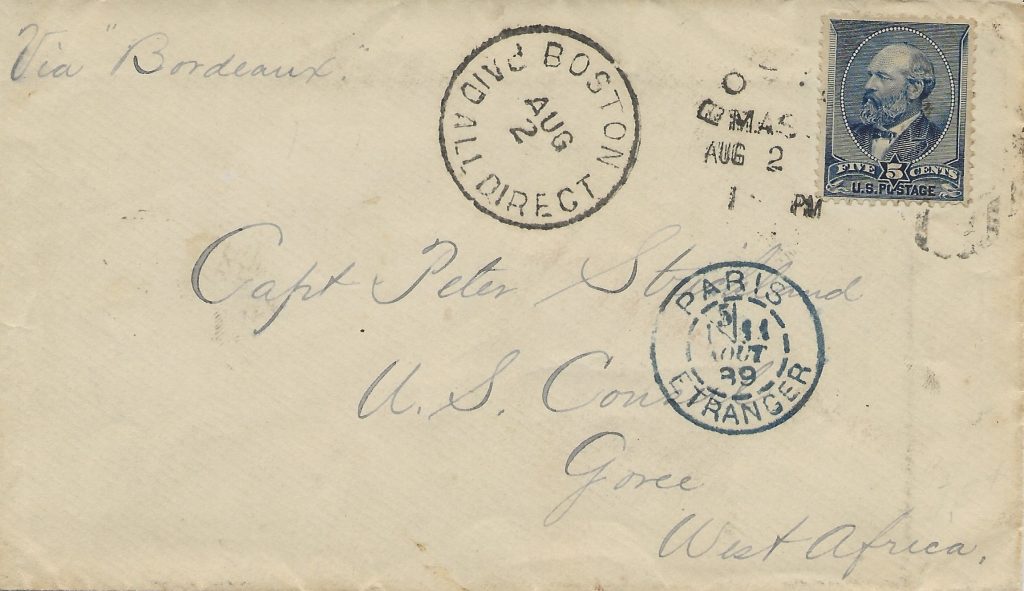

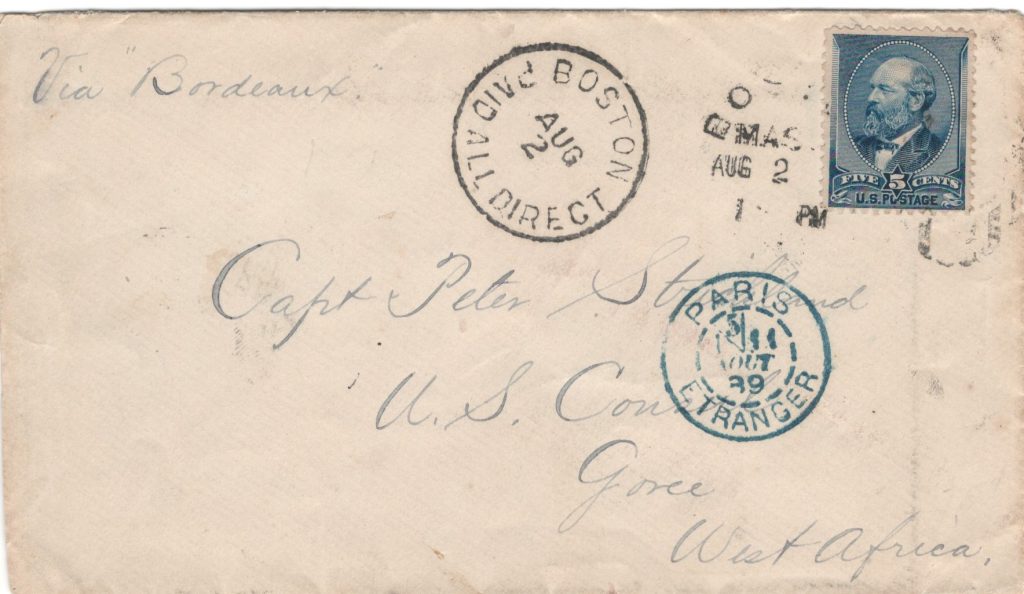

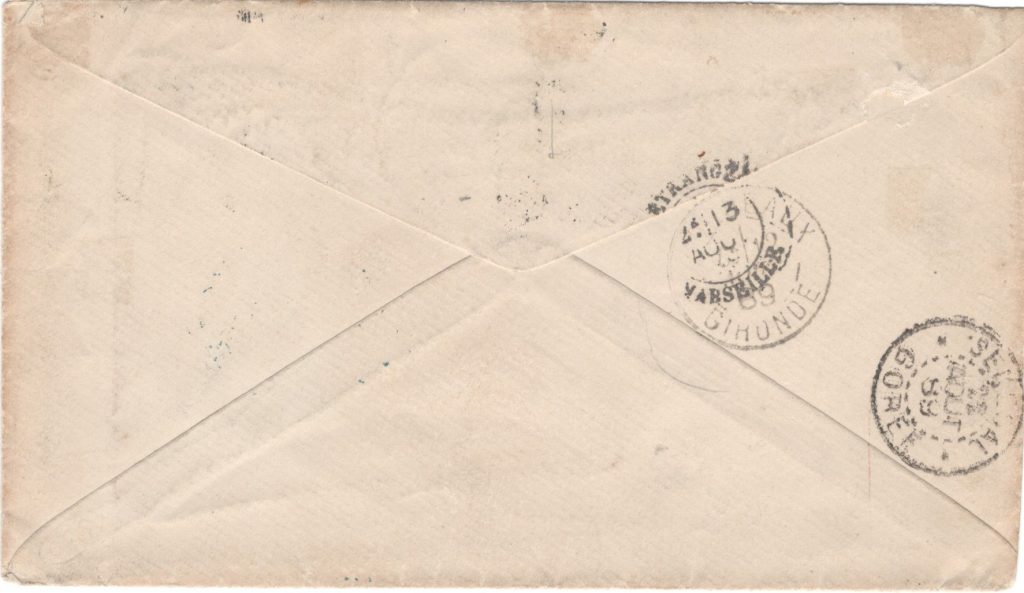

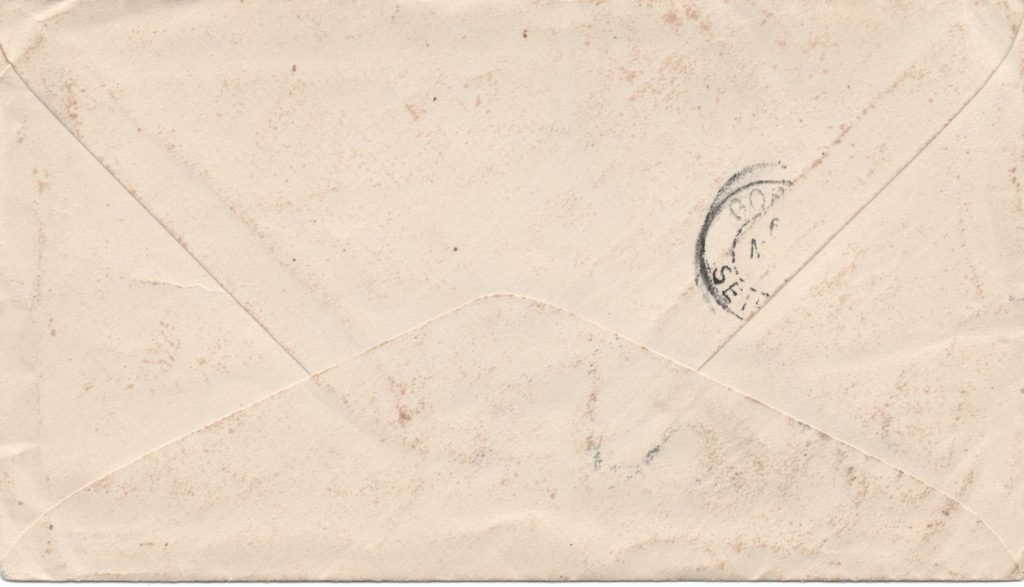

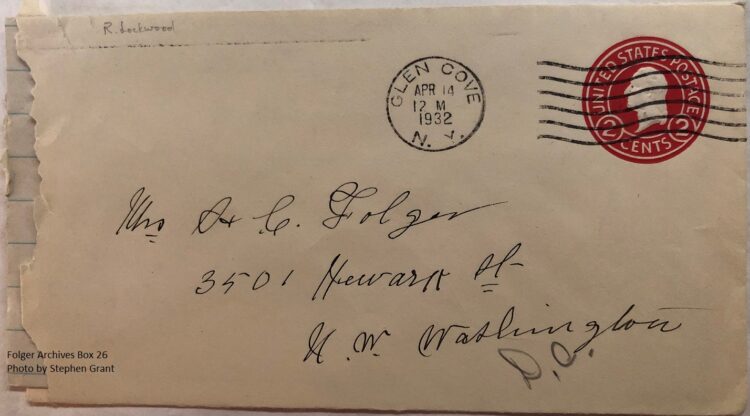

Fig. 8. Cover sent from Boston to Peter Strickland in Gorée, 8/2/89

Fig. 9. Cover (back) arrived in Gorée, 8/2/ 89

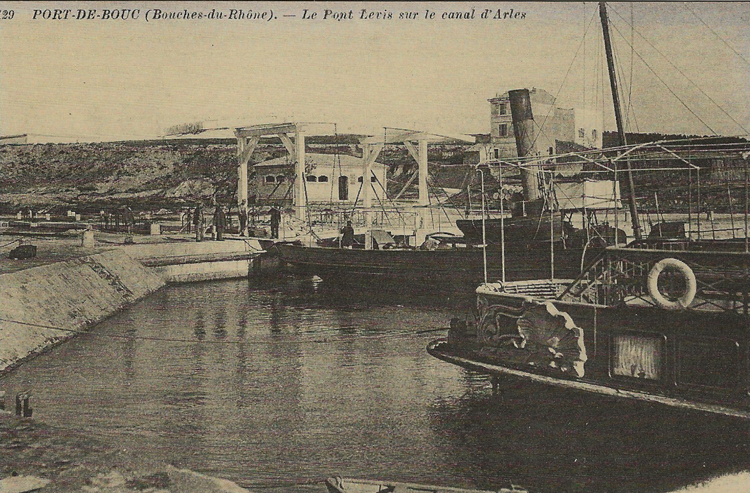

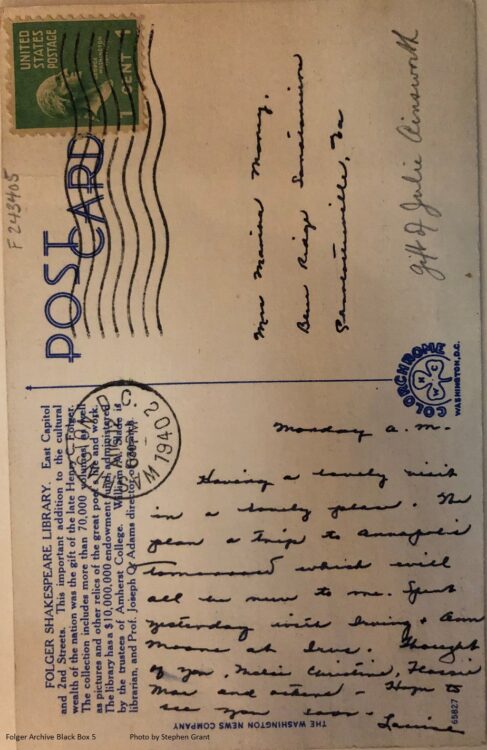

It is interesting to follow the five postmarks on the above piece of mail sent 8/2/89 from my birth city, Boston, to Gorée, with intermediate stops at Paris 8/11, Bordeaux 8/12, and Marseilles 8/13, before reaching its destination on 8/22. That’s three weeks; sometimes mail takes as long today.

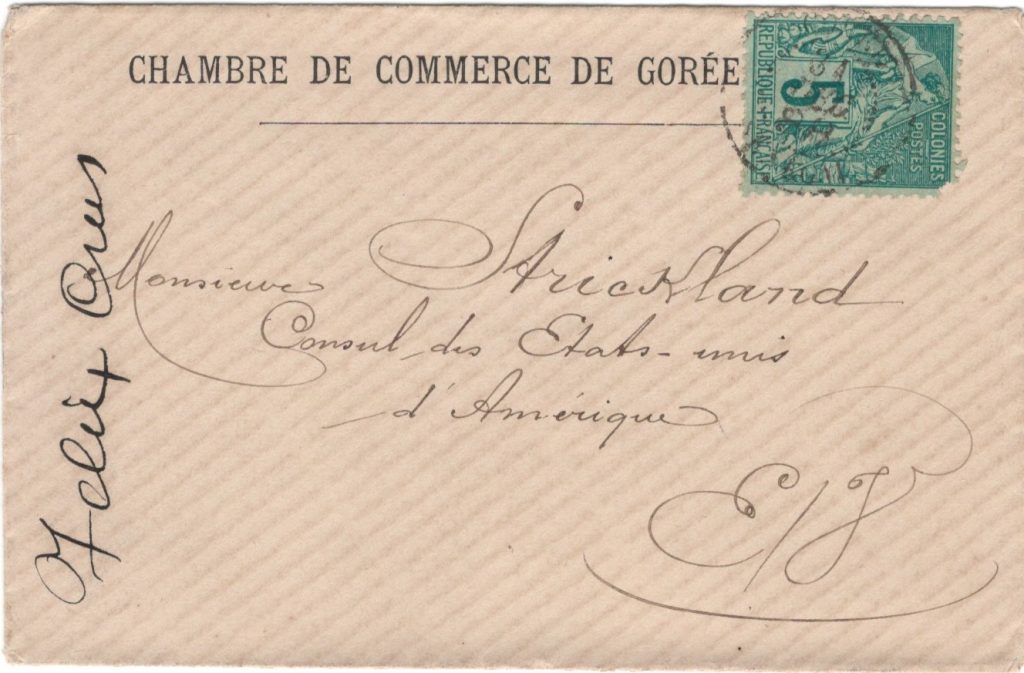

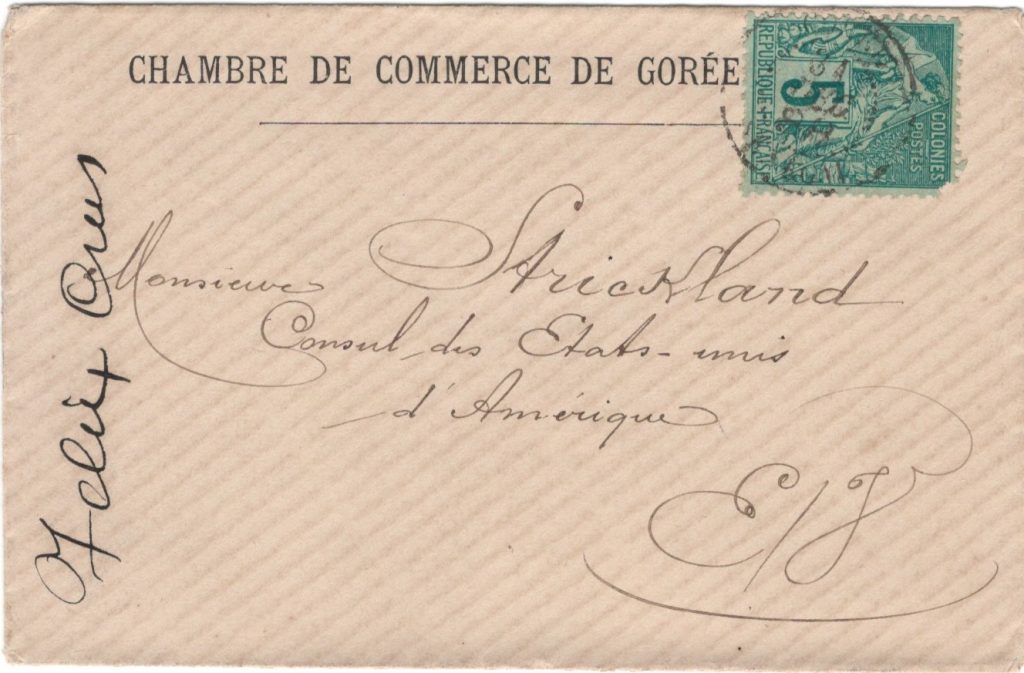

Fig. 10. Cover sent from Gorée to Peter Strickland in Gorée, 12/31/88

Felix Crus must have worked at the Chamber of Commerce in Gorée. On 4/15/00, Peter Strickland wrote a letter in French to a M. Crus. “E/J” stands for enveloppe jointe, a note for the postal clerks to treat the official mail with care. The envelope mailed on the last day of Peter’s annus horribilis might well have conveyed a Happy New Year message. The president of the Gorée Chamber of Commerce was Claude Potin. A letter posted from the Chamber of Commerce to the American consul on Gorée sounds normal and appropriate, doesn’t it? What most readers don’t know is that Strickland and Potin lived across the street from each other, on the rue de Hesse on Gorée. The building Strickland lived in and used for his consulate (see Fig. 29) has been called “la maison Strickland.” Across the street lived Claude Potin, president of the Gorée chamber of commerce in a house now referred to as “la maison dite de l’Aga Khan.

Admire the calligraphy on this cover, and on others.

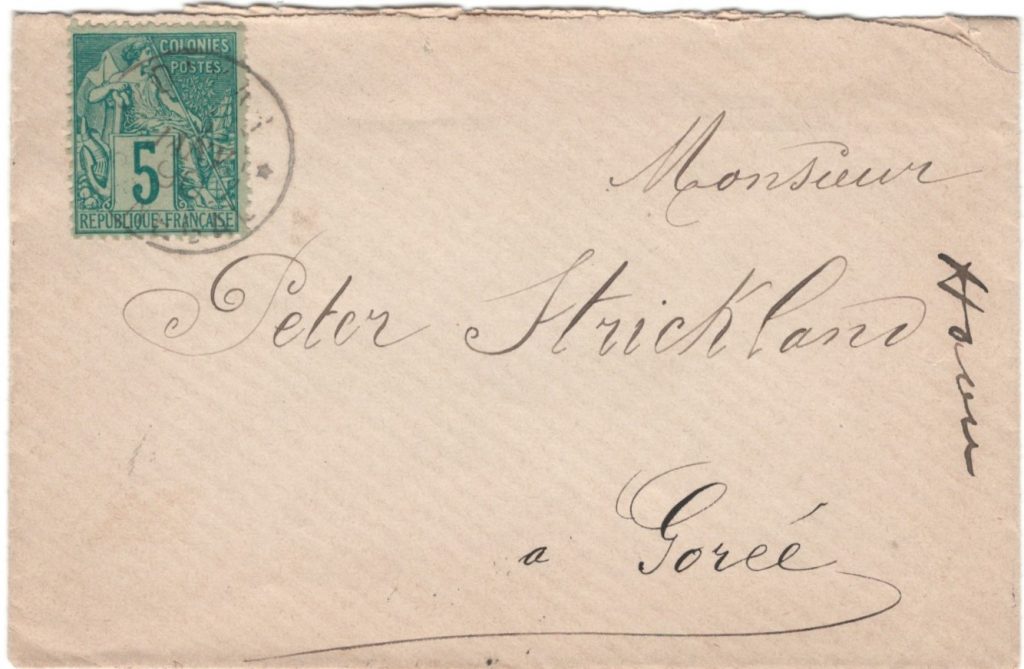

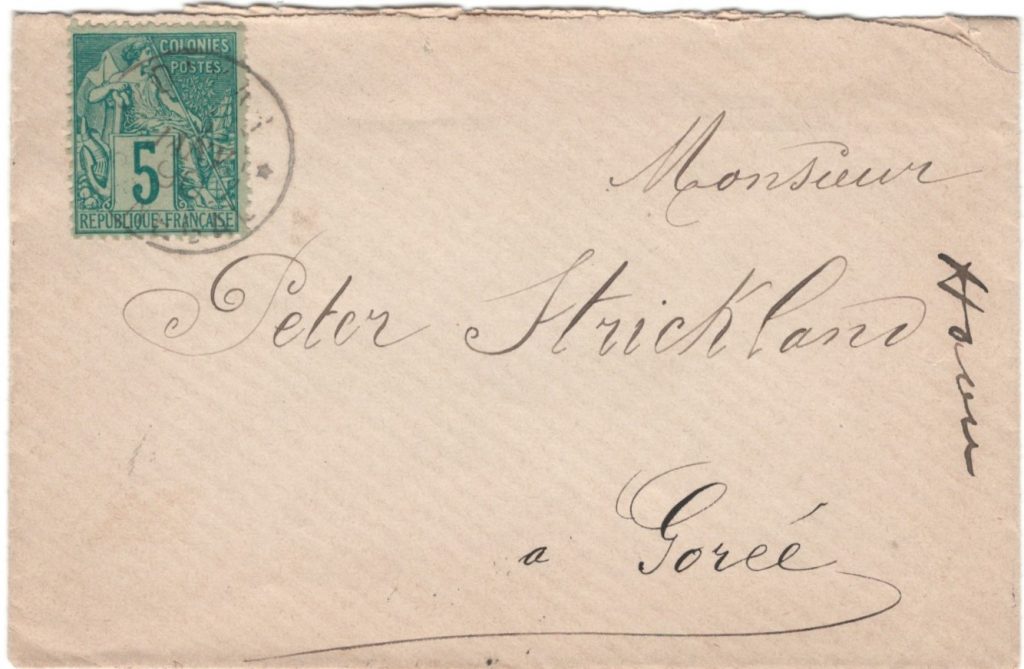

Fig.11. Cover sent from Dakar to Monsieur Peter Strickland, Gorée, 1/3/90

Fig. 11. is the second cover from the Kentucky-based tobacco company, Brand & Bethel. Note that the firm has slightly modified its pre-printed envelope, continuing to print “via,” but eliminating “per.” The reason the “via” prompt was included was that American postal clerks had only an approximate knowledge of West African geography, and often sent mail far afield. “W.C.” stands for West Coast.

Fig. 12. Cover sent from Brand & Bethel Leaf Tobacco, Louisville, Kentucky to Capt. Peter Strickland, Gorée, Senegambia W.C. Africa, 3/6/90

Fig. 13. Cover sent to Monsieur P. Strickland, négociant, Gorée, 12/30/93

Fig. 12. is all business; no consular title is used. We’ve seen postage stamps affixed in the upper right, upper left, now lower left. The Universal Postal Union is responsible for establishing such norms. Founded in 1874, UPU’s precepts had not reached all corners of the earth.

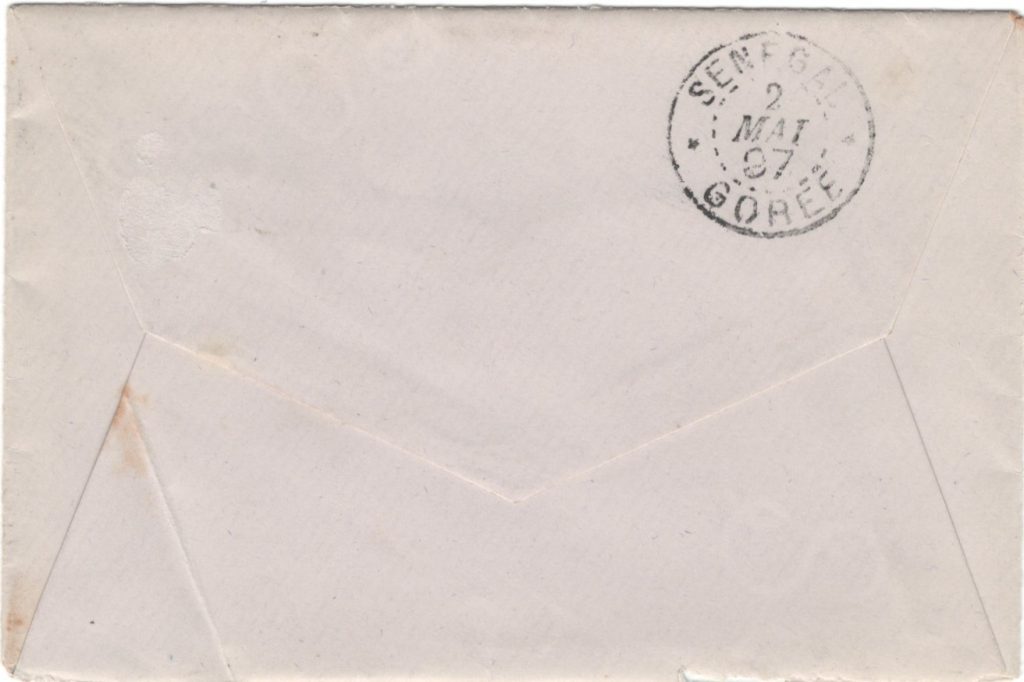

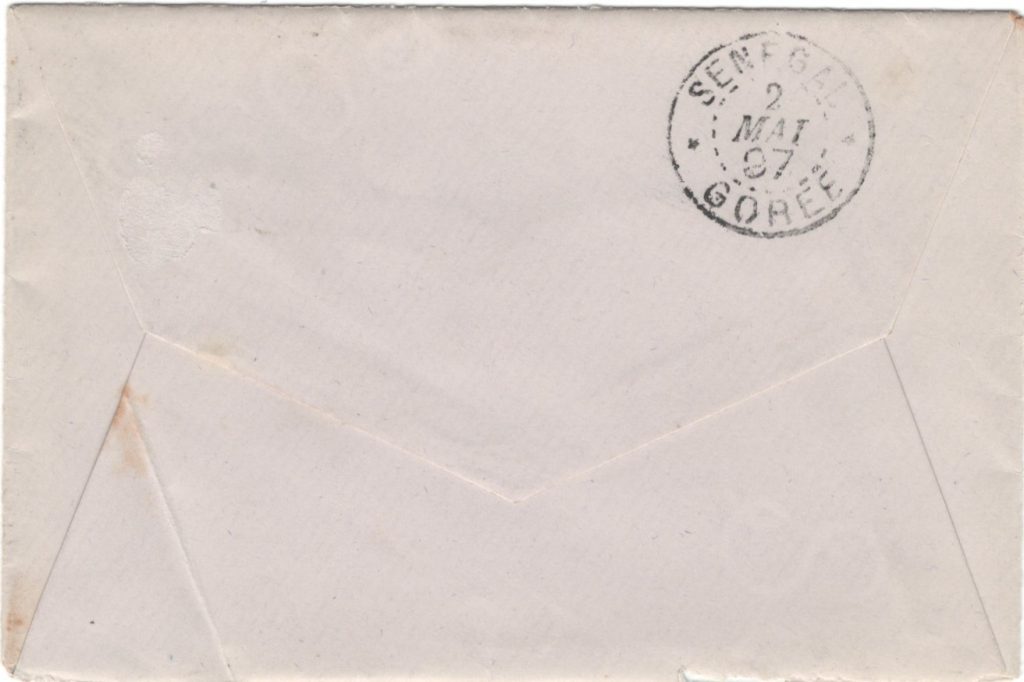

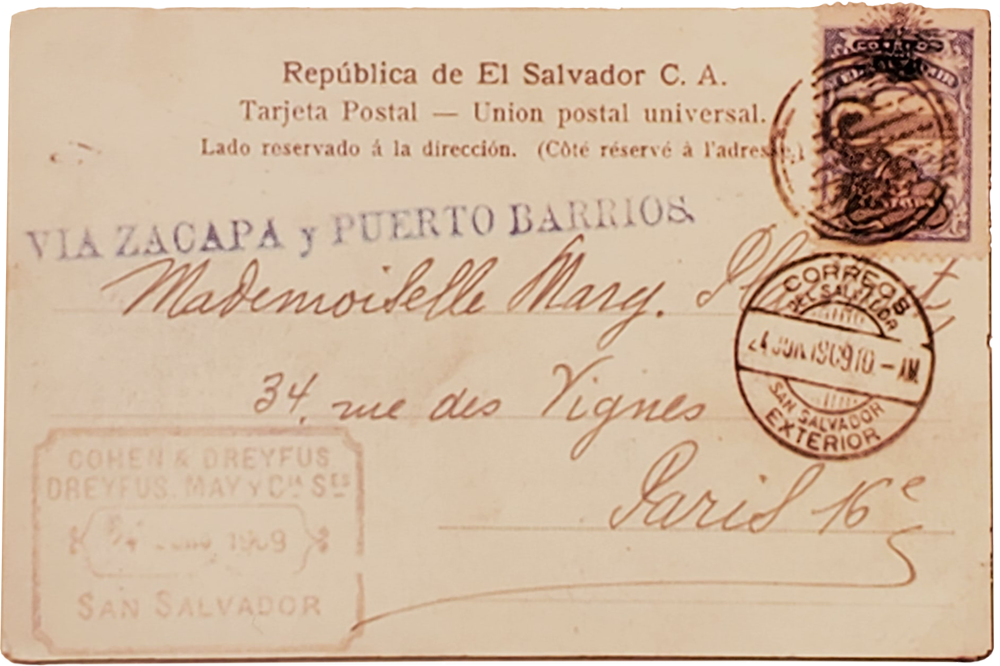

Fig. 14. Cover sent from St. Louis, Senegal to Mademoiselle M. Strickland, Consulat Américain, Gorée, Sénégal, 5/1/97

Fig. 15. Cover (back) arrived in Gorée, 5/2/97

Saint-Louis was the capital of the French colony Senegal from 1673 to 1902, when Dakar became the capital.

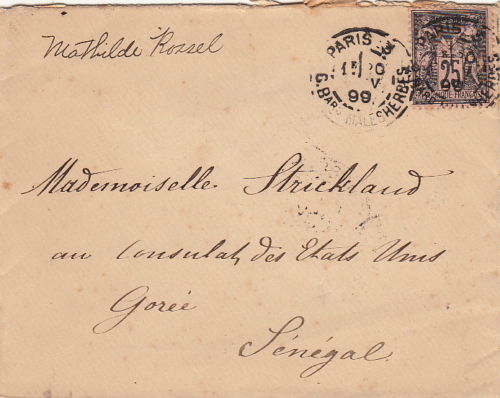

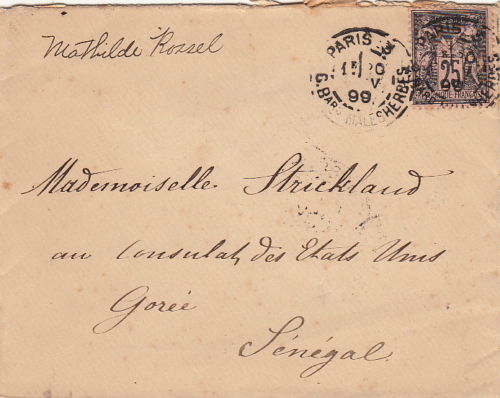

Fig. 16. Cover sent from Paris to Mademoiselle Strickland, 1/20/99 Consulat des Etats-Unis, Gorée, Sénégal. 1/20/99

Fig. 17. Cover (back) arrived in Gorée via Bordeaux, 2/4/99

The cover in Figs. 15–16 made an intermediate stop in Bordeaux on 1/21/99. I assume Mathilde Rossel was Mary’s friend who wrote a letter to her and also that Mathilde’s name is written in Mary’s handwriting. Mary Strickland was born in 1868. She would have accompanied her father to live on Gorée at the age of 12 until the age of 37. In 1945, she died at the age of 77 in her father’s hone in Dorchester, Mass. Her sister Grace had died there in 1906 at the age of 31. Neither daughter married. The line died out.

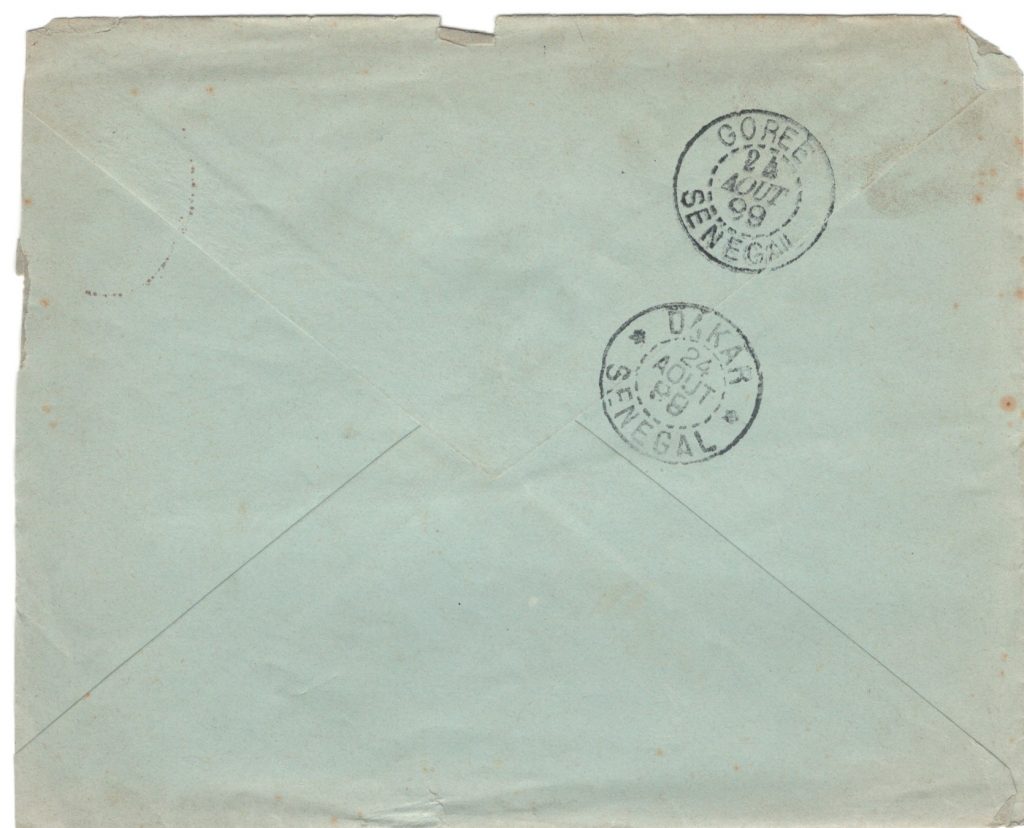

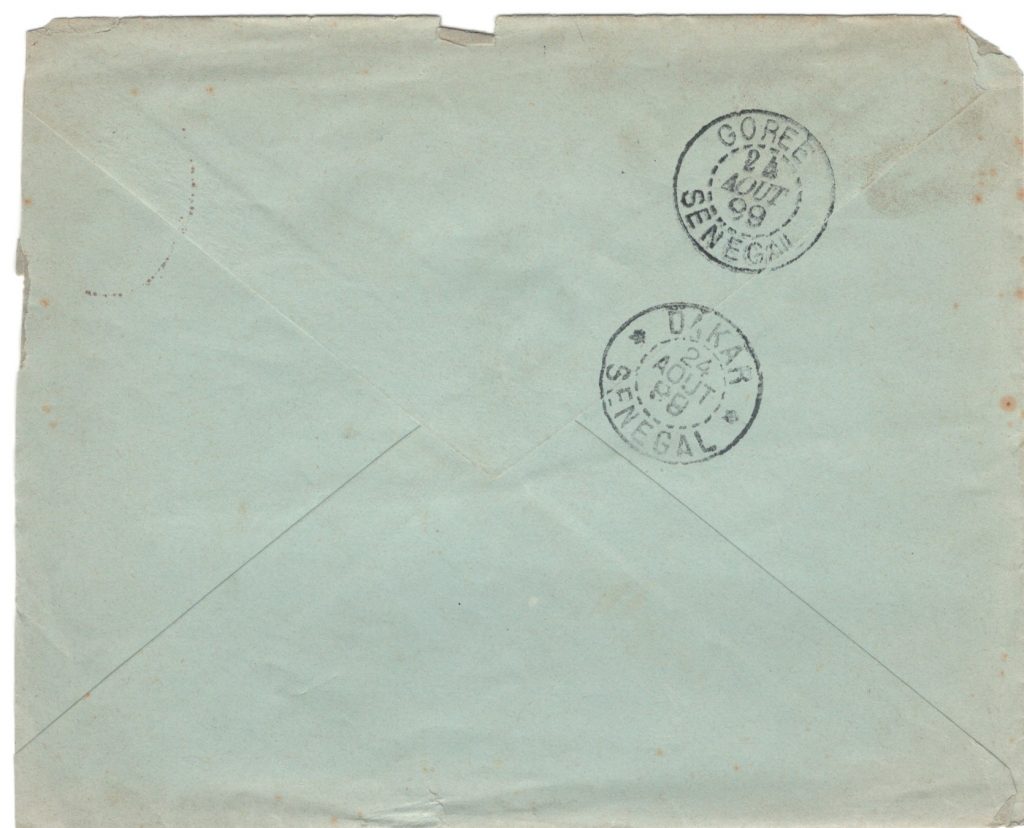

Fig. 18. Cover sent from E. Maurin and Co. in Dakar to Mlle Strickland, Gorée, 8/24/99

Fig. 19. Cover (back) arrived in Gorée, 8/24/99

Ernest Maurin bought tobacco from Peter Strickland, who noted in his diary that Maurin died on 1/14/00. Ernest might have had a daughter who is corresponding here with Mary Strickland. On 2/14/00 Peter wrote a letter in French to Ernest Maurin. The Grand Hotel later took the name, Hôtel de l’Europe.

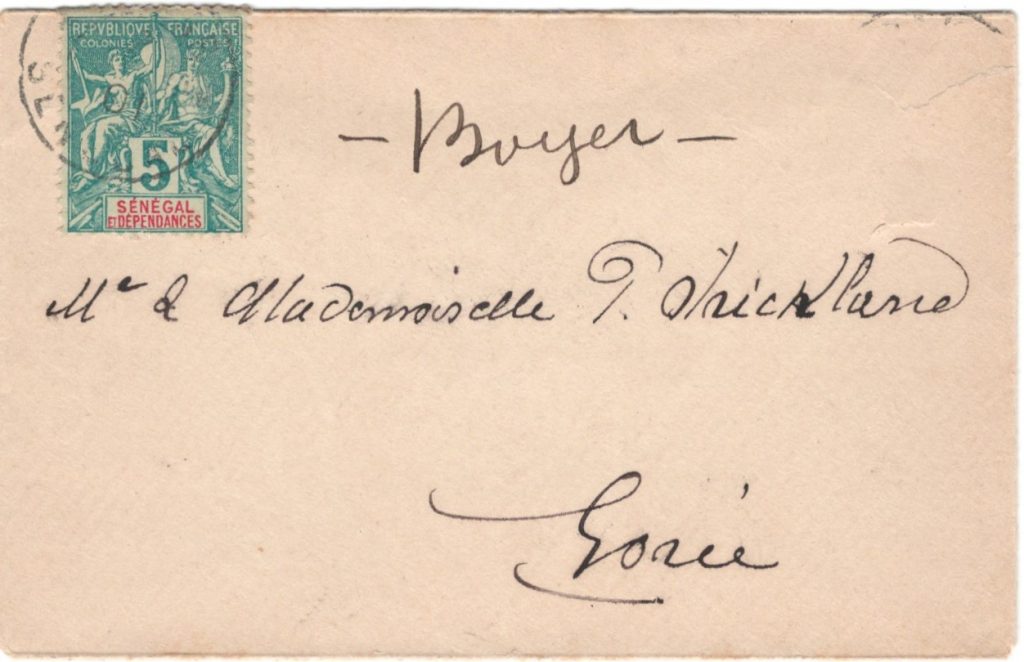

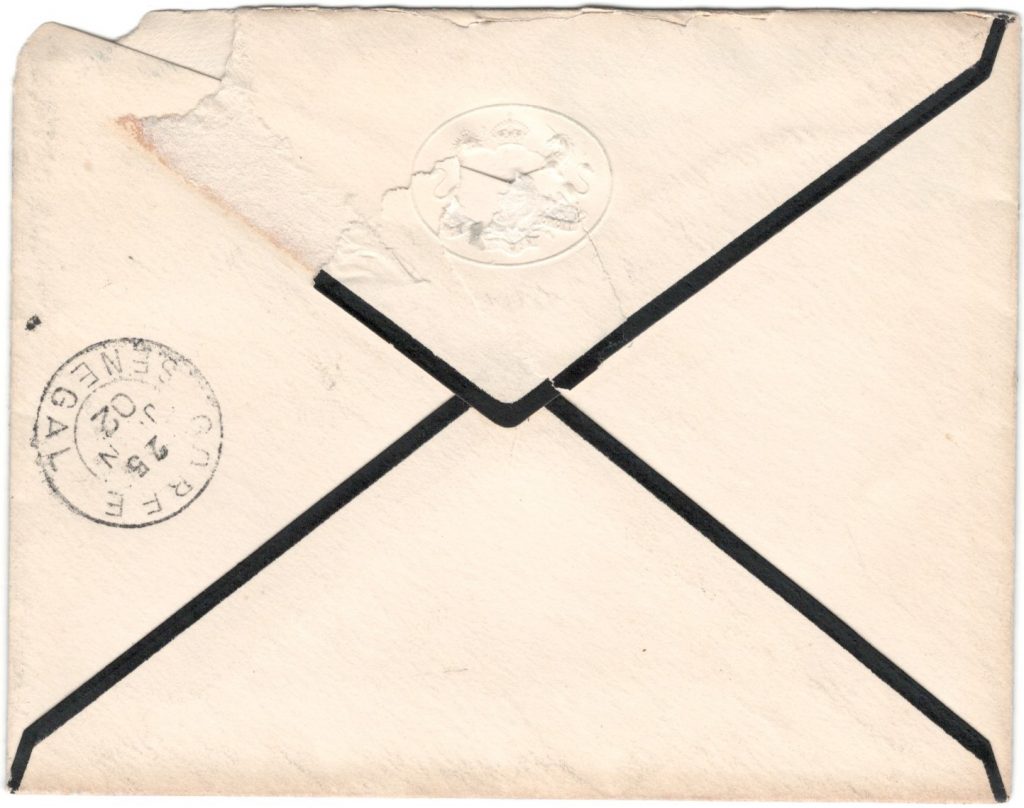

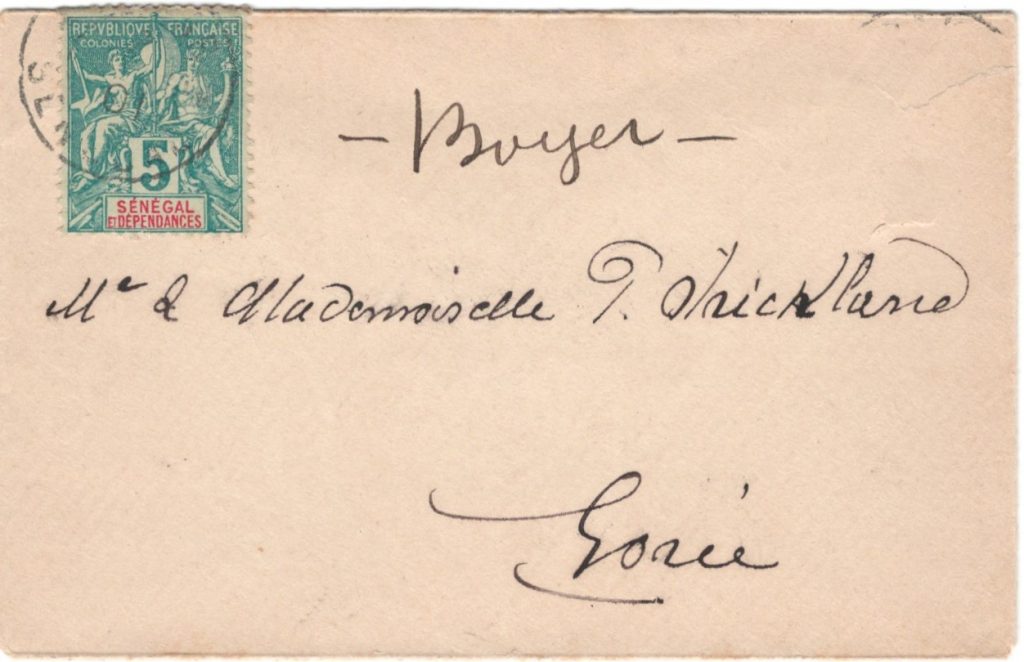

Fig. 20. Cover sent from Boyer, Dakar to M et Mademoiselle P. Strickland, Gorée, ?/ ?/01

The contents of this envelope must have come from Xavier Boyer. Born in 1857 of a French father and Senegalese mother, Xavier Boyer died in 1918 in Marseilles. A businessman living in Dakar, Boyer had family and property on Gorée. He owned one of the two adjacent houses on the northern shore of Gorée overlooking the port that he rented to Strickland from 1880 to 1905. Strickland paid his rent most of the time in cash, but on 4/15/97 paid him in tobacco worth 918 francs.

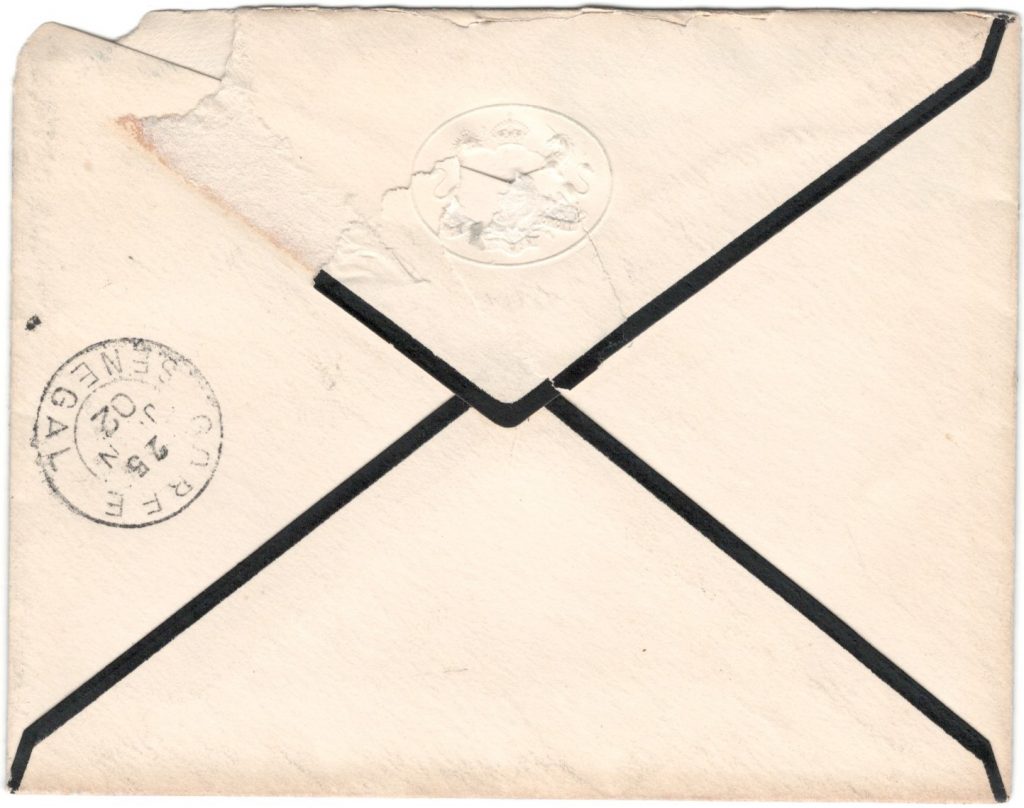

Fig. 21. Mourning cover sent from Dakar to Miss Strickland, Consulat des Etats-Unis Gorée, 6/25/02

Fig. 22. Mourning cover (back) arrived in Gorée, 6/25/02

I am at a loss to figure out what death was mourned by Mary Strickland 14 years after that of her brother George. It was not someone in the family.

Fig. 23. Cover sent from Rufisque to Monsieur Strickland, Gorée, 1/?/02

The contents of this letter came from a man named Vidor. On 2/20/03, Strickland wrote Monsieur Vidor, an employee at the Compagnie Francaise de l’Afrique Occidentale in Rufisque. The subject was a property Strickland owned in Dakar that he wanted to sell for 30,000 francs. Strickland explained, “I bought the place intending to transfer my business there, but the loss of my son changed all my plans.” The deal went through, but not with Vidor.

Fig. 24. Cover sent from Gorée to Mademoiselle et Monsieur Strickland, Gorée, 12/31/02

The message inside Fig. 23 was from Alexander Desproges. Alexandre and his wife Amélie lived on the rue de Dakar in Gorée. Born in Fort-de-France, Martinique, Desproges served as Gorée postmaster. More than a decade after Strickland retired from the consular service, and returned to his home in Dorchester, Mass., he was still corresponding with Desproges to keep abreast of Gorée news.

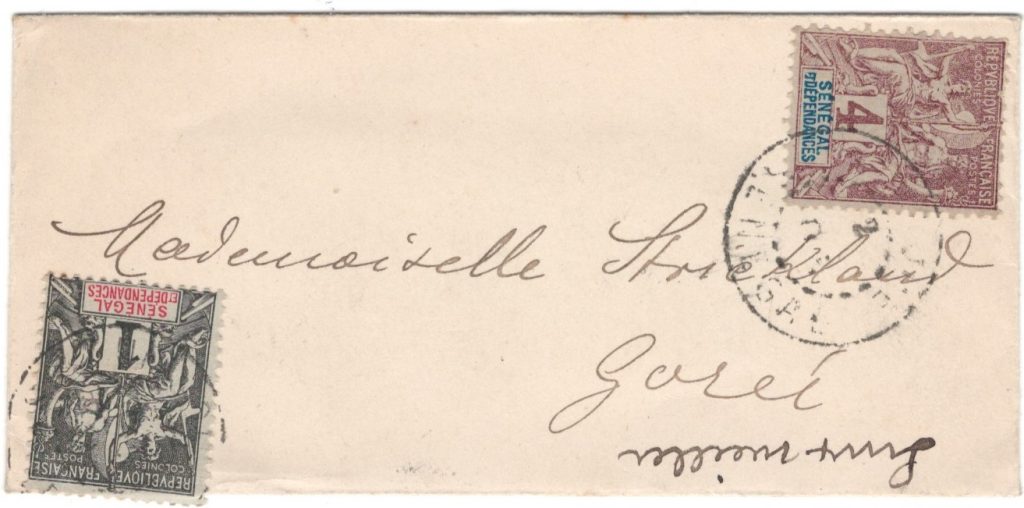

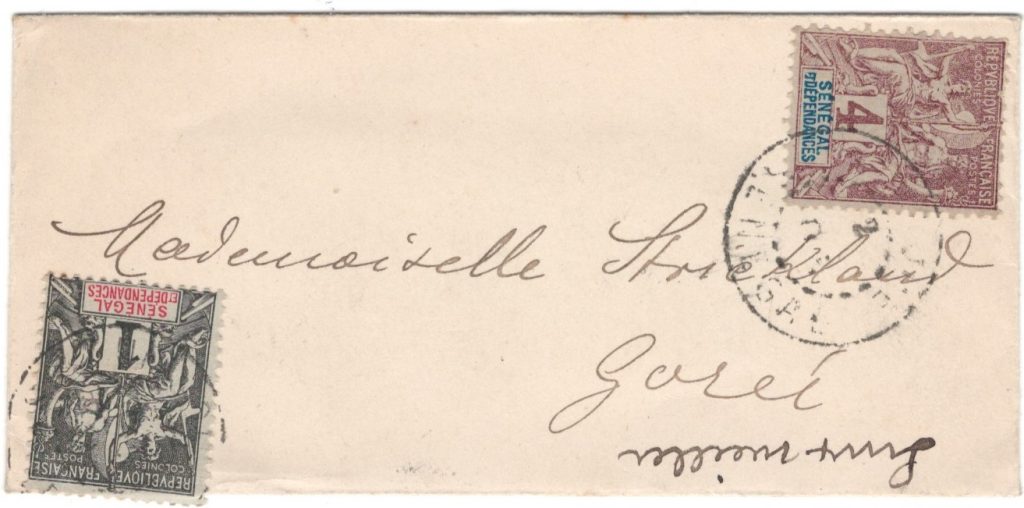

Fig. 25. Cover sent from Rufisque to Mademoiselle Strickland, Gorée, ?/2/05

Not always easy to read dates and names of towns on postmarks of the time. The sender had fun putting stamps on two opposite corners of the envelope, one upside down and the other sideways. Linxweiler is a German name. In August 1903, Strickland was sending cables to a Mr. Linxweiler in Germany about his buying tobacco. It’s been a substantial value added to have 8 names written on the covers, designating the names of correspondents who wrote the elusive contents in this fascinating thread of philatelic covers.

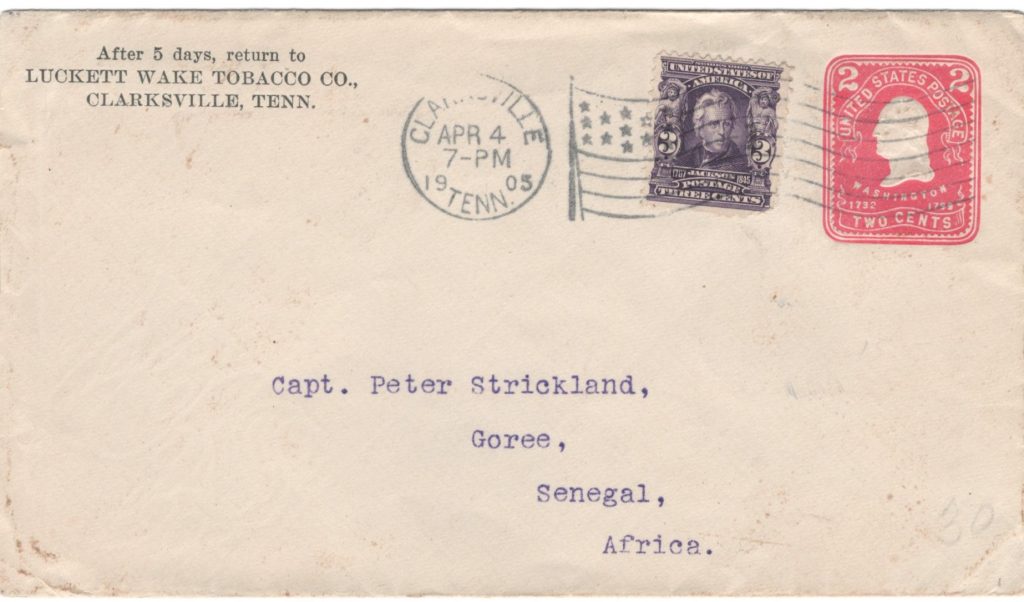

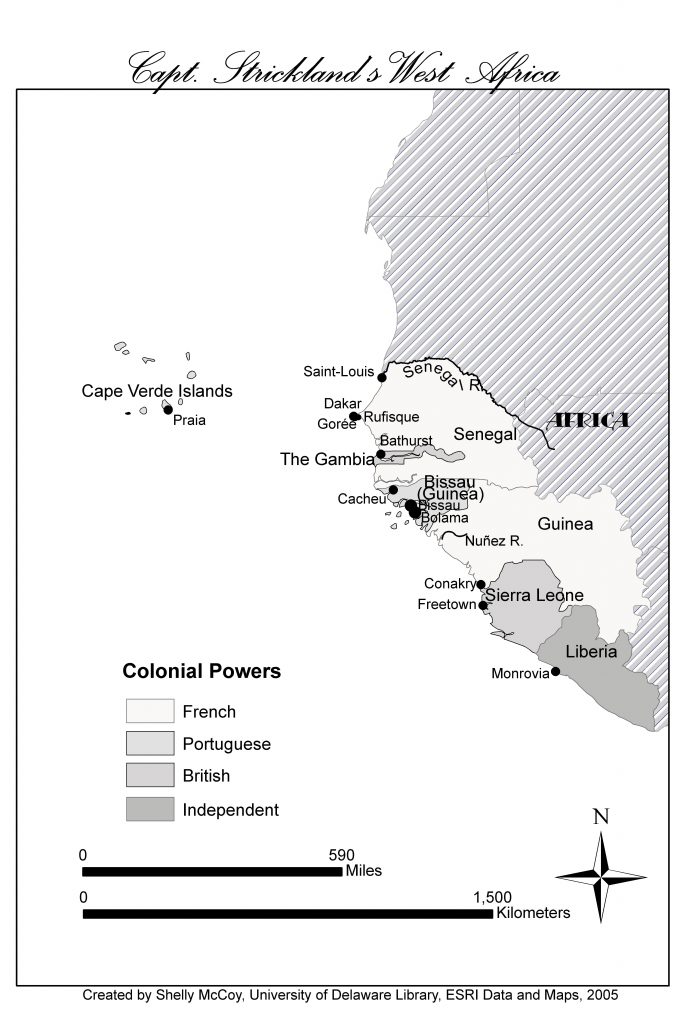

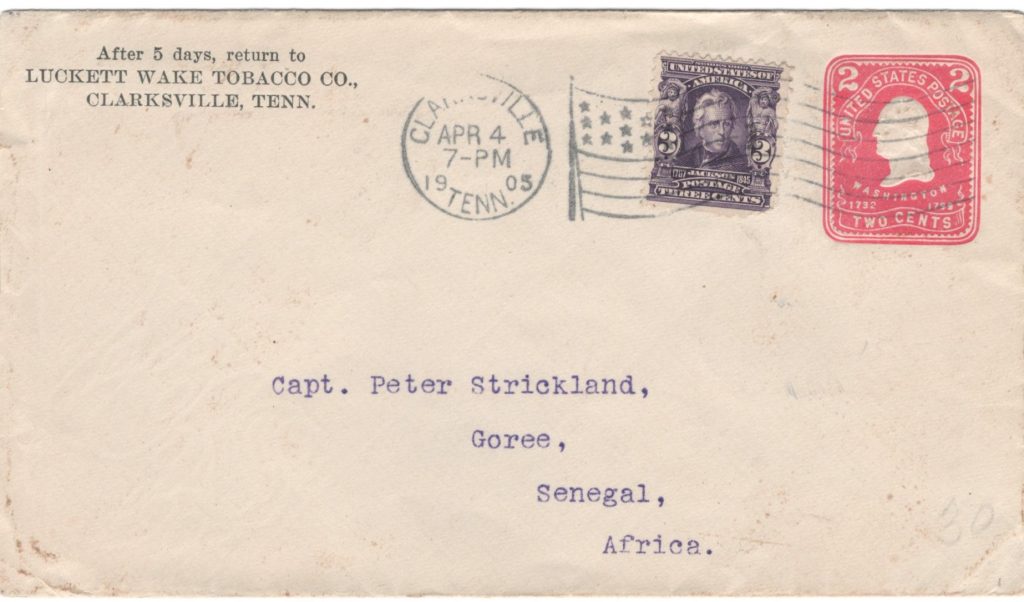

Fig. 26. Cover sent from Luckett Wake Co. in Clarksville, Tennessee to Peter Strickland, Gorée, 4/4/05

Fig. 27. Cover (back) arrived in Gorée, 5/6/05

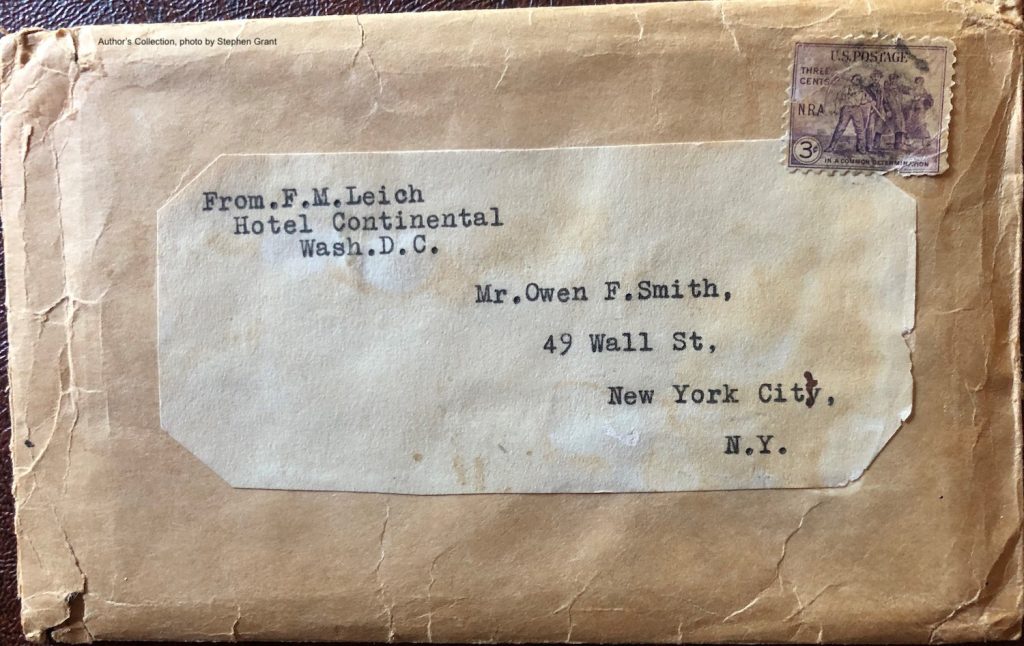

This is the only cover to Strickland that I’ve seen that was typed on a machine. In 1904, the State department sent Consul Strickland a typewriter. He typed one dispatch with it, and concluded that was enough. Luckett Wake Tobacco Co. was founded in 1854 in Louisville, Kentucky. On Mar. 1, 1904, Strickland wrote the Luckett-Wake Tobacco Company to announce that “the French are trying to raise tobacco and cotton in Senegal.” He reported no more on the subject.

After 23 years of consular service in Gorée, Consul Strickland tendered his resignation to the State Department. Having decided to return to Dorchester, Mass. and to Mrs. Strickland, he also had to find someone to take over his duties as commission merchant for the American tobacco company, Luckett-Wake of Clarksville, Tenn. He chose Maurel Frères of Senegal. Strickland wrote Luckett-Wake on 12/20/04 to introduce the firm. “Maurel Frères may be as good a party as we are likely to find to carry on the business . . . Maurel Frères is a rich, thoroughly reliable, and competent firm, located on the spot. . . Maurel Frères is and has been the most popular of the larger firms. . . Maurel Frères have large factories at Dakar, Rufisque, at all the points along the line of the railroad into the interior, in the Rivers Casamance & Gambia.”

One of Strickland’s last visitors on Gorée was the census taker, who counted him among the island’s population of 1,560 inhabitants. Of this total, 1,312 were indigenous, 156 were mixed race, and 92 were of European stock.

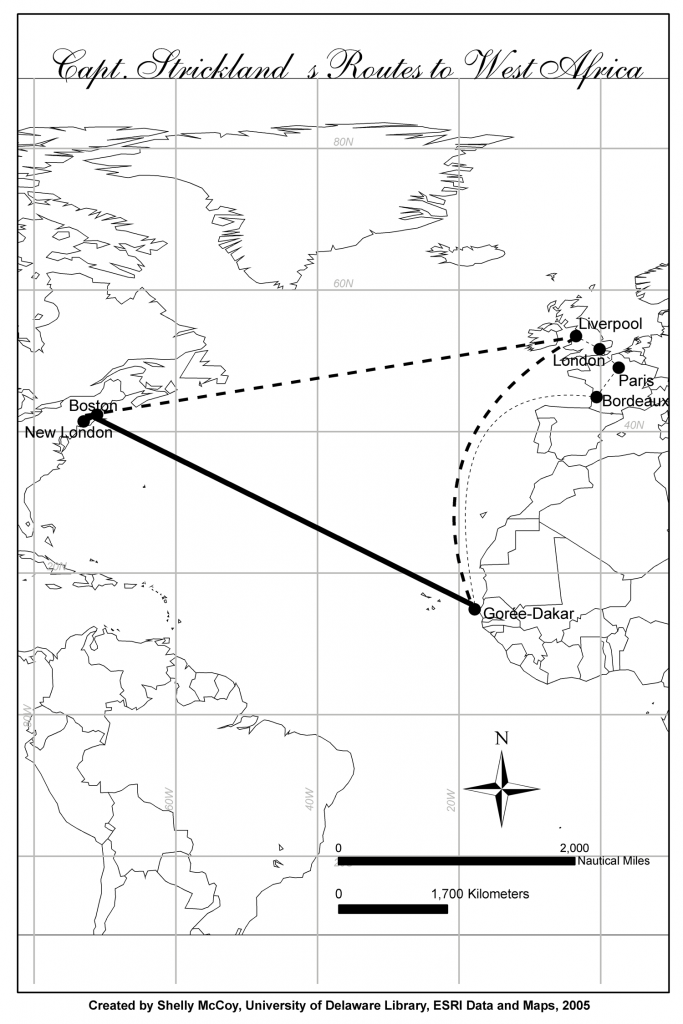

On July 21, 1905, Capt. Strickland and his daughter Mary stepped on the French steamer La Cordillère in Dakar, bound for Bordeaux. They took the train for Paris and crossed the Channel on Sept. 22. In Liverpool they boarded the White Star Line’s RMS Republic for Boston. The captain could not help comparing how he first arrived in Senegal and how he departed. He had arrived 40 years earlier on the schooner Indian Queen, a 78-feet-long, 118-ton vessel. In contrast, the RMS Republic weighed 15,385 tons and was 570 feet long.

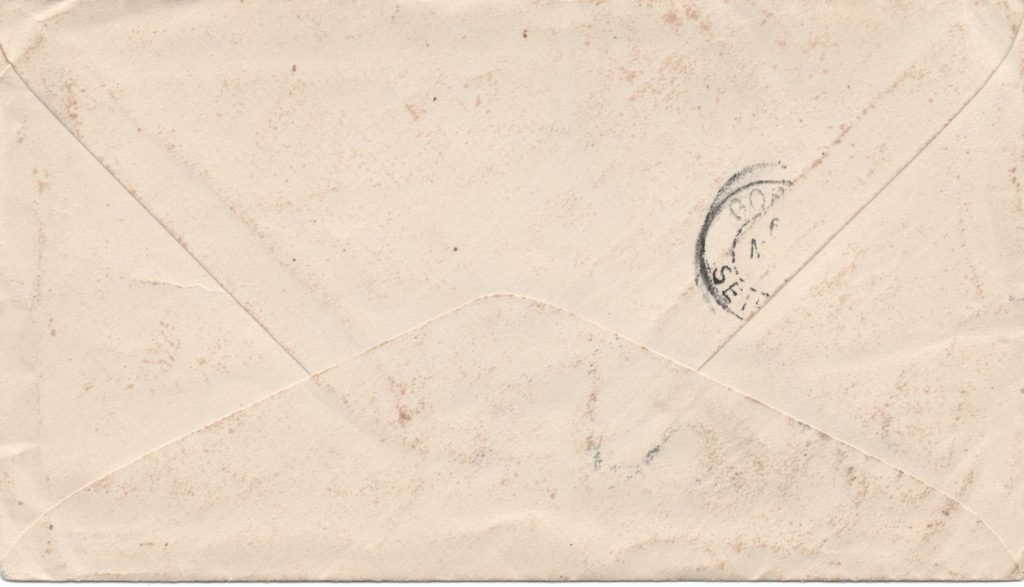

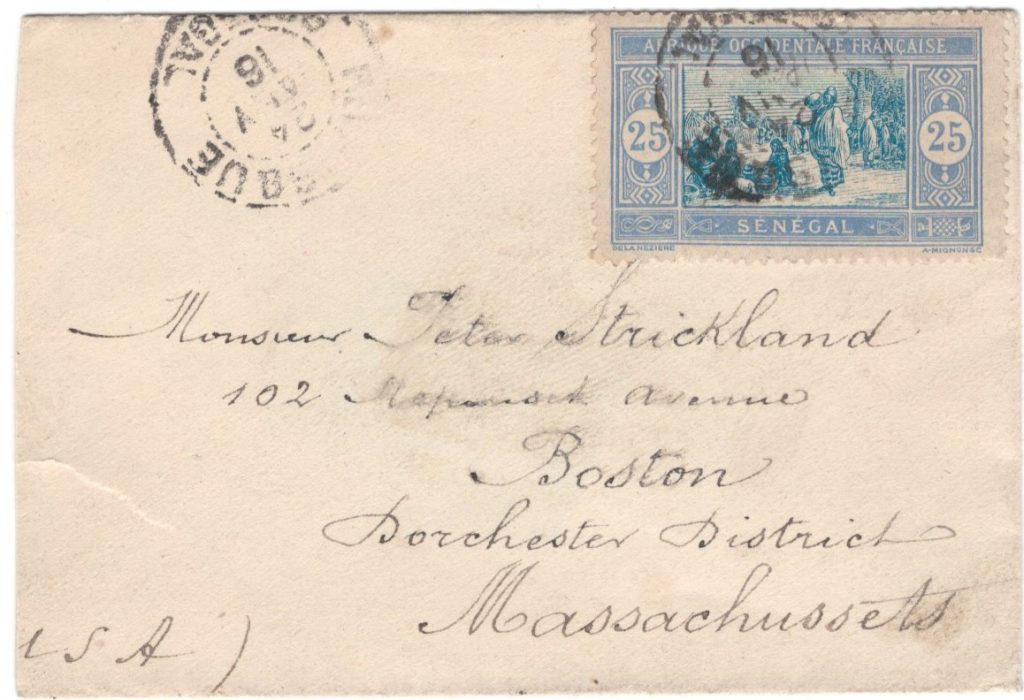

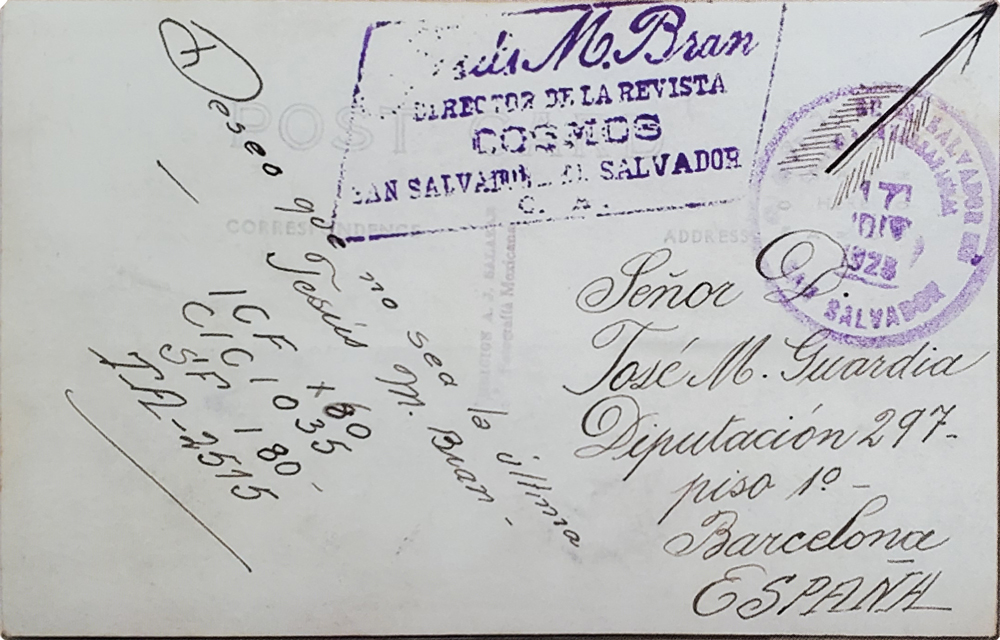

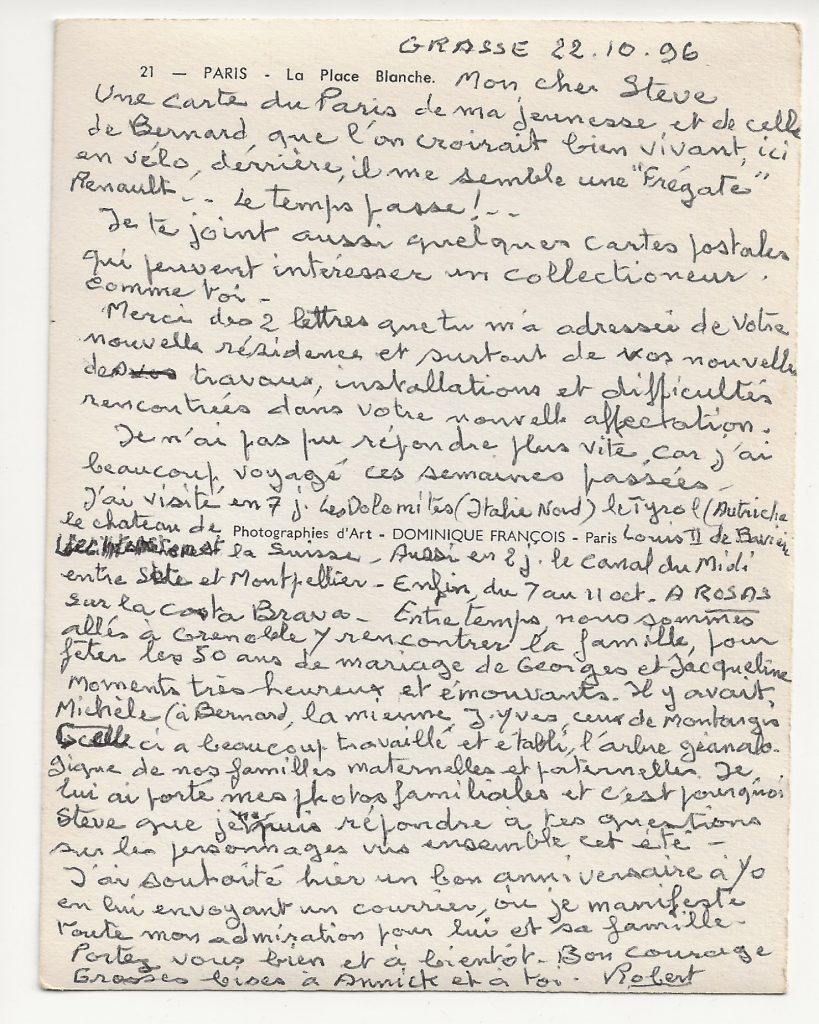

Fig. 28. Cover sent 1/24/16 from Rufisque to Peter Strickland in Dorchester, Mass.

This is the only cover I’ve come across sent to Peter Strickland in the US. It is notable that this first-ever presentation of mail to Peter and Mary Strickland in Senegal and in the US spanning 3 decades starts and ends with mail from Rufisque. We’ve known quite a lot about Peter Strickland’s life through the documents he left behind; we know little about his wife and daughters. The mail to Mary in this post constitutes an unexpected value added, opening a window on her communications.

From 1905 until 1912, Strickland maintained a role in facilitating tobacco sales in Senegal through Luckett-Wake, cutting his sales commission from 5% to 1½%. On Jan. 10, 1913 he reflected on his last 6 decades.

It seems to me decidedly queer not to be connected in any manner with business. Since I was in my “teens,” I have had work almost continually so that it has seemed to be a part of my nature to be connected with it, and I have now got no particular work or business to think of. But I am 75 years of age, and have perhaps done my share of the “World’s Work,” although I have a feeling and am glad that I have got it that I should be willing to do more if I am given strength and opportunity as perhaps I shall be. . . One hardly likes to feel that he has no longer anything to do in the world except to exist and to give all his attention to those wants of his nature connected with existence. One still longs to do something which shall count for the world, and I think most of those who have generous natures manage to make themselves useful in some manner clear through to the end.

Fig. 29. Consulate and Strickland residence on Gorée Island, Senegal, 1880–1905. Strickland sent this postcard with his drawings and commentary to the State Department in Washington, D.C.

Fig. 30. Strickland residence at 102 Neponset Ave., Dorchester, Mass., 1871–1945

References, quotations from:

Peter Strickland Manuscript Collection 69, Mystic Seaport Library, Mystic, Conn.

MSS 171 Peter Strickland Papers, 1857-1912, University of Delaware Morris Library Special Collections, Newark, Del.

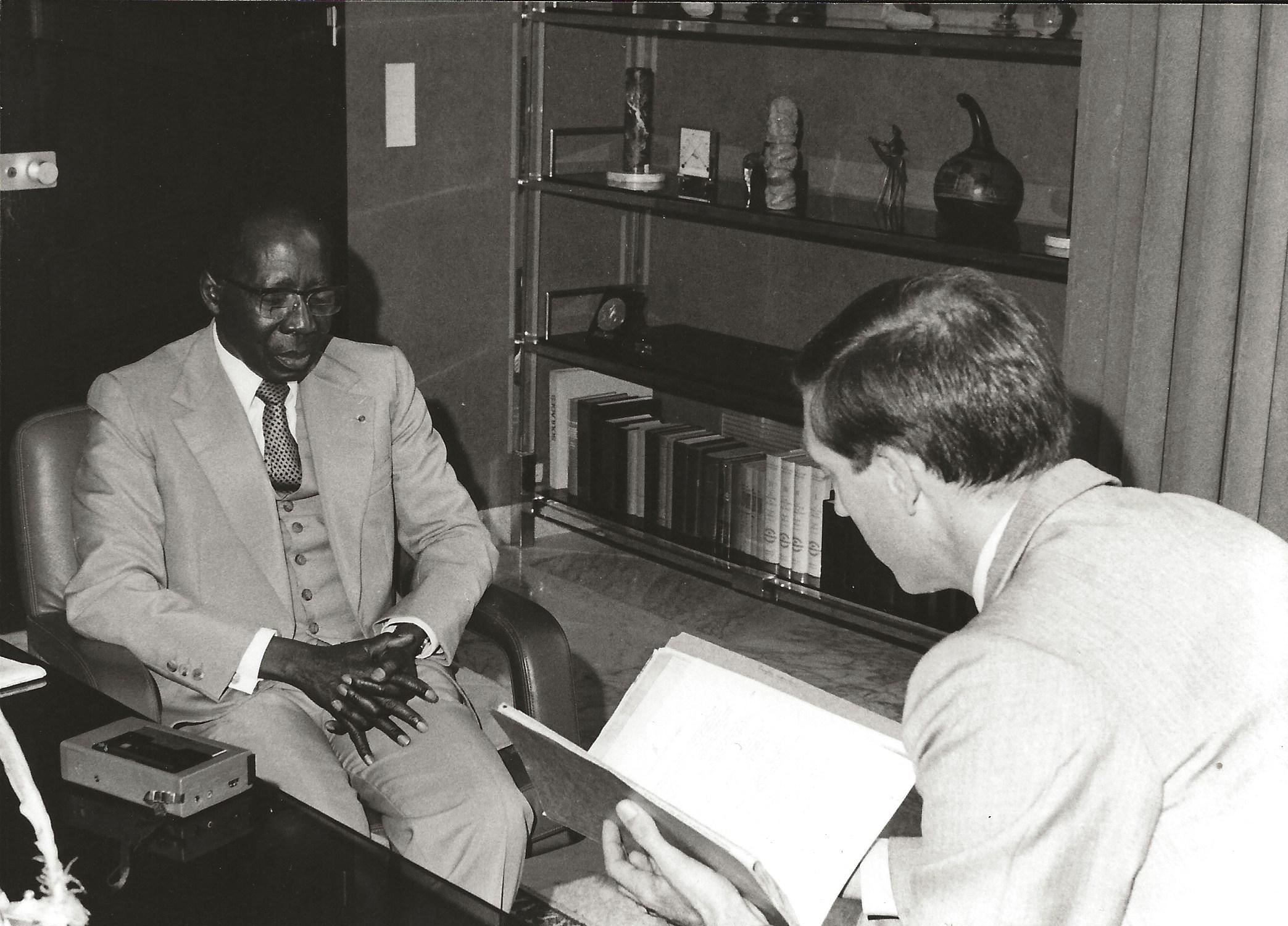

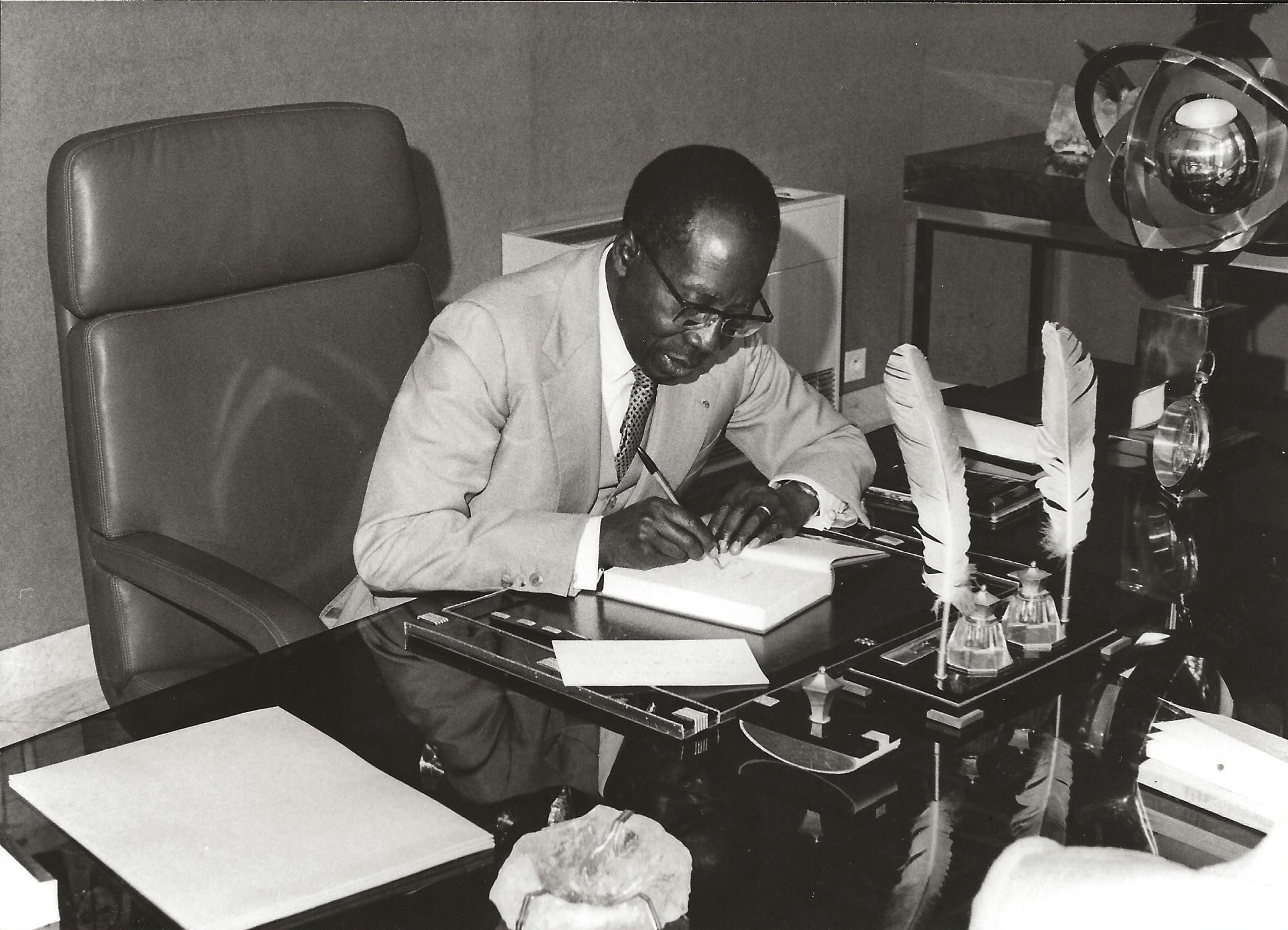

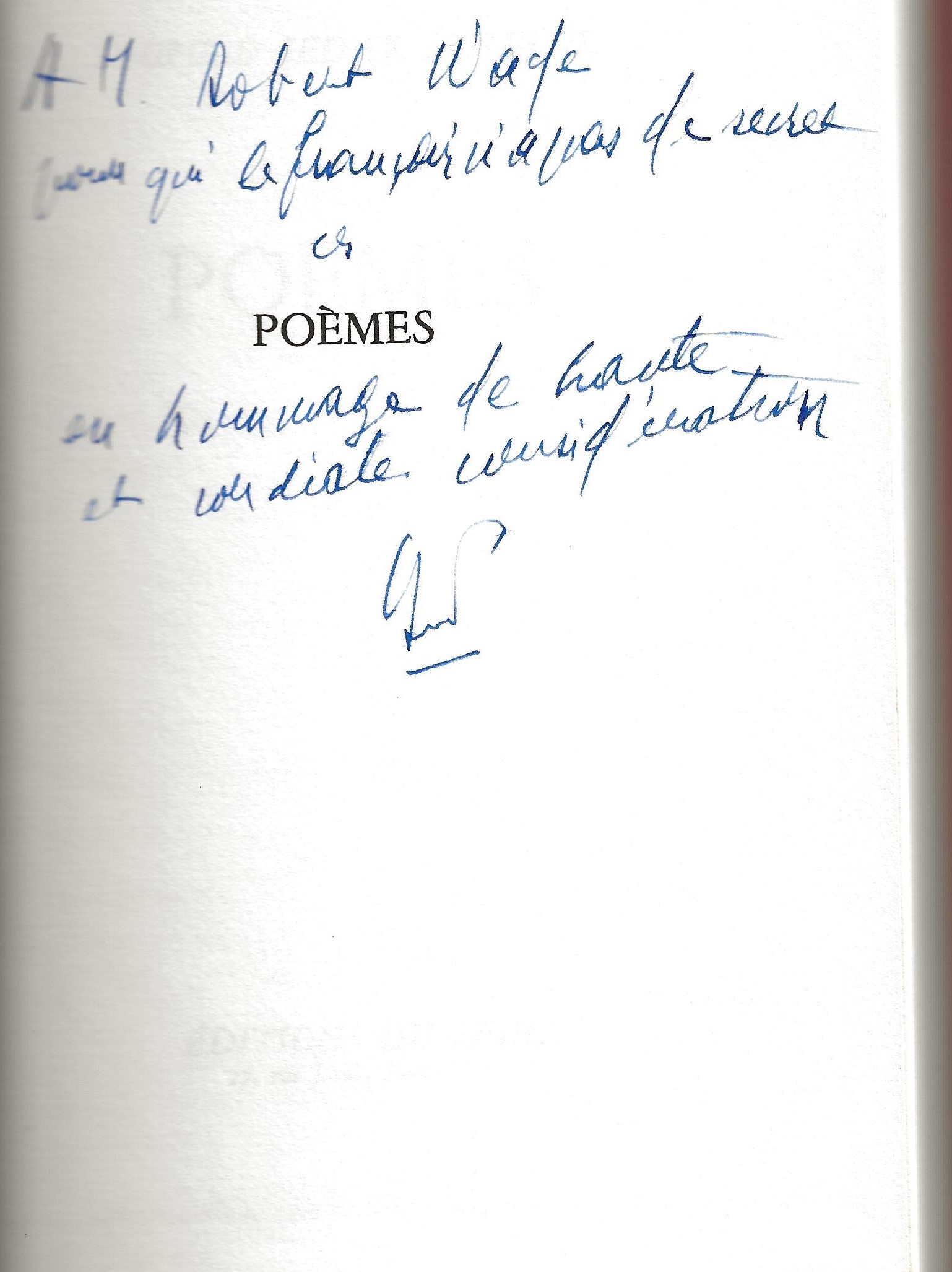

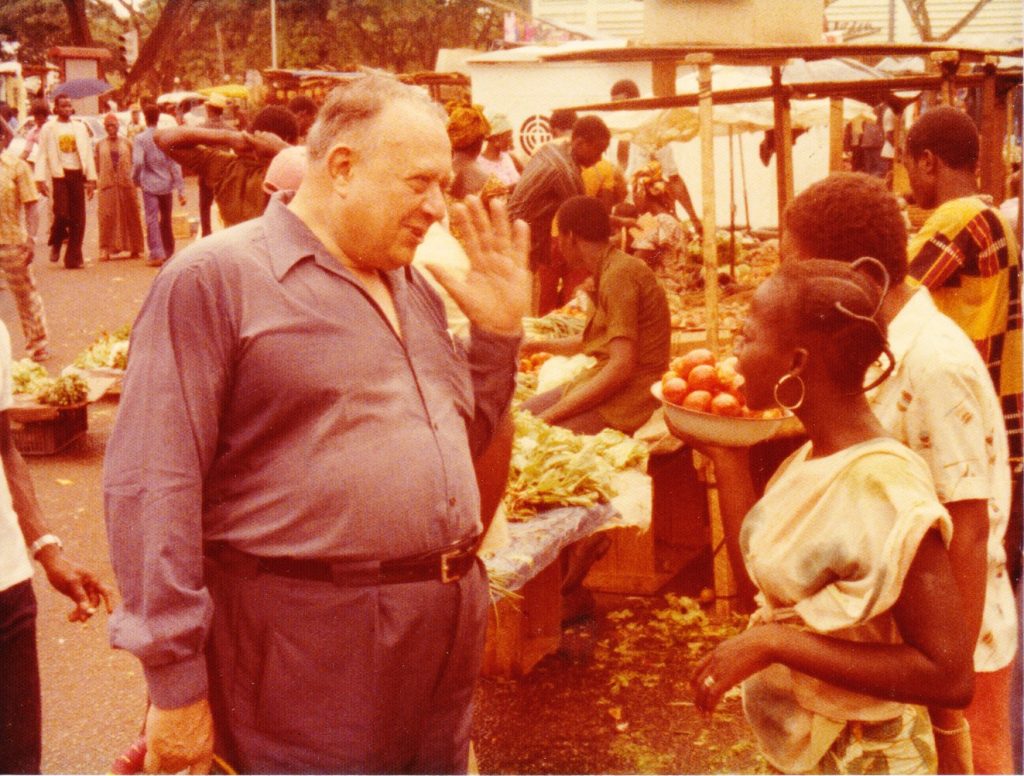

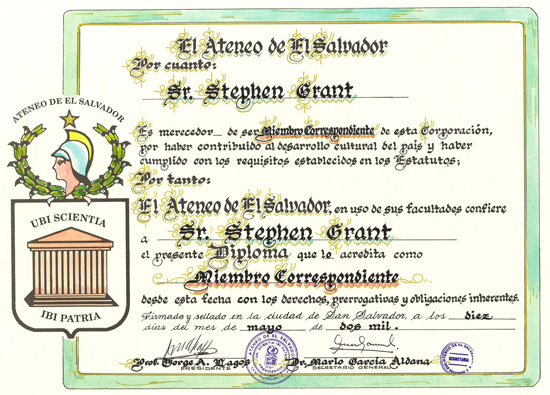

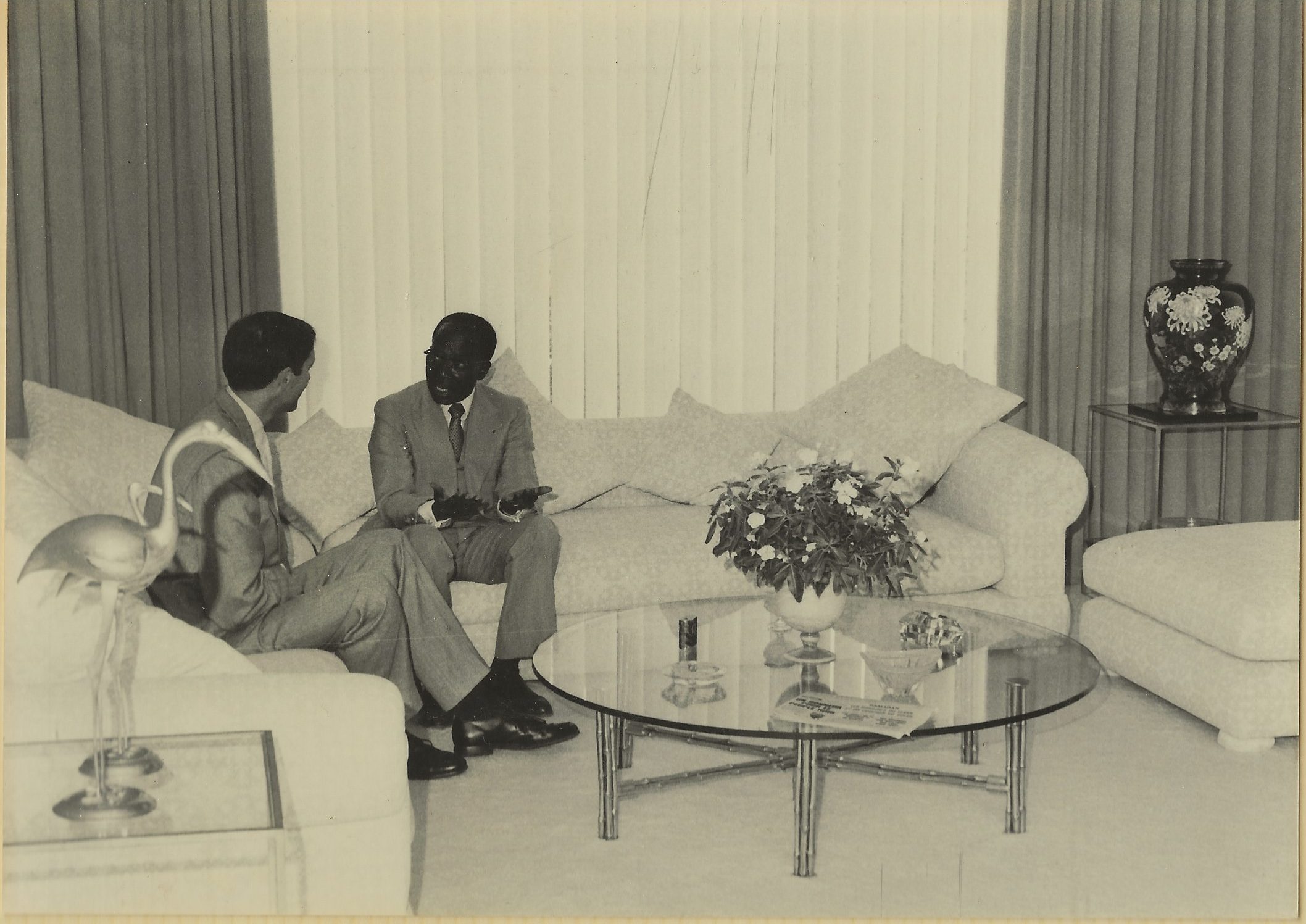

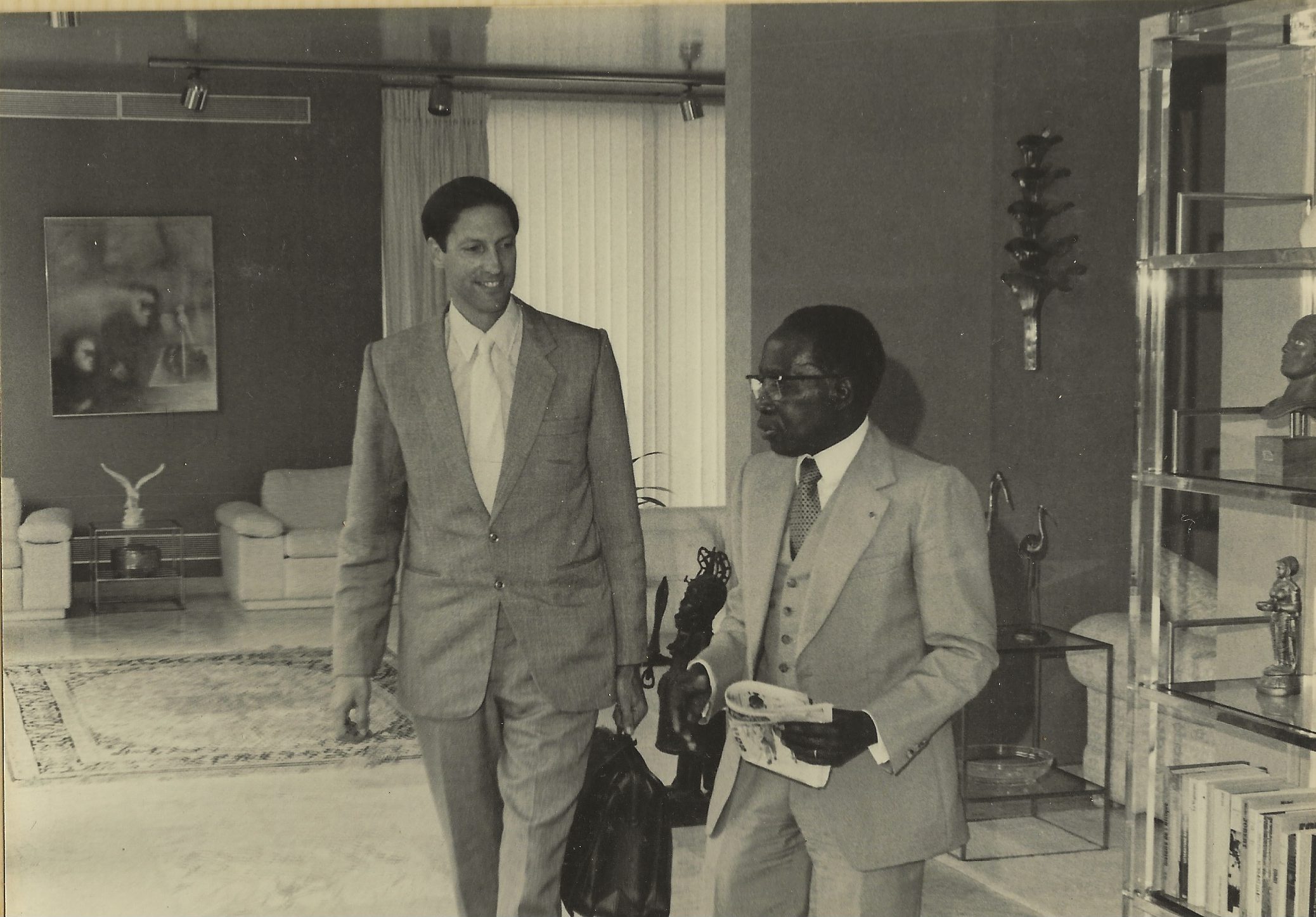

In 1972, President Senghor traveled to

In 1972, President Senghor traveled to My 1983

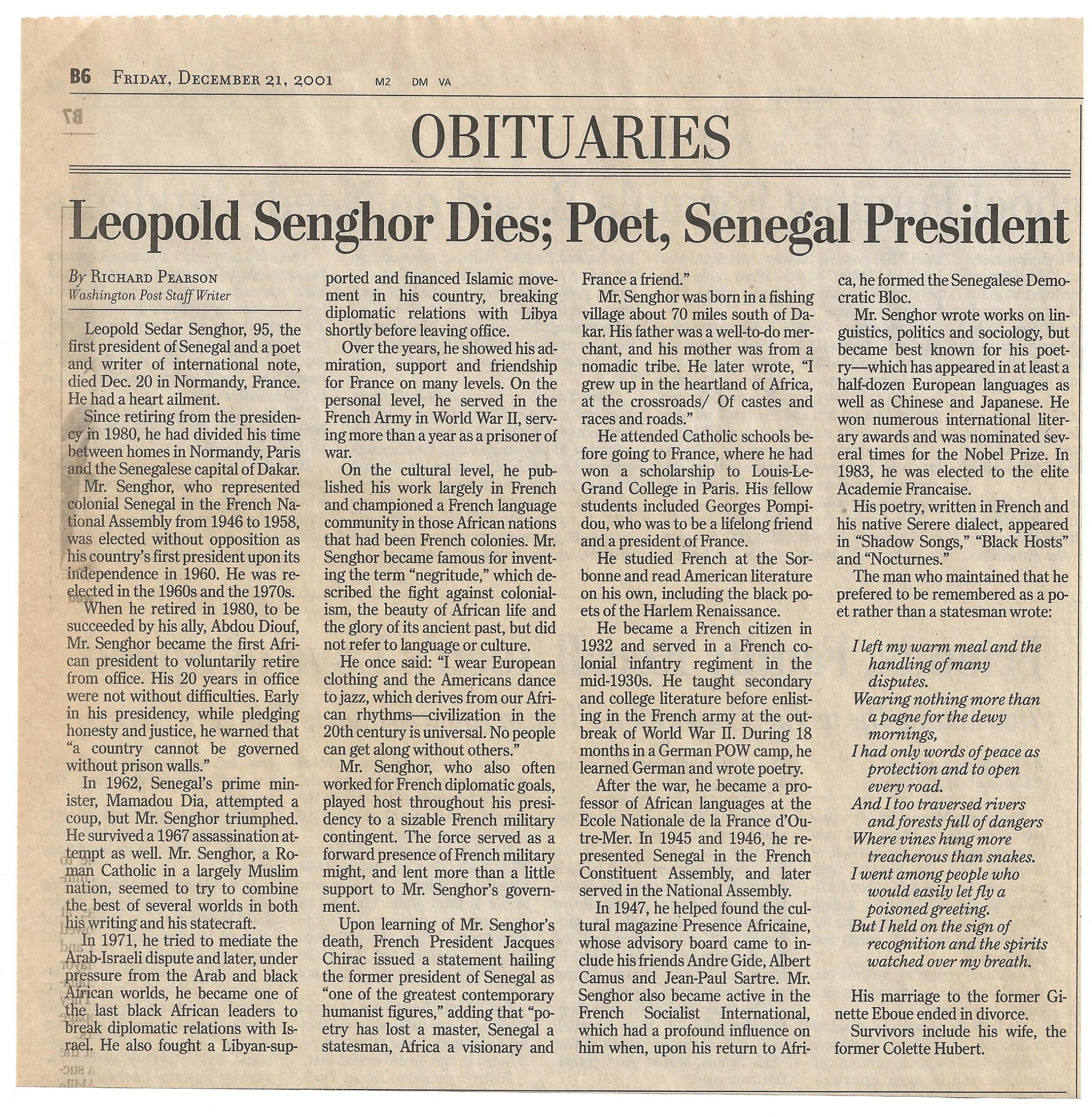

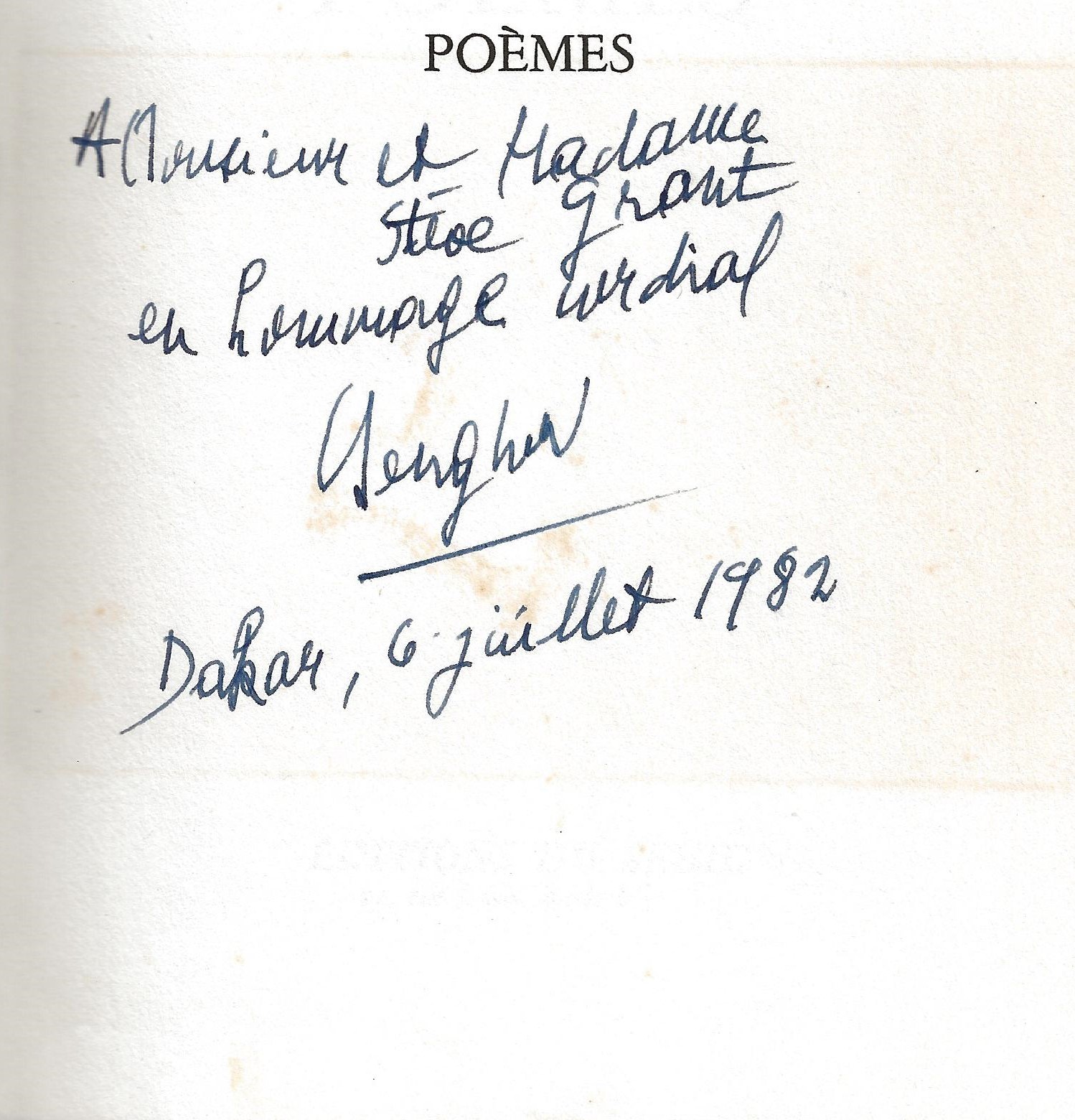

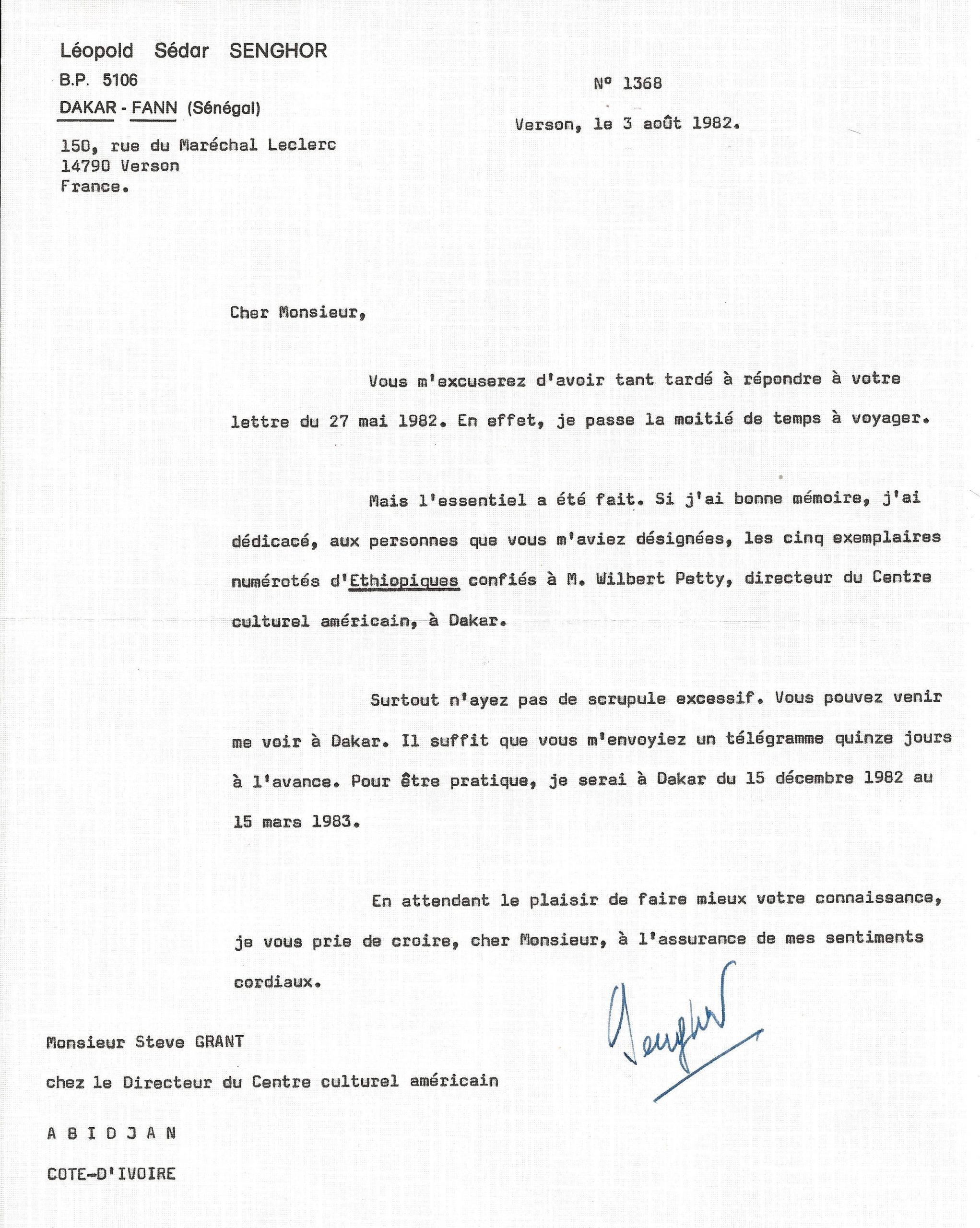

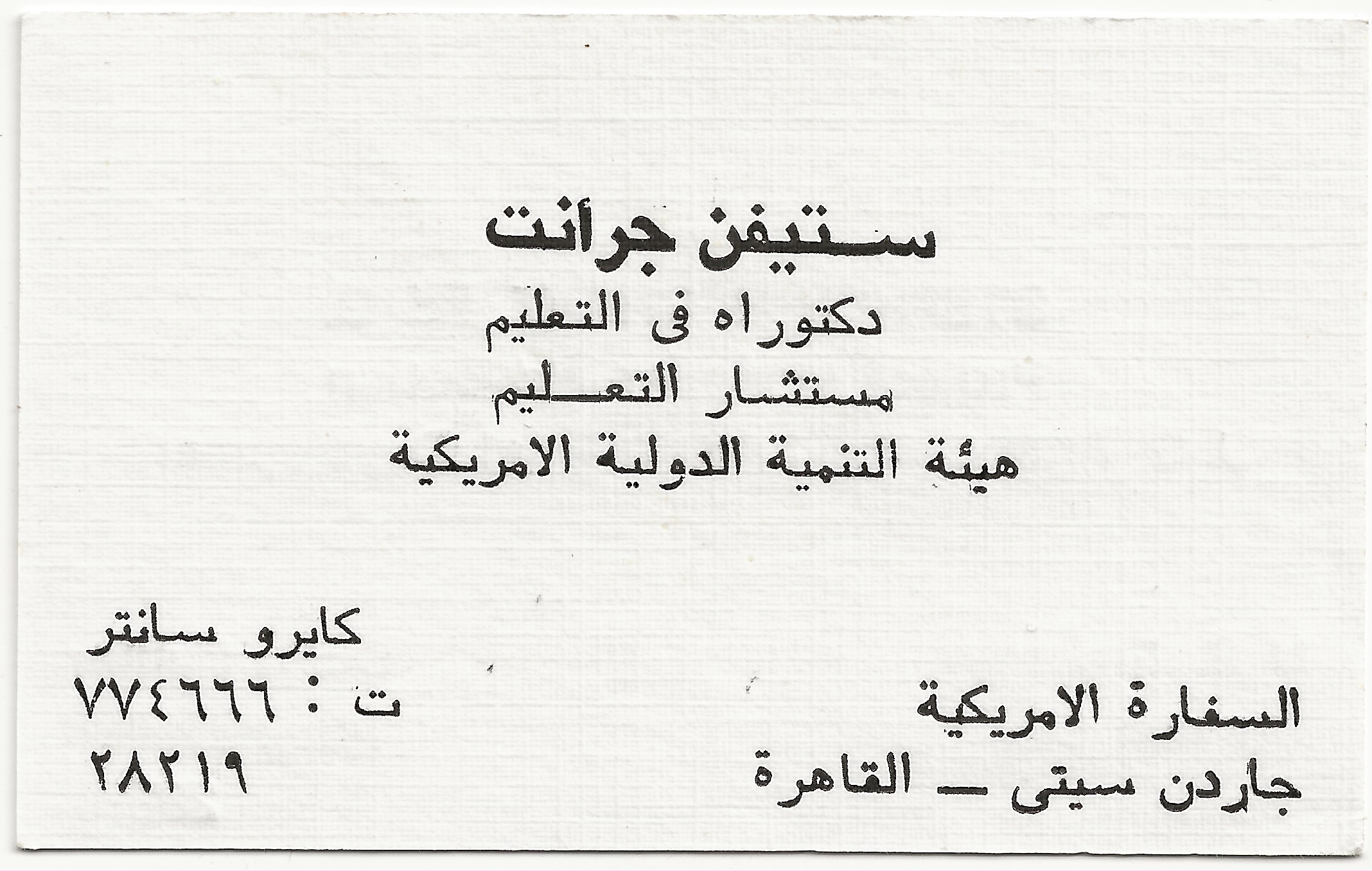

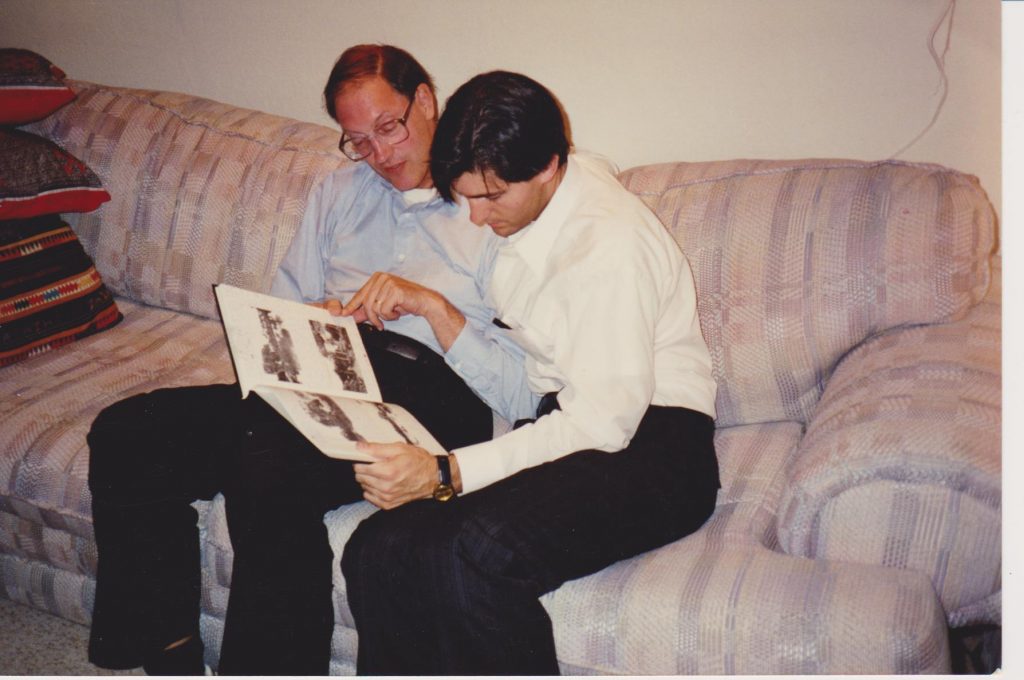

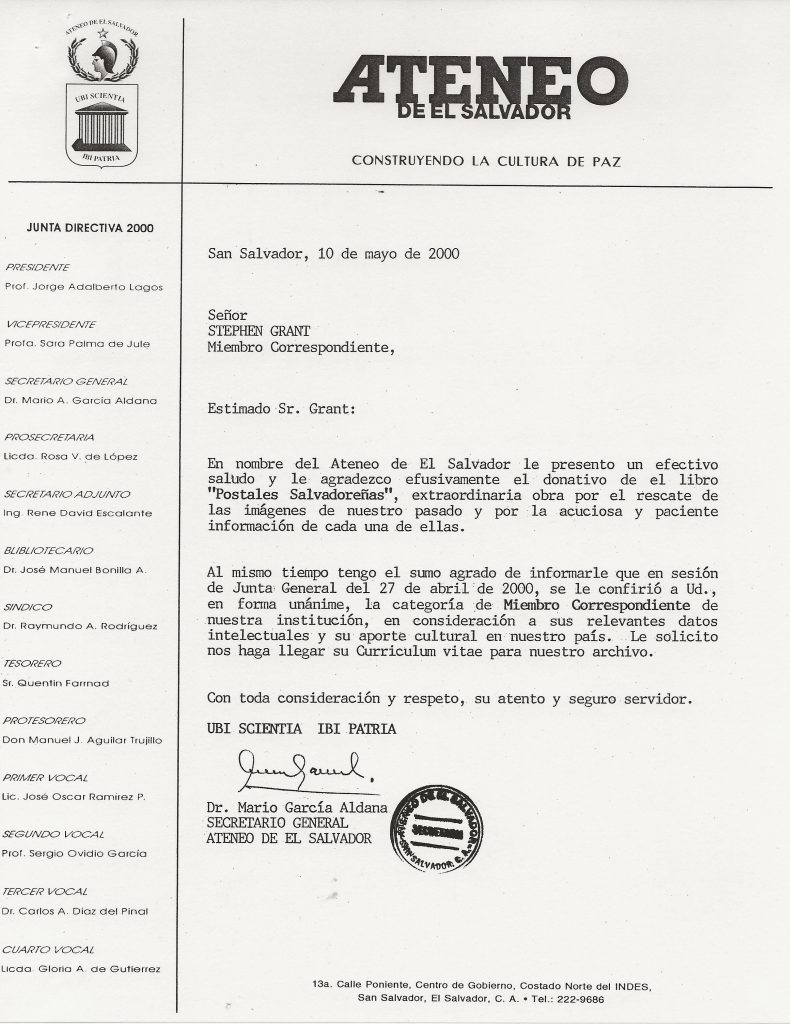

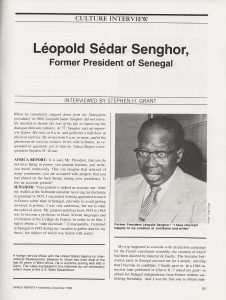

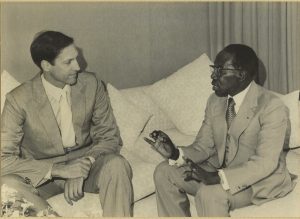

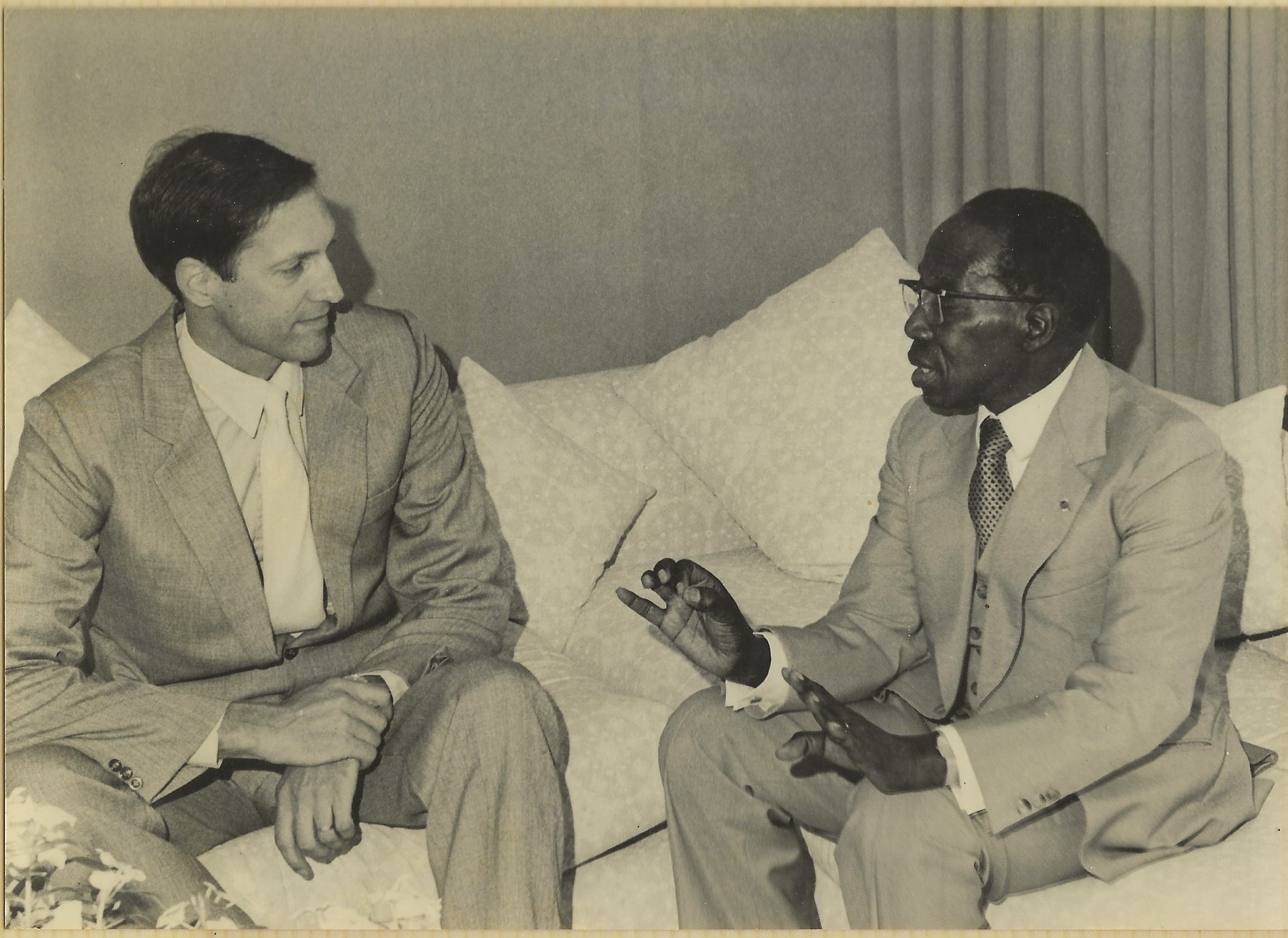

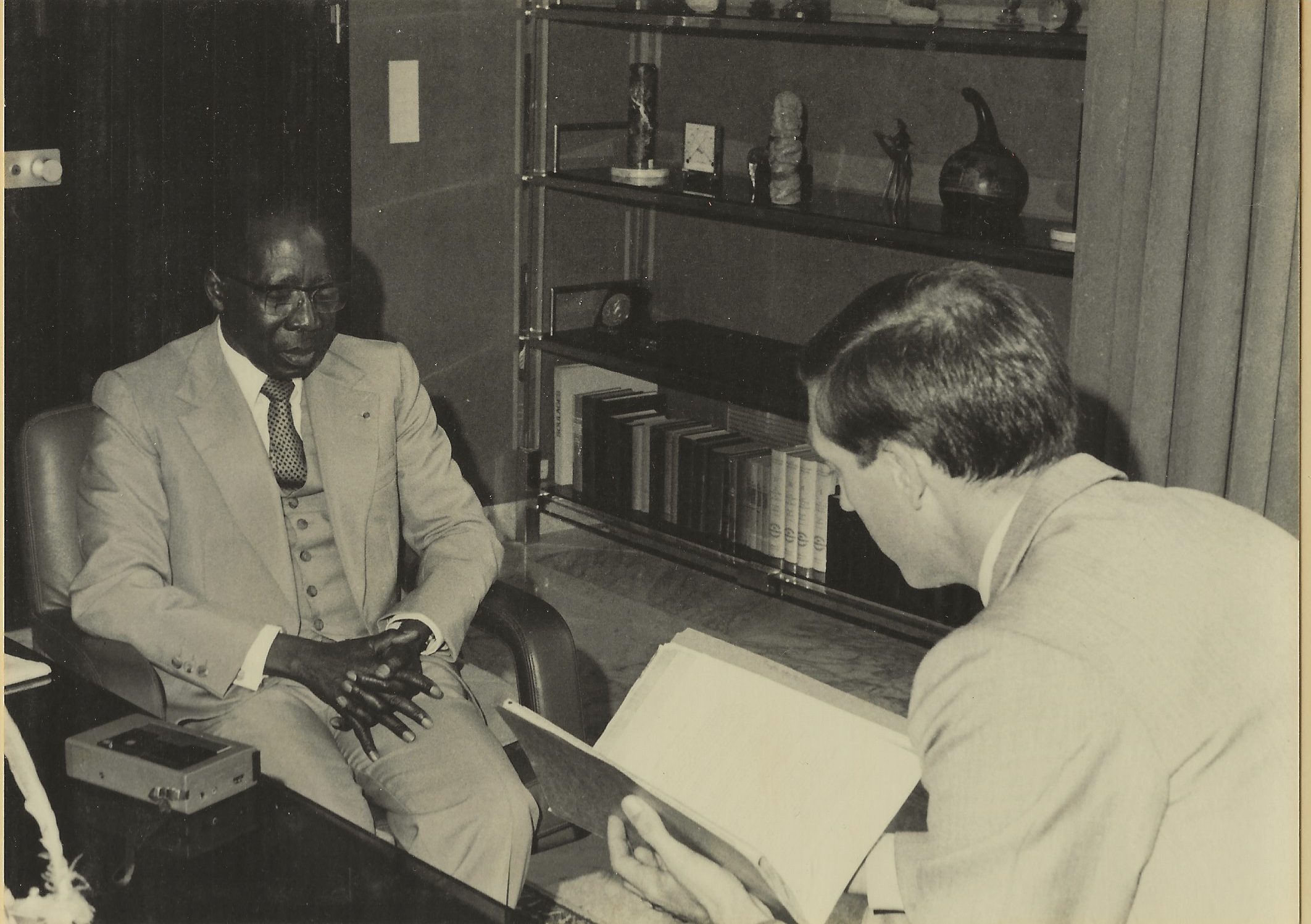

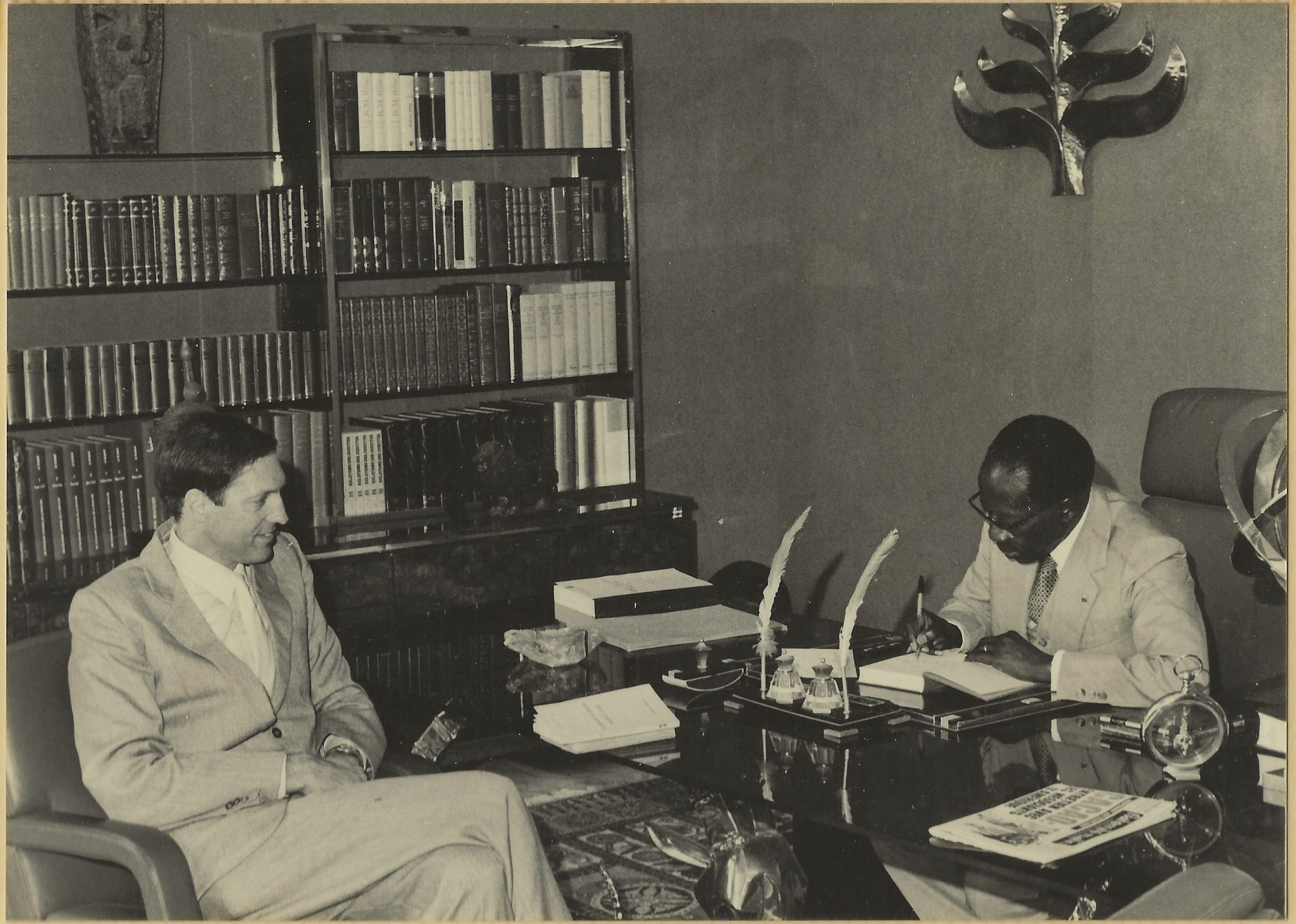

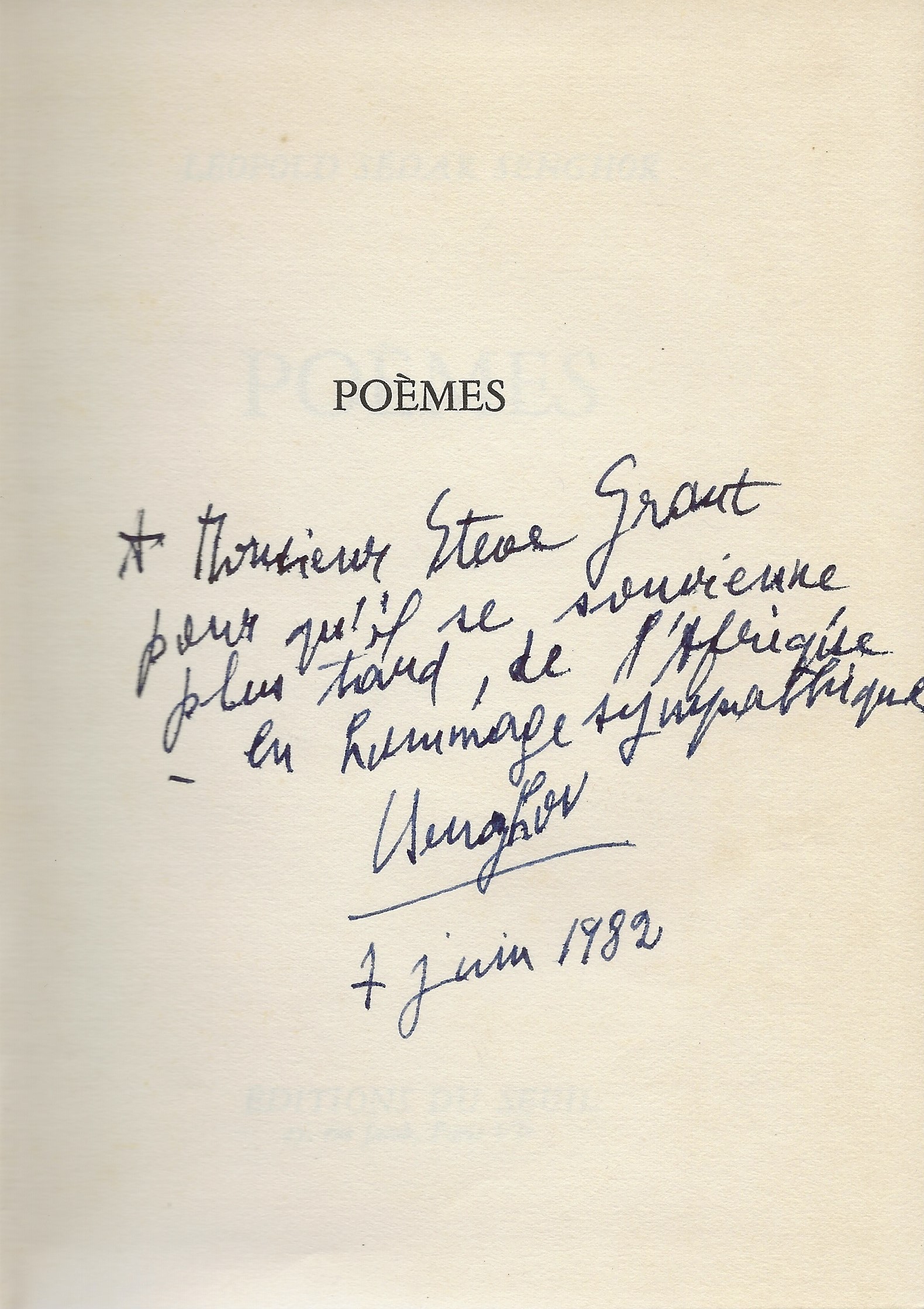

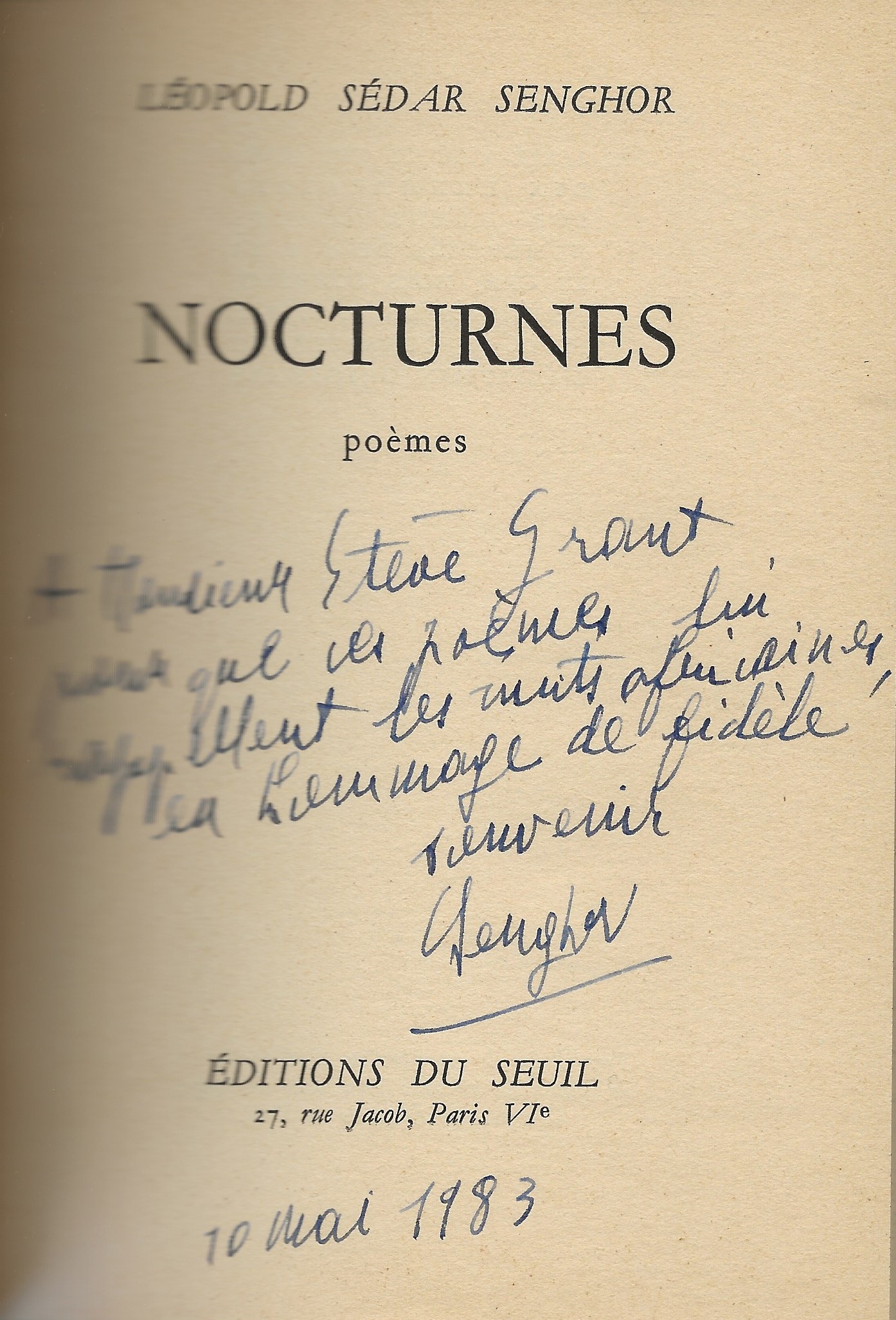

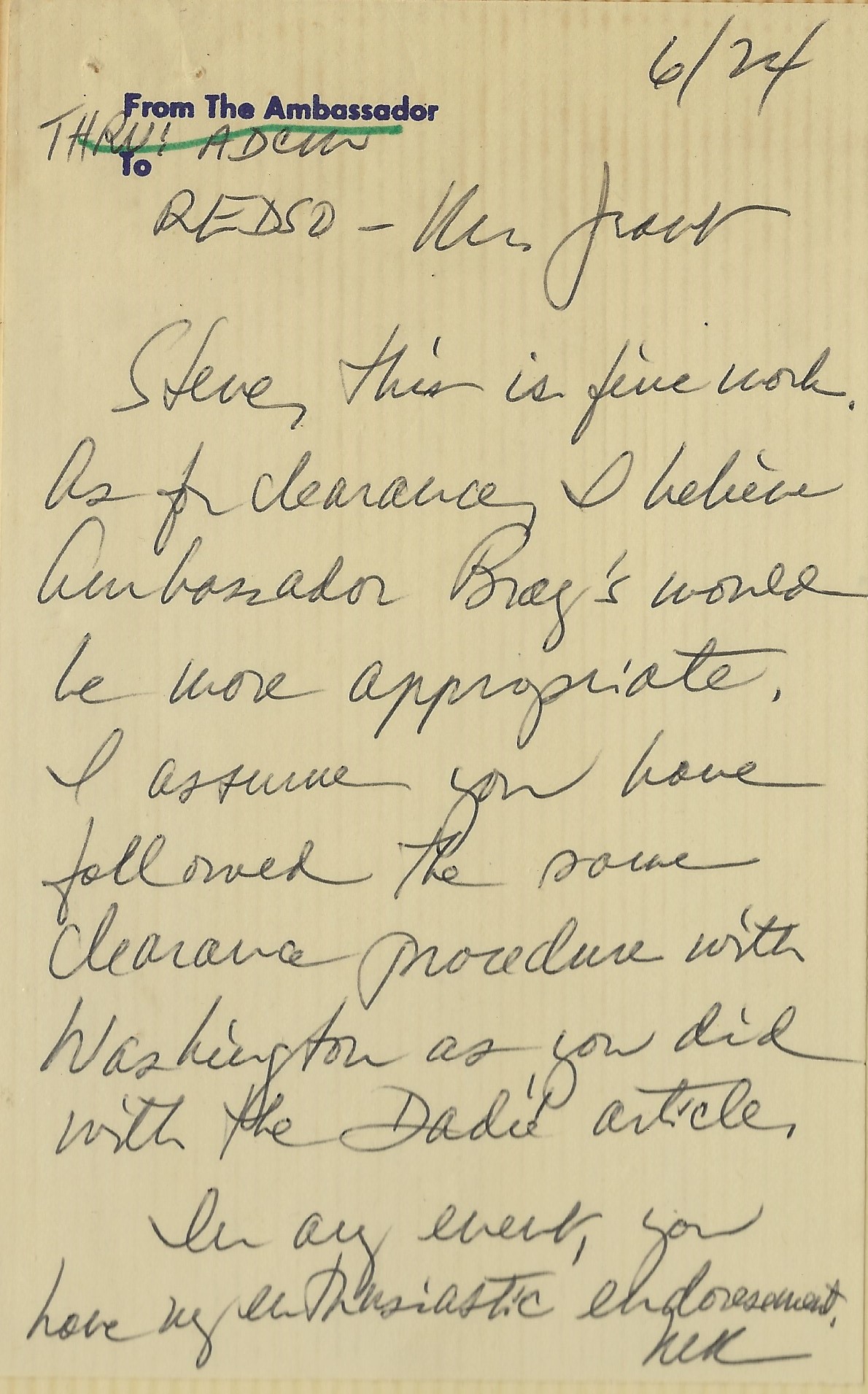

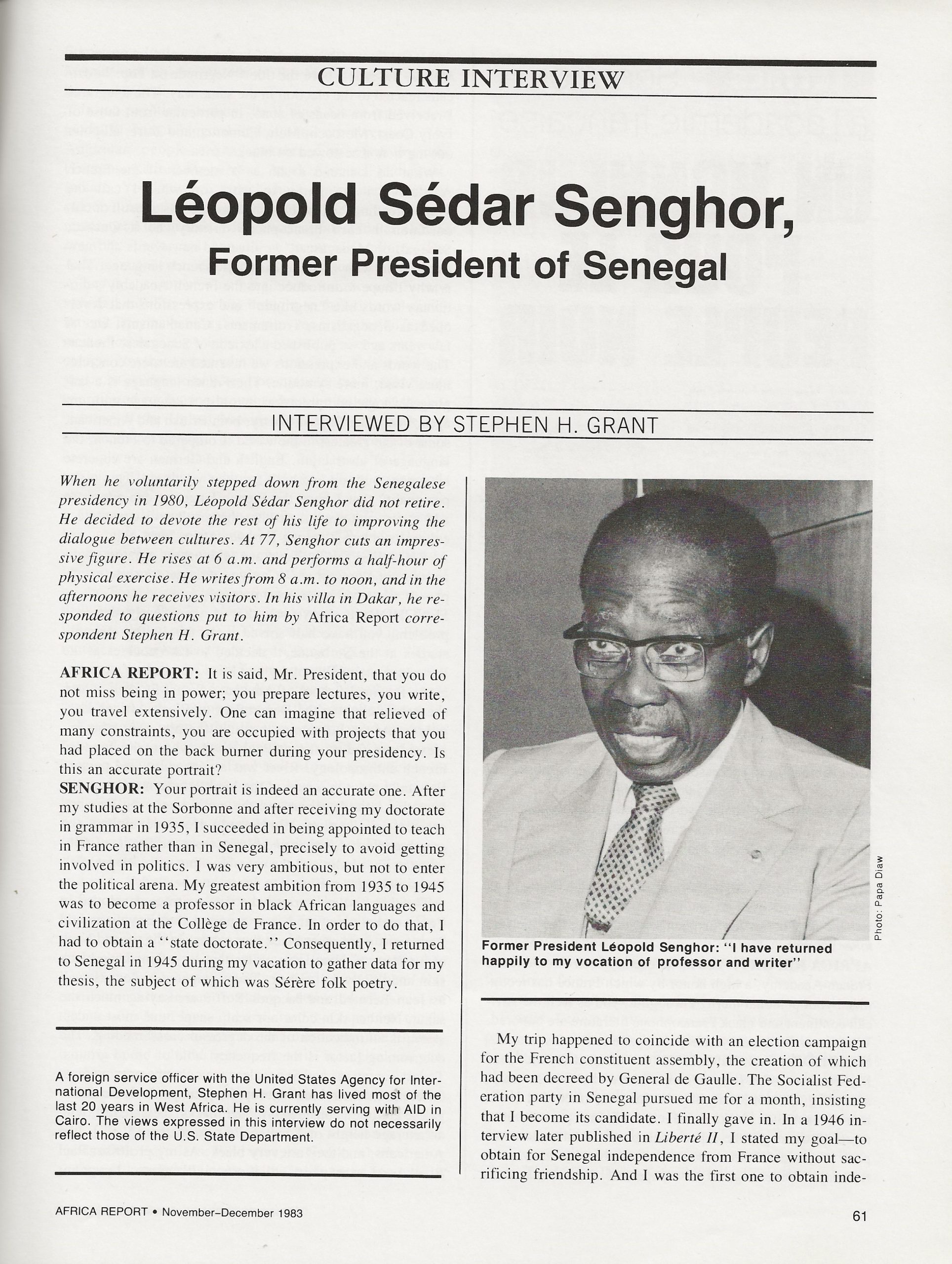

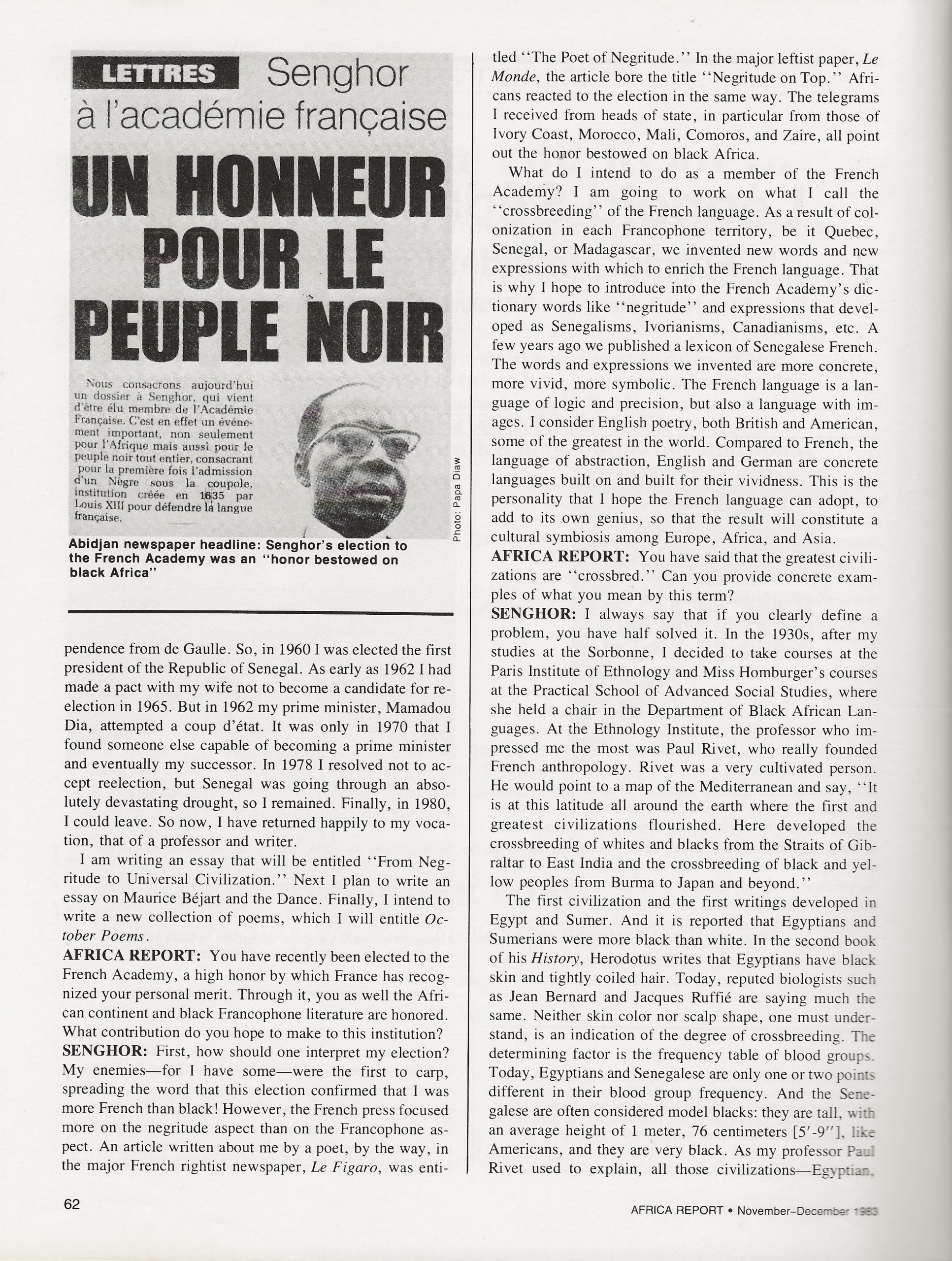

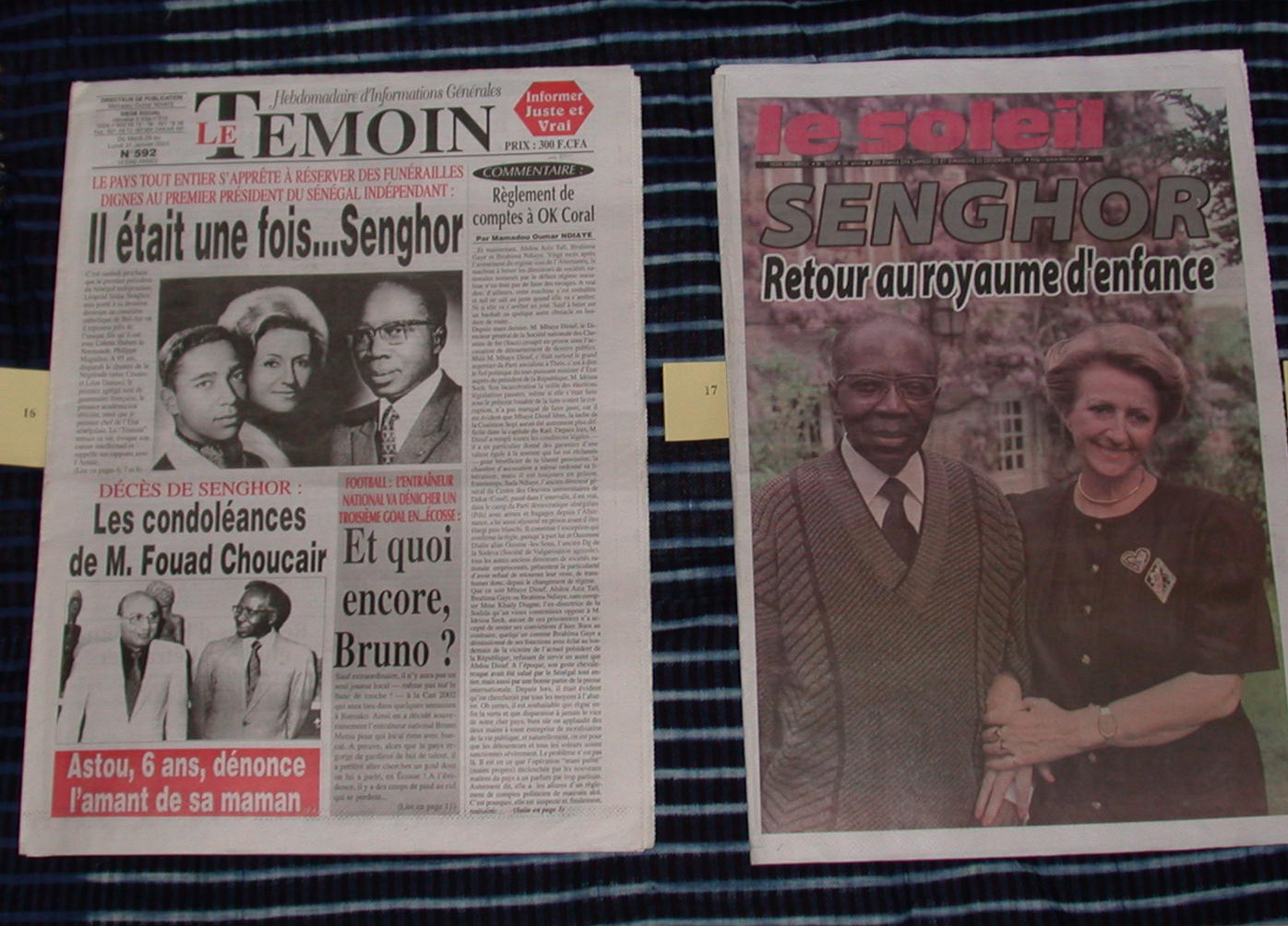

My 1983 Actually, if truth be told, the president was slightly distracted during our discussion. The day before, the daily newspaper from Ivory Coast, Fraternité-Matin, had printed a front-page above-the-fold article on Senghor’s having been elected a member of the prestigious Académie française, the French Academy in Paris. I probably could not have brought him a more desired house present. You will notice it in four of the 24 images accompanying this article. The main headline was CACAO (cocoa), but no. 2 was Senghor’s academic honor. There was often a rivalry between the presidents of

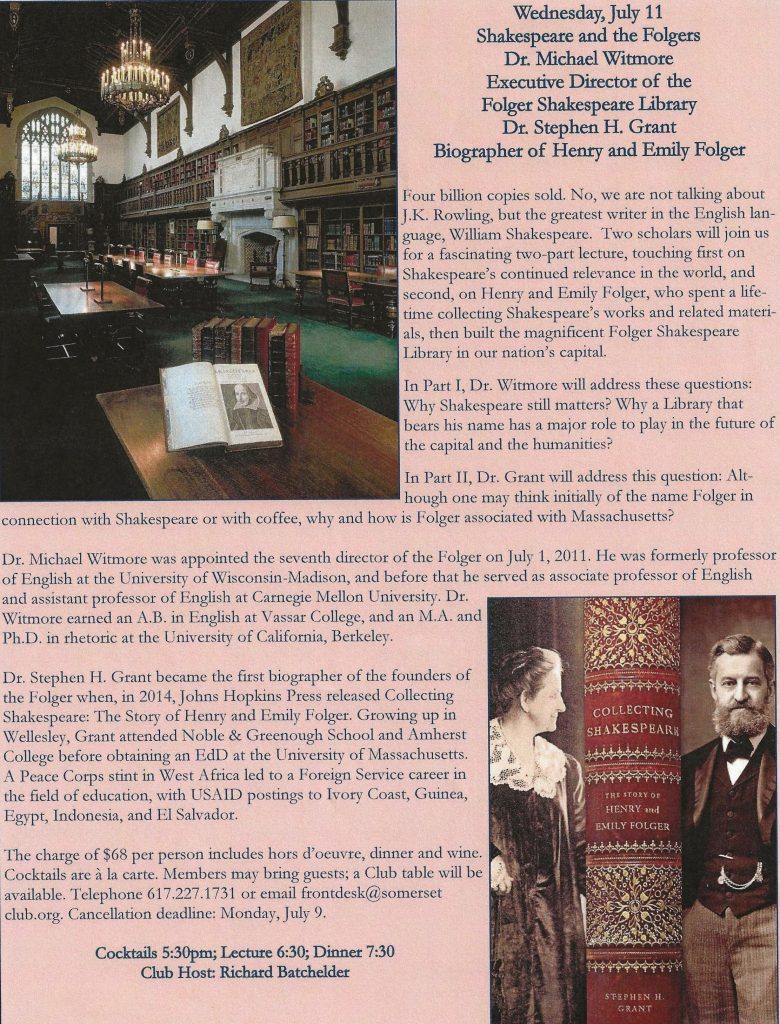

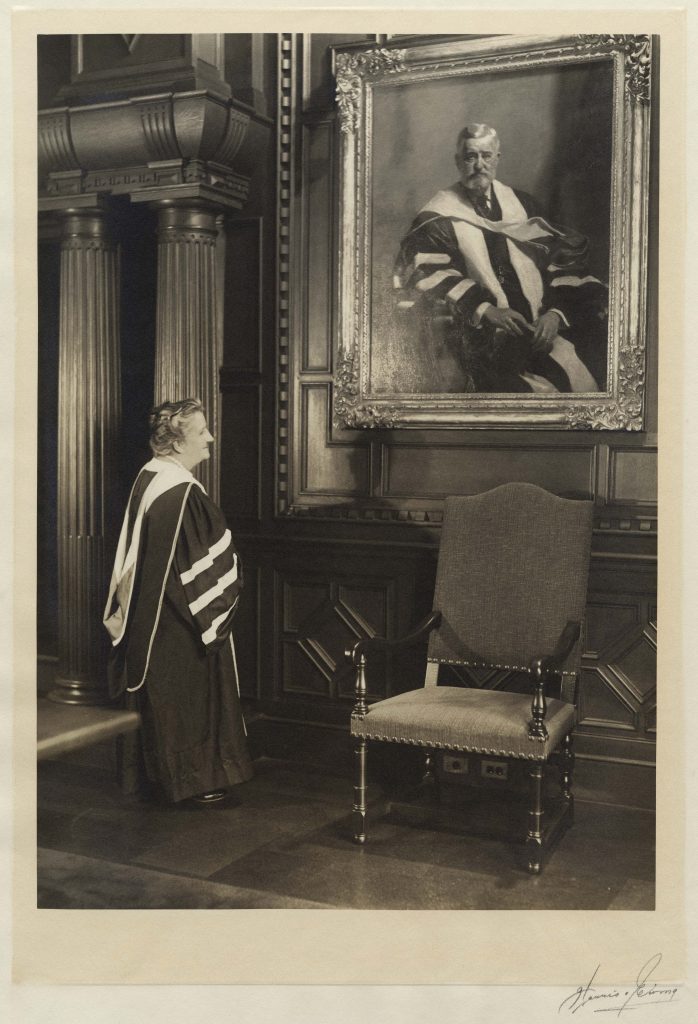

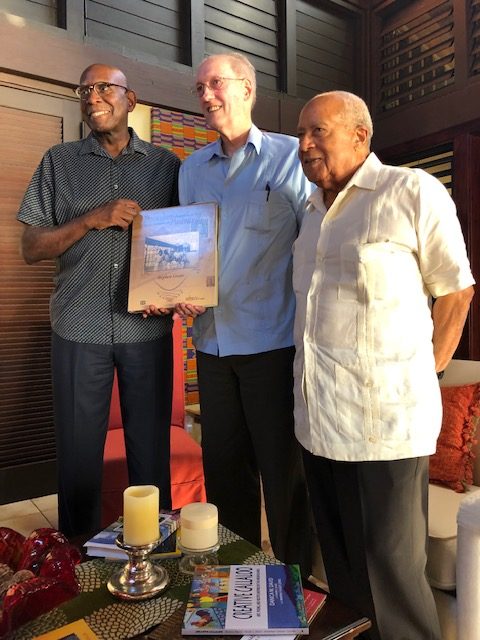

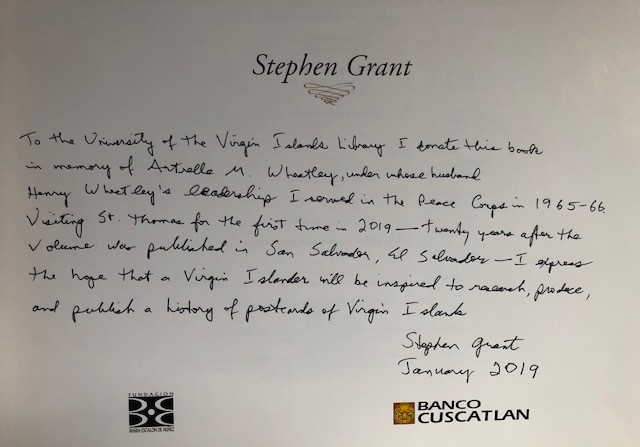

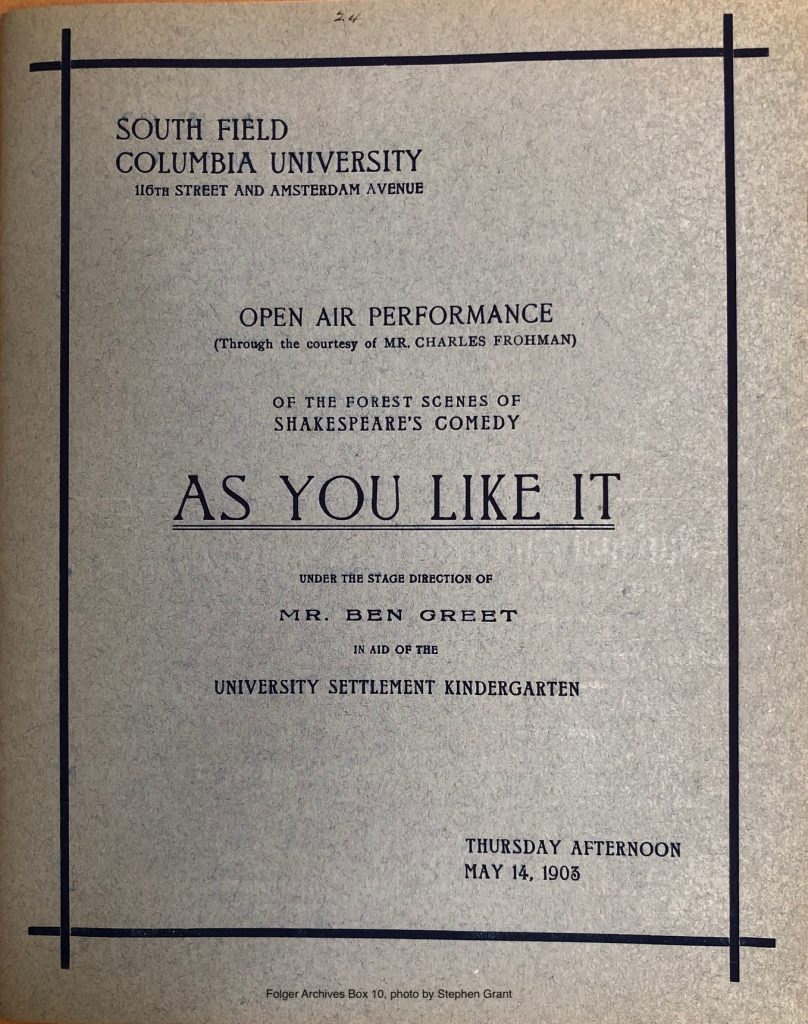

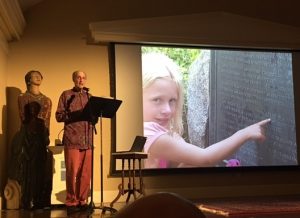

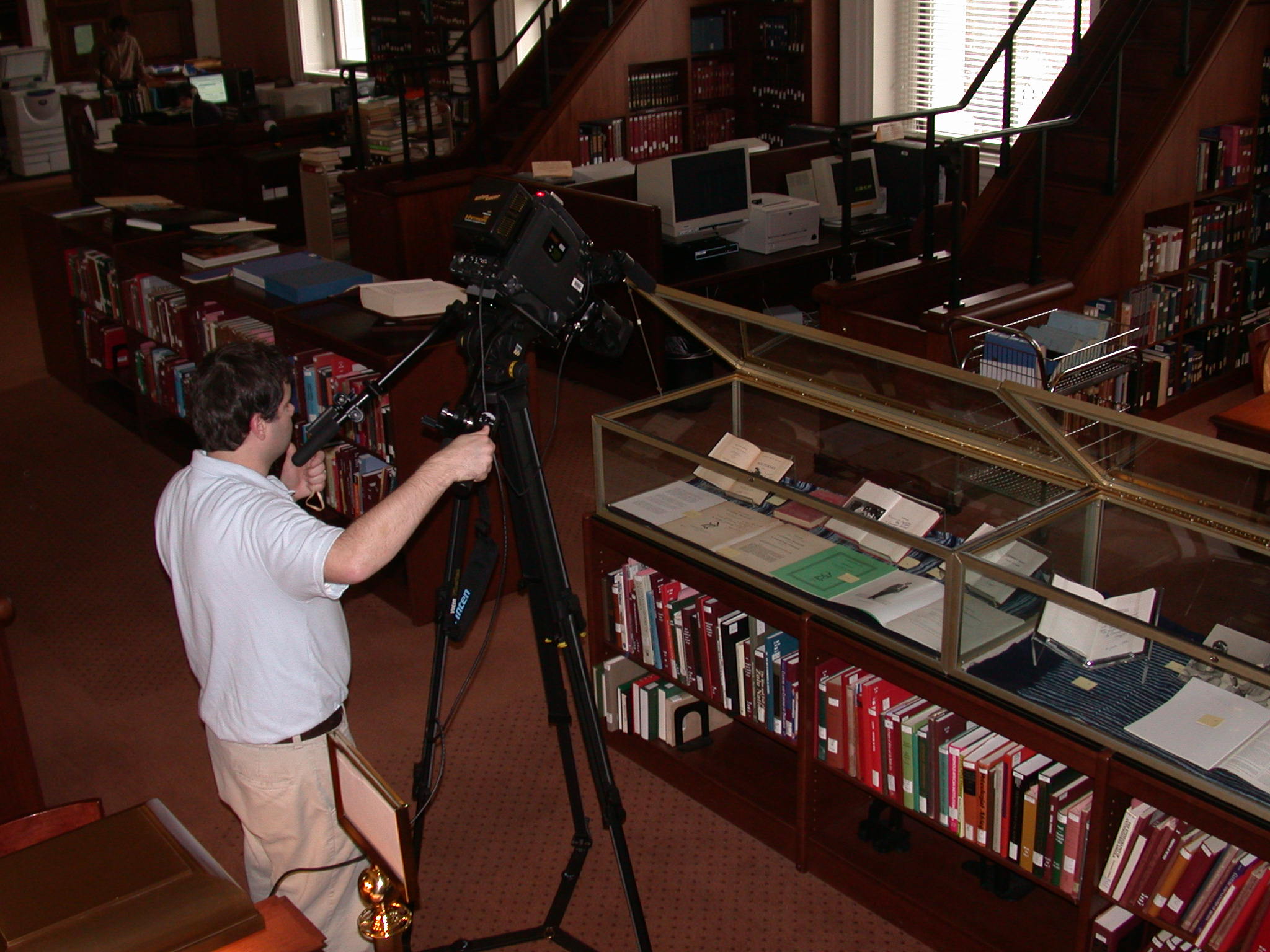

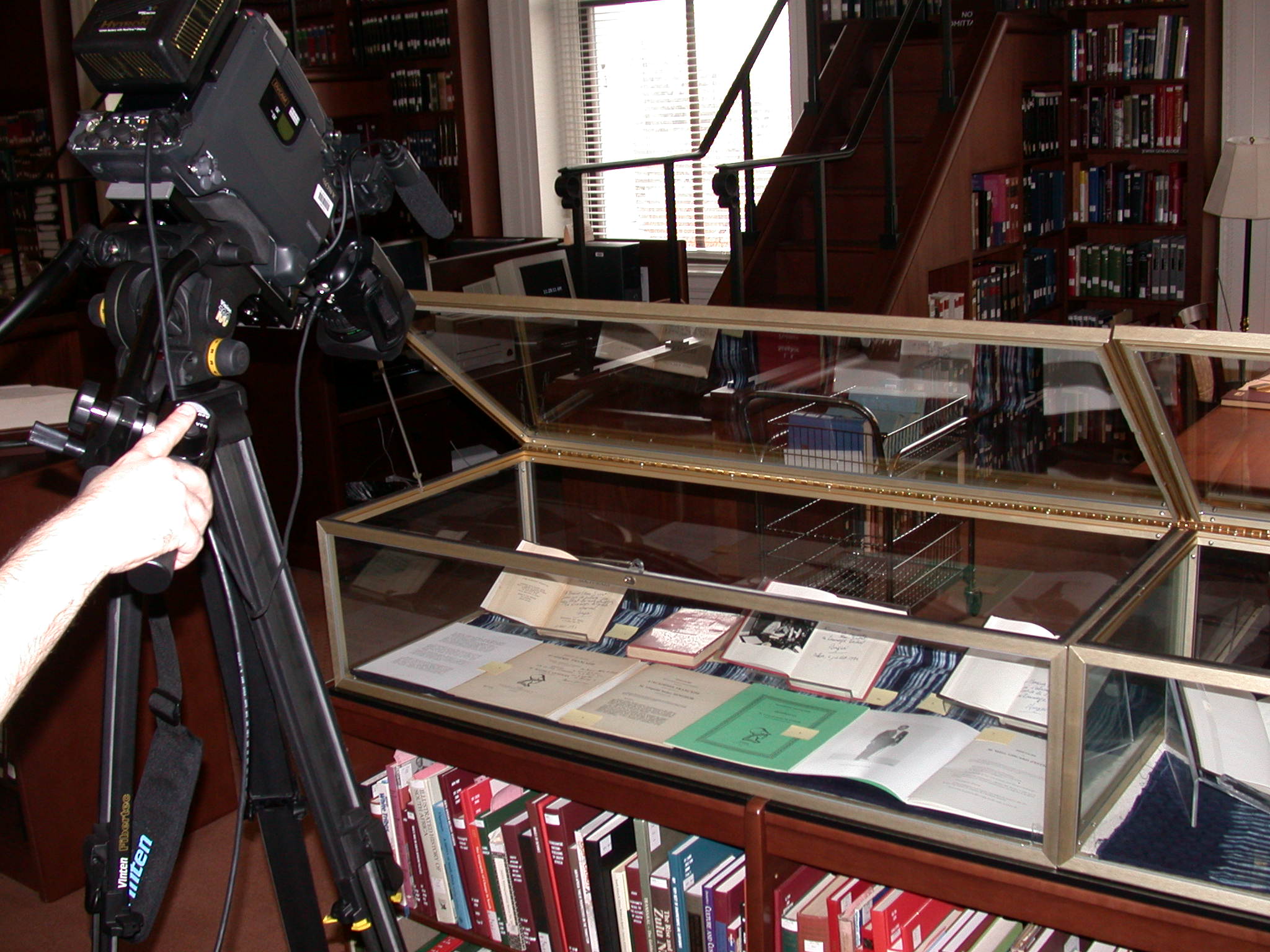

Actually, if truth be told, the president was slightly distracted during our discussion. The day before, the daily newspaper from Ivory Coast, Fraternité-Matin, had printed a front-page above-the-fold article on Senghor’s having been elected a member of the prestigious Académie française, the French Academy in Paris. I probably could not have brought him a more desired house present. You will notice it in four of the 24 images accompanying this article. The main headline was CACAO (cocoa), but no. 2 was Senghor’s academic honor. There was often a rivalry between the presidents of On Nov. 7, 2006, the Library of Congress welcomed visitors to the African & Middle Eastern Division (AMED) Reading Room to view an exhibit I assembled to commemorate 100 years since the birth of Léopold Sédar Senghor.

On Nov. 7, 2006, the Library of Congress welcomed visitors to the African & Middle Eastern Division (AMED) Reading Room to view an exhibit I assembled to commemorate 100 years since the birth of Léopold Sédar Senghor.

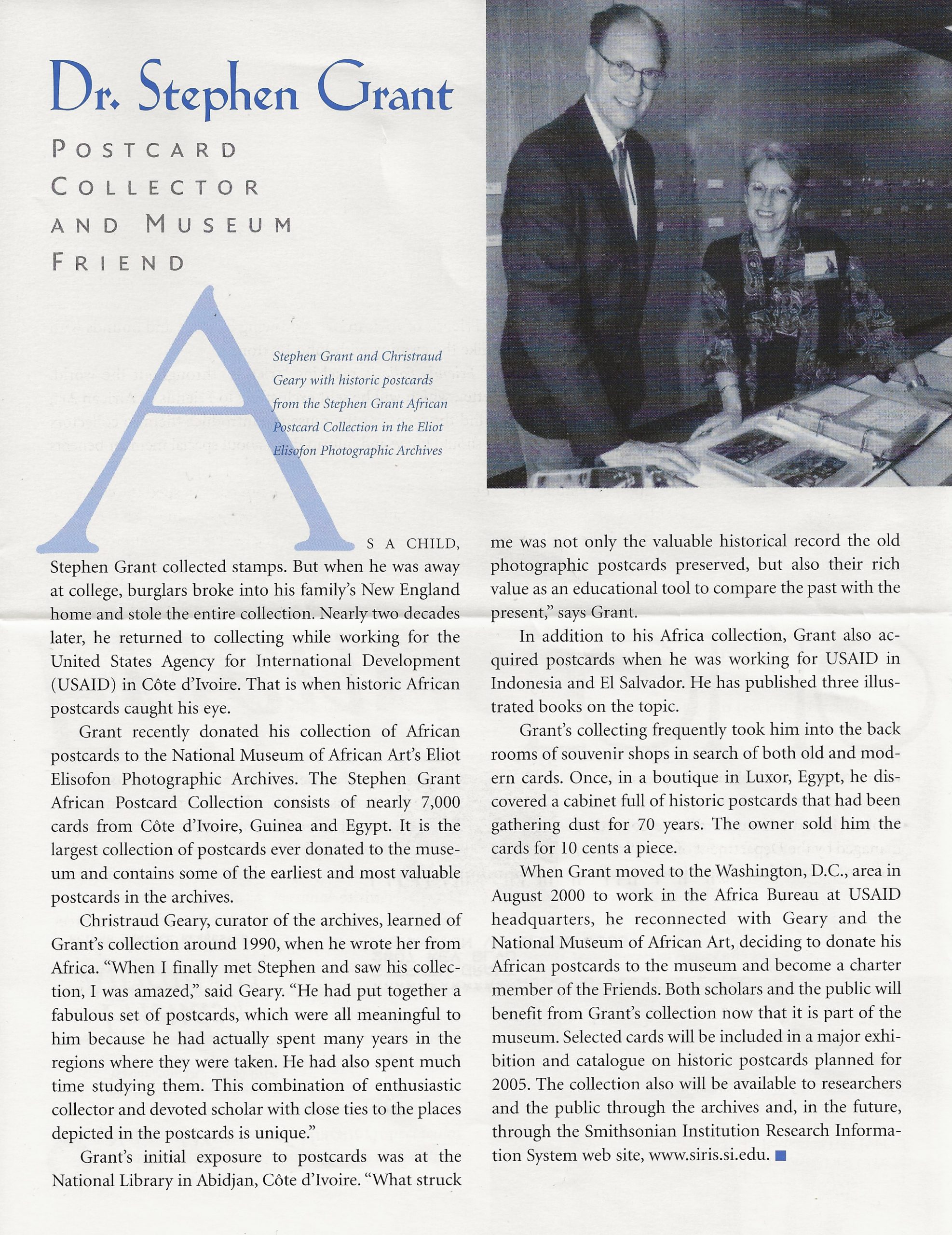

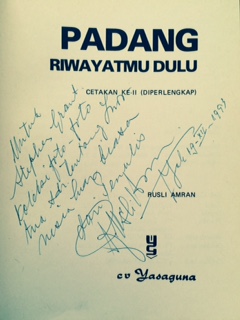

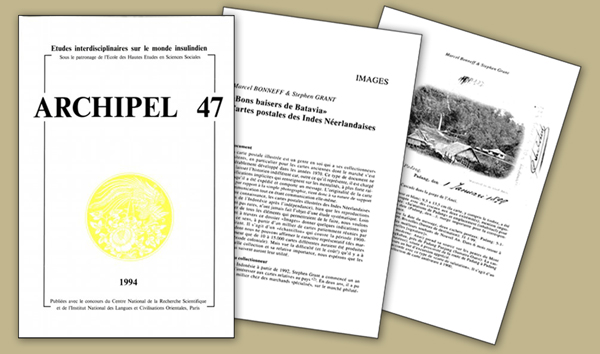

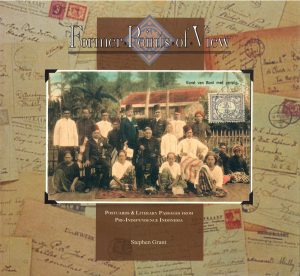

The present bulletin cover article by

The present bulletin cover article by

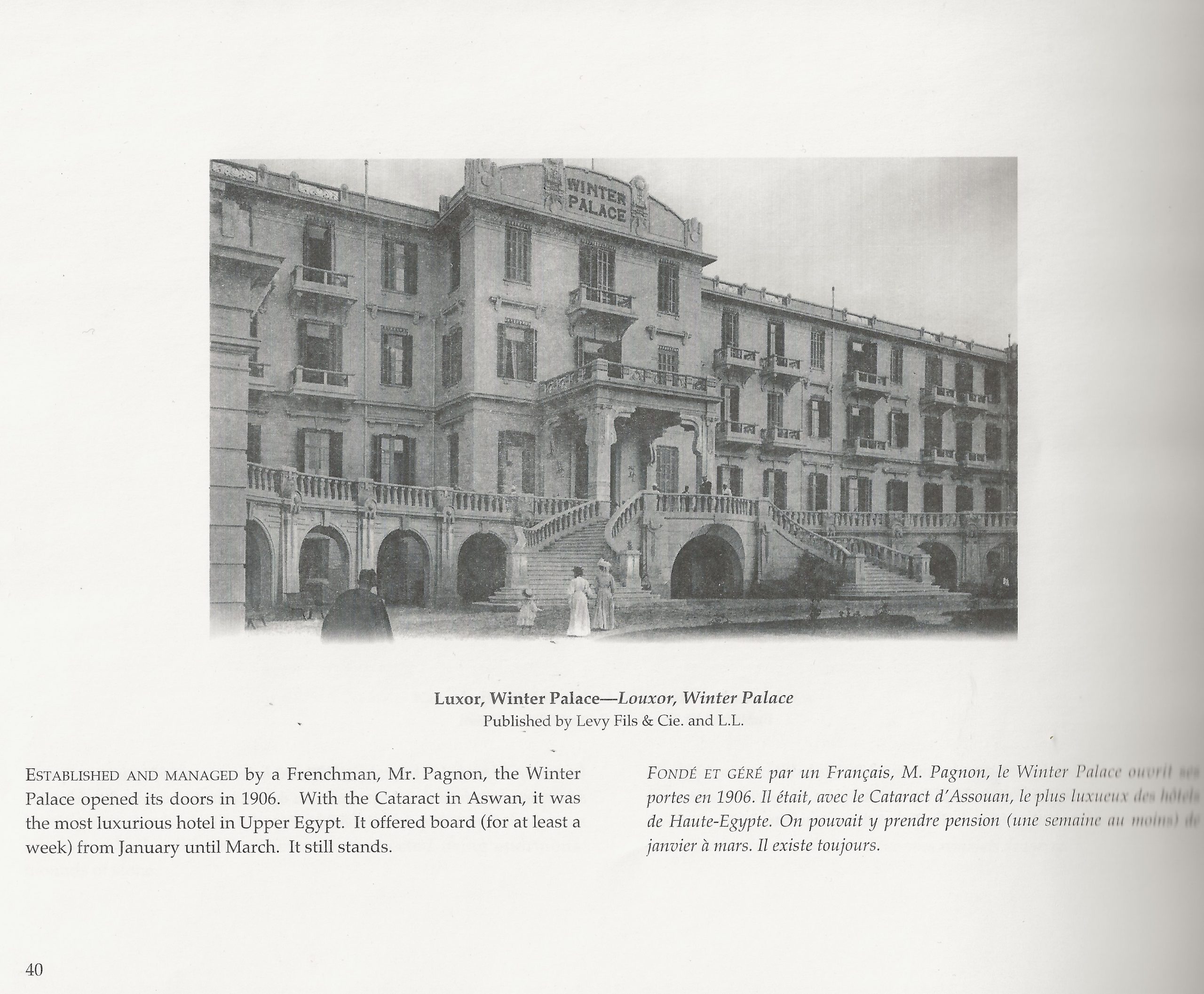

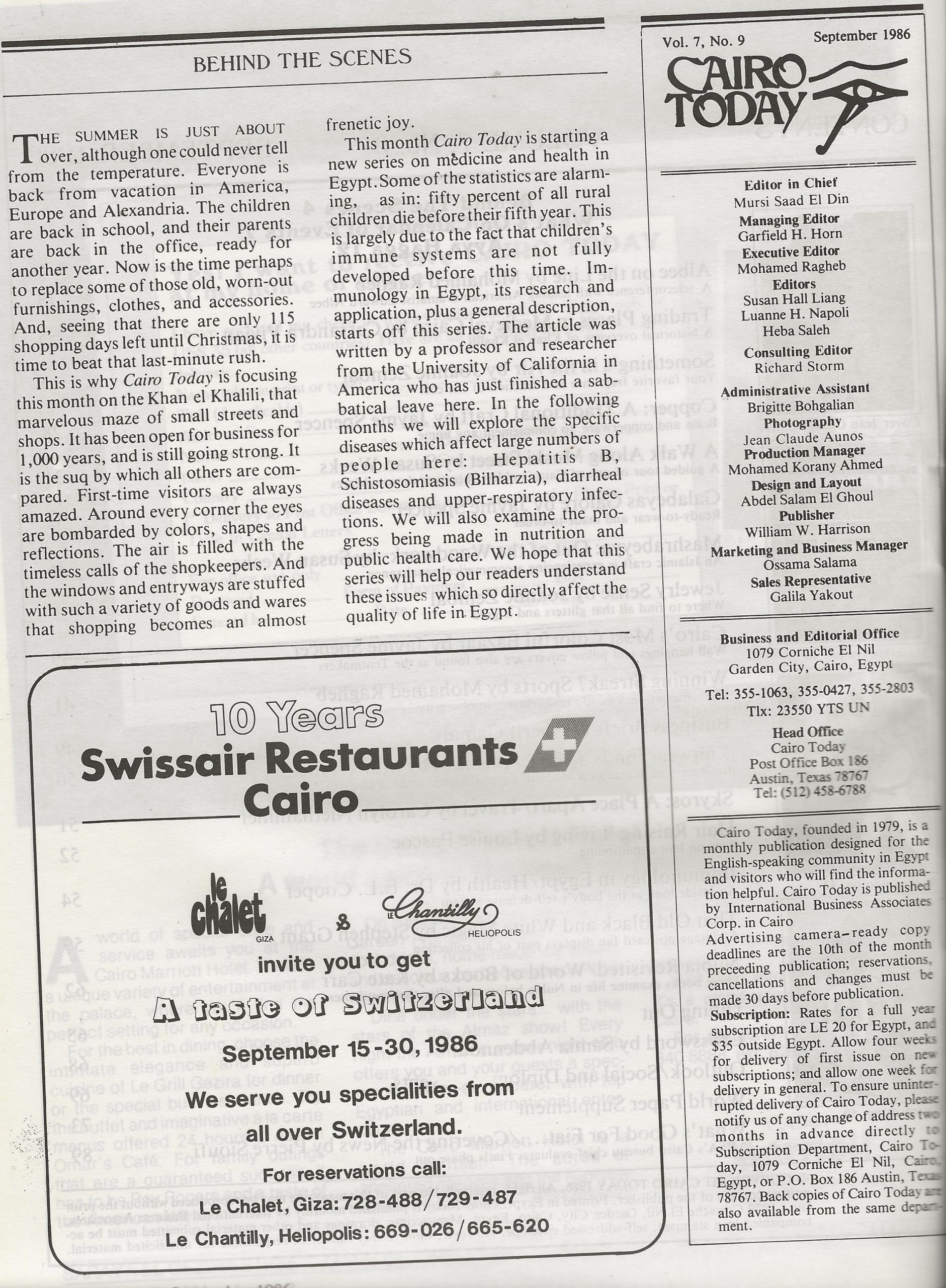

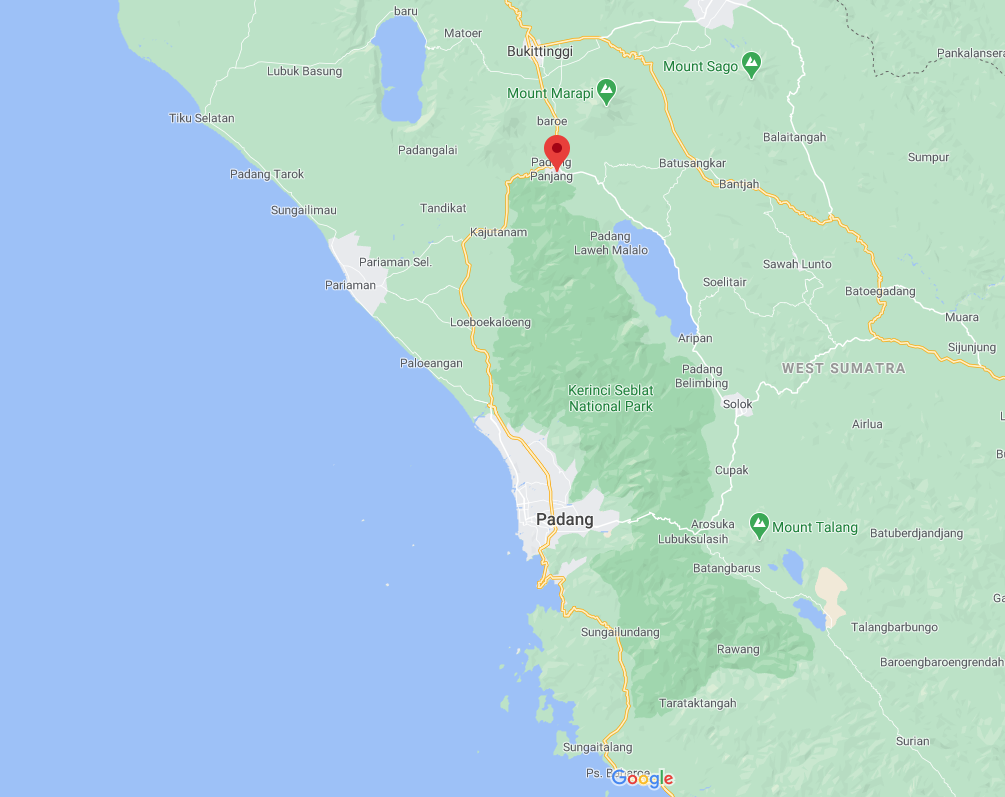

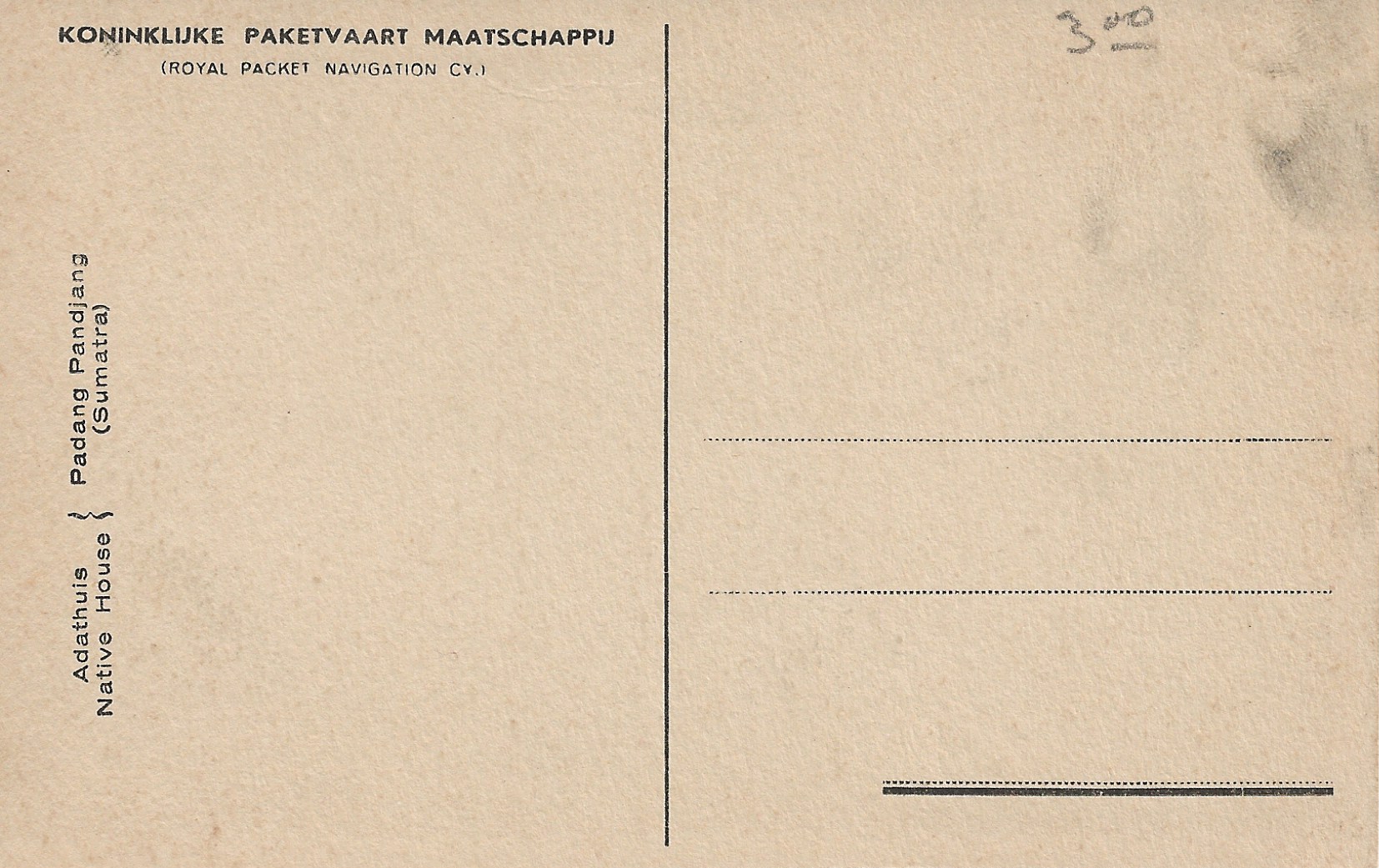

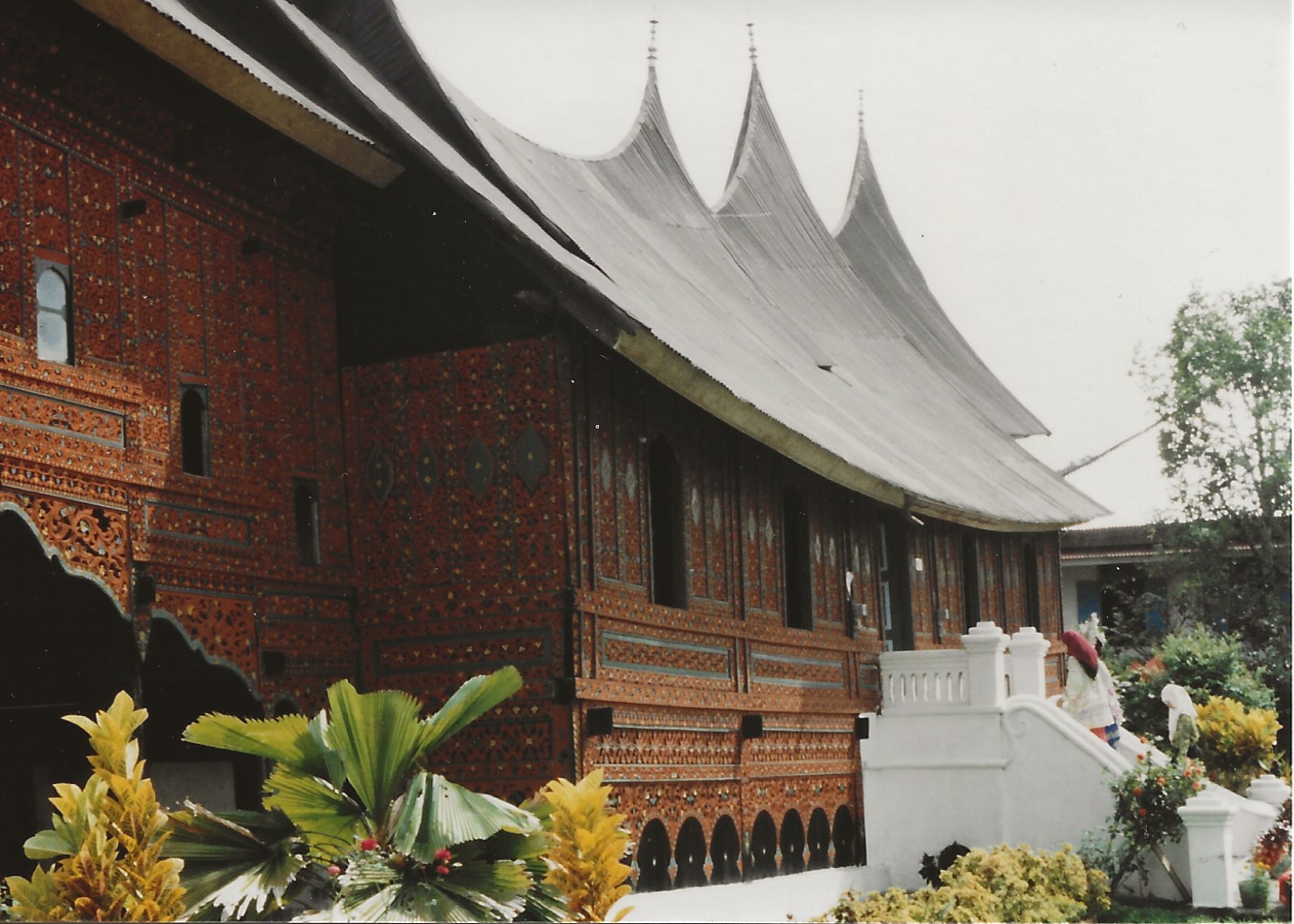

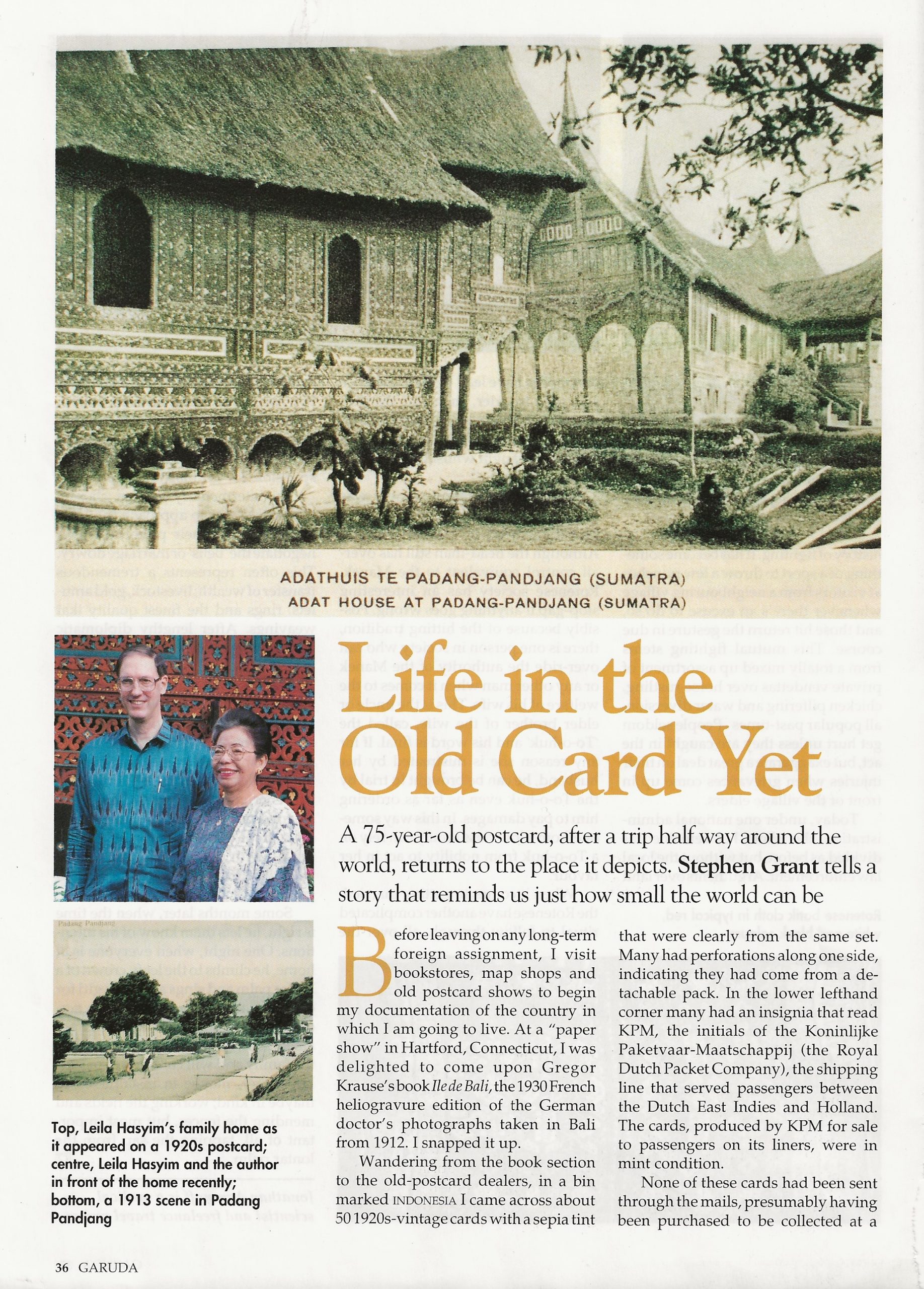

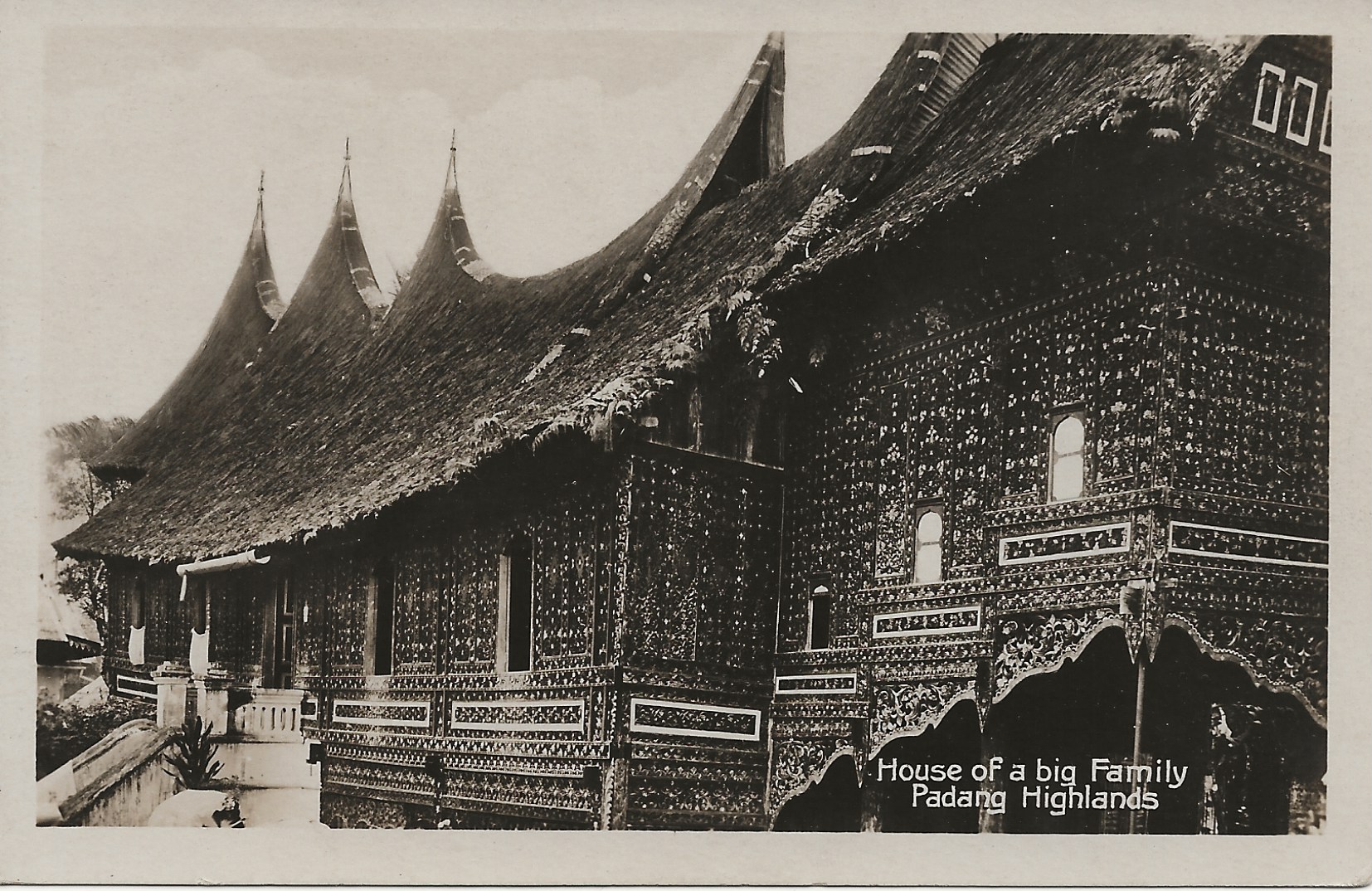

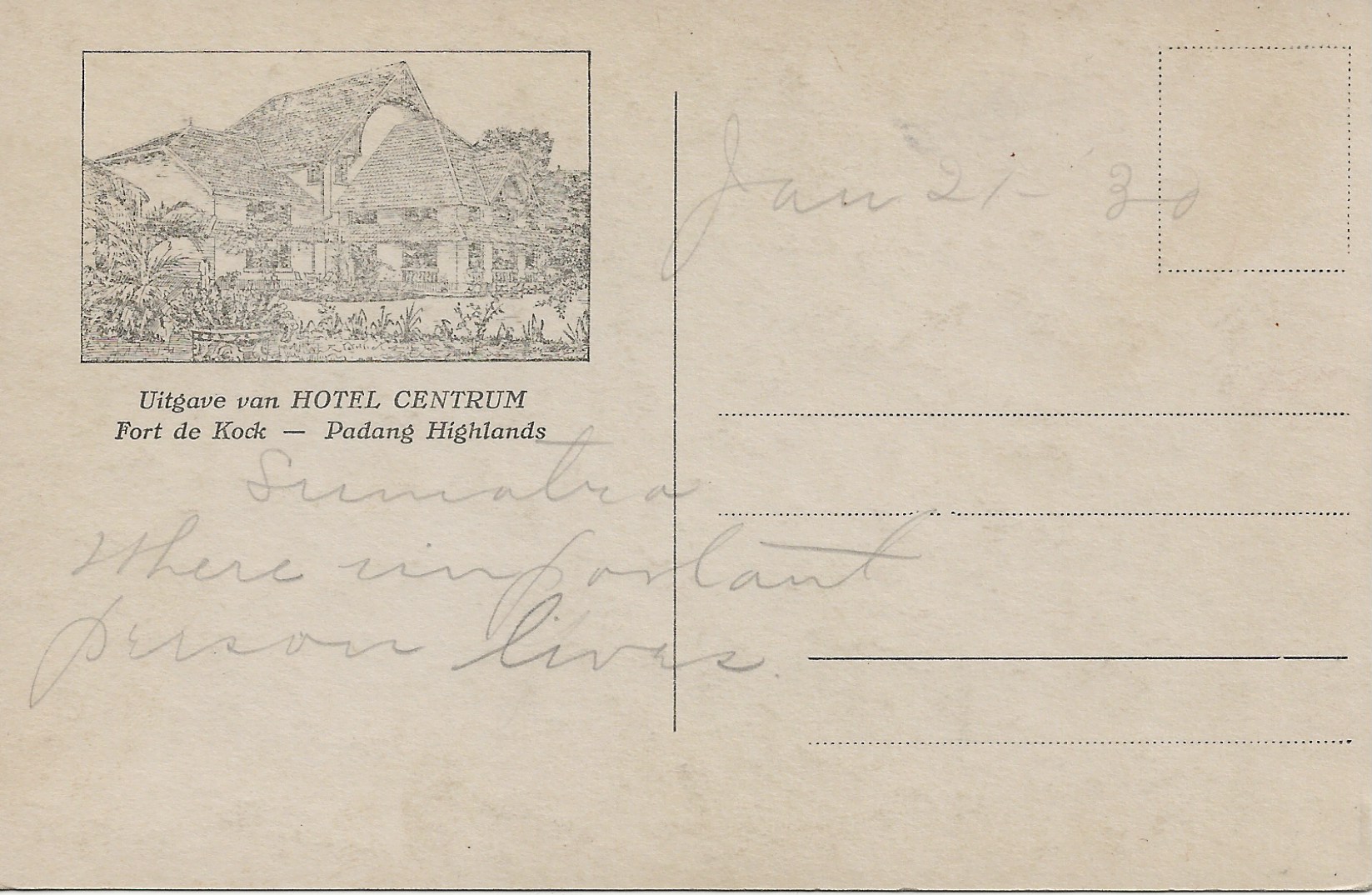

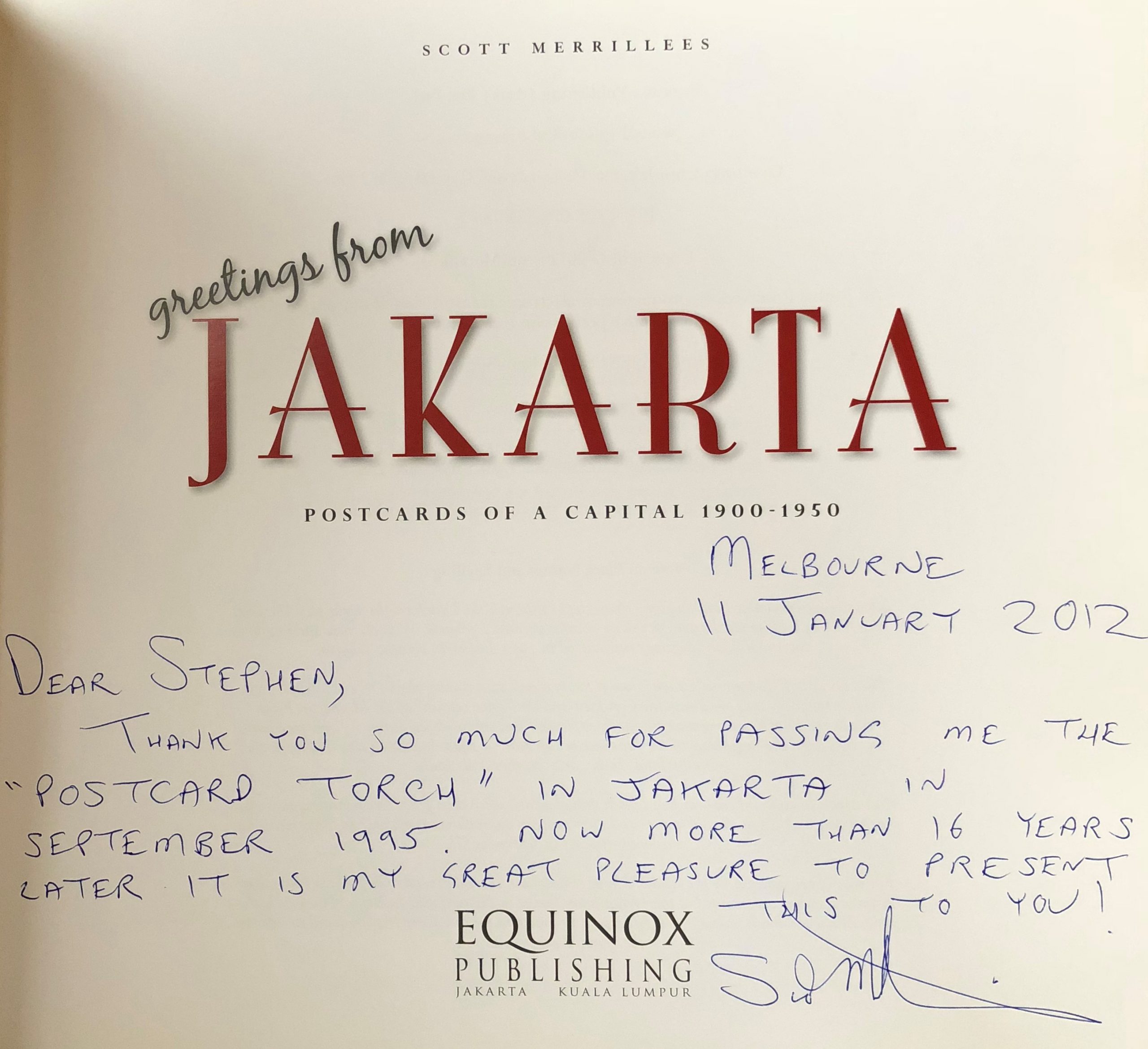

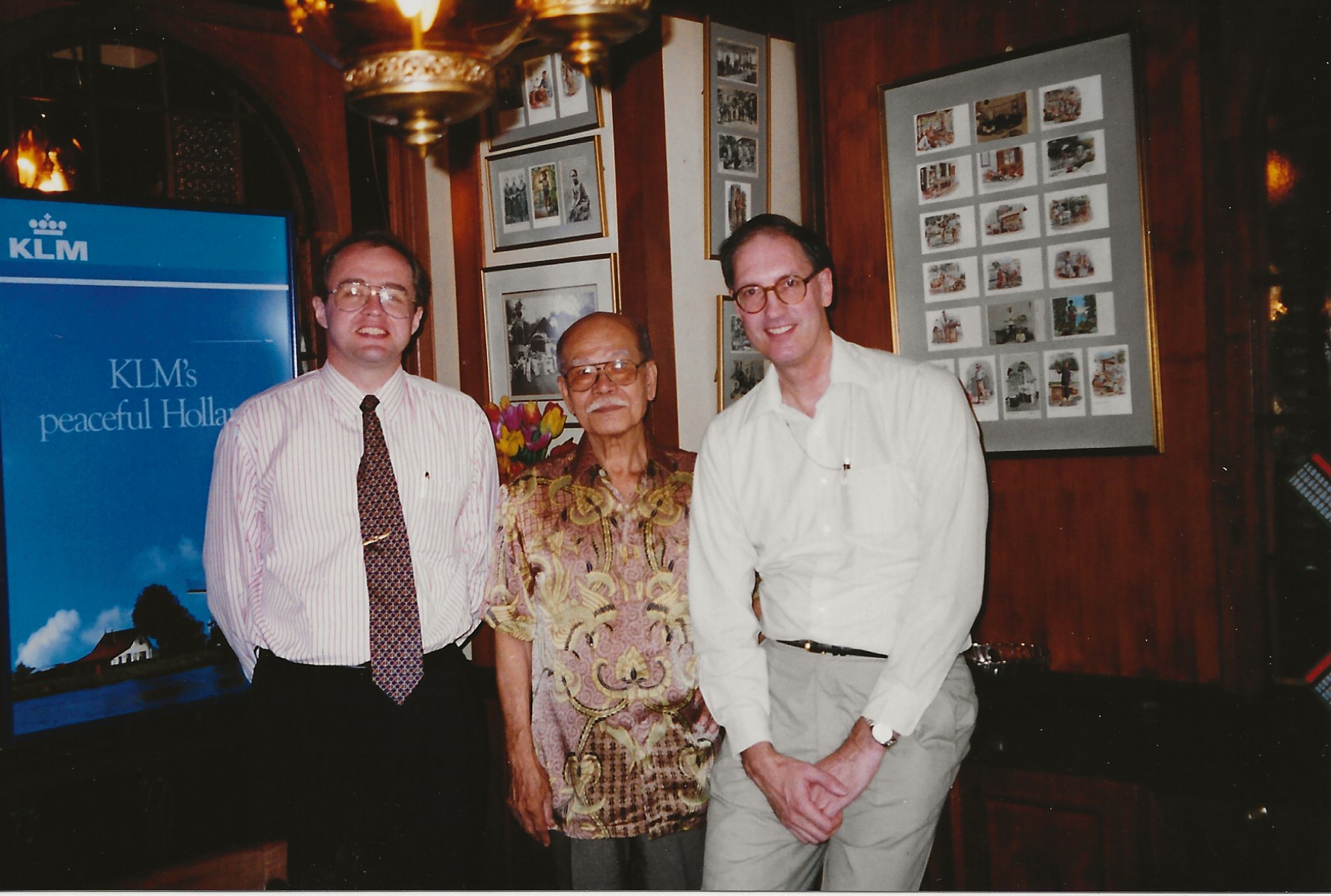

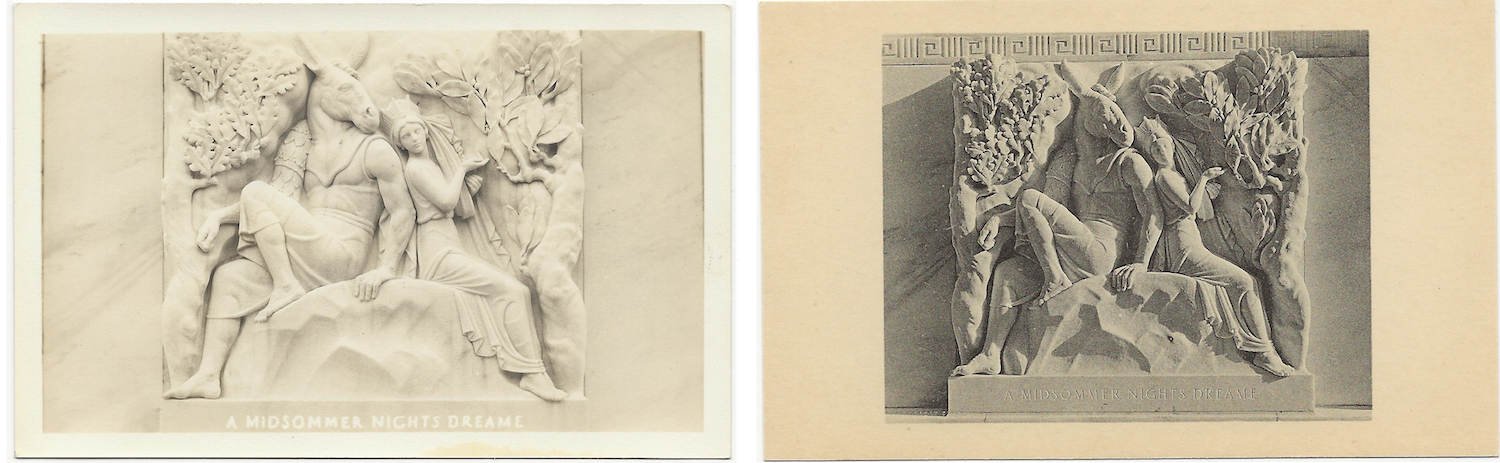

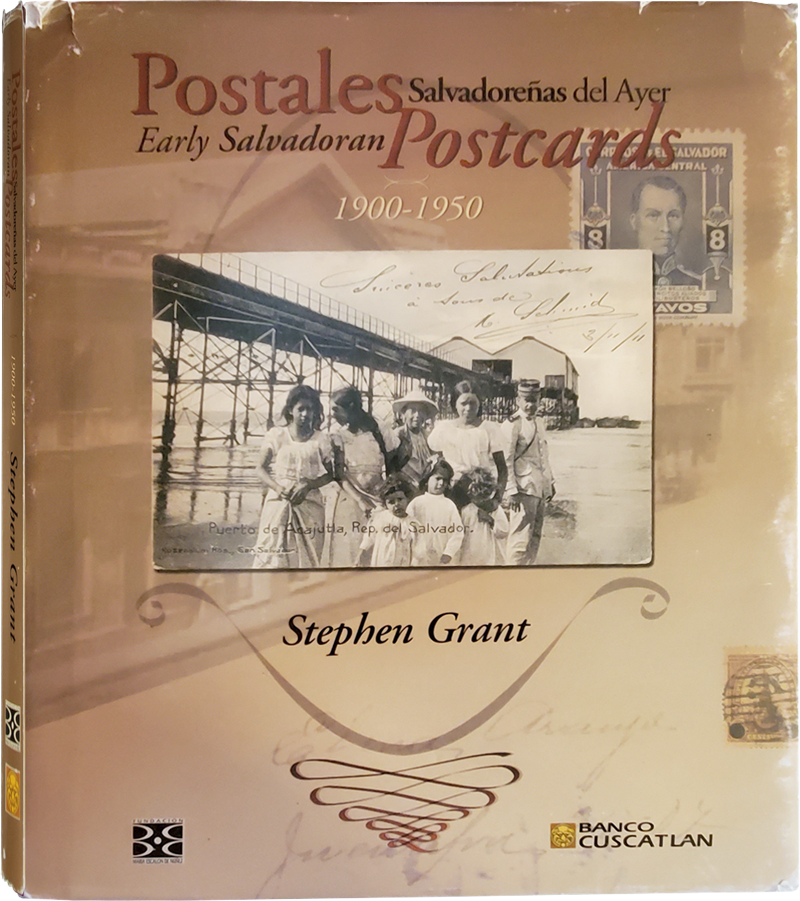

One day in Bandung on the Indonesian island of Java, I handed my language instructor, Ibu Leila Hasyim, a pack of sepia postcards, thinking she could teach me some new vocabulary as we together examined the vintage photos on them.

One day in Bandung on the Indonesian island of Java, I handed my language instructor, Ibu Leila Hasyim, a pack of sepia postcards, thinking she could teach me some new vocabulary as we together examined the vintage photos on them.