The subject of this blog post is an historic building in downtown San Salvador, the capital of El Salvador in Central America. I lived and worked in San Salvador during the last four years of the millennium. It’s the only building I’ve ever been in that has 116 balconies and 414 doors. Here’s what it looks like today from the outside.

Fig. 1. Palacio Nacional, San Salvador, El Salvador

We learn from Wikipedia that “The building contains four main rooms and 101 secondary rooms; each of the four main rooms has a distinctive color. The Red Room (Salon Rojo) is used for receptions held by the Salvadoran Foreign Ministry, and the ceremonial presentation of ambassadors’ credentials. It has been used for ceremonial purposes since the administration of General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez. The Yellow Room (Salon Amarillo) is used as an office for the President of the Republic, while the Pink Room (Salon Rosado) housed the Supreme Court and later the Ministry of Defense. The Blue Room (Salon Azul) was the meeting place of the Legislature of El Salvador from 1906. The room is now called the Salvadoran Parliament in commemoration of its former purpose, and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1974.”

Fig. 2. Captain General Gerardo Barrios, President of El Salvador 1859–1863

During the presidency of Captain General Gerardo Barrios (1813–1865) in El Salvador, from 1860 to 1863, the idea to build a National Palace was born. The original National Palace was built between 1866 and 1870 by José Dolores Melara (1847–1884) and Ildefonso Marín (?–1871). The exterior was in masonry on the first floor and wood and stamped sheet metal on the second floor.

The first test of its solidity came in 1873, during the San José Earthquake. A total renovation was required, which was terminated in 1875. The palace perished in 1889 by arson. In the calamity disappeared not only the largest and most elegant structure in El Salvador, and also the national and federal archives stored on the first floor. After the fire, the artillery garrison and military police station were temporarily established on the grounds of the palace.

The design of the second National Palace was the work of the Salvadorans, José Emilio Alcaine (1866–1963) and Pascacio Gonzáles Erazo (1848–1917). Construction began in 1905 under President Pedro José Escalón (1847–1923). Responsable for the supervision of the construction was the Salvadoran writer and General, José Maria Peralta Lagos (1873–1944). The Italian engineer Alberto Ferracutti (1875–1966) installed the wide, imposing stairways. The building was inaugurated in 1911 by President General Fernando Figueroa (1852–1919).

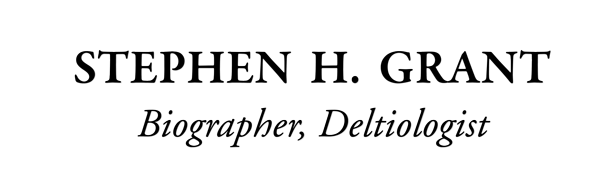

Fig. 3. General Fernando Figueroa, President of El Salvador 1907–1911

The style is French and Italian Renaissance, with Roman arches as well as Greek influences, with Ionic columns on the first floor and Corinthian on the second. The main materials used in the construction were imported: marble and pink granite from Italy; stamped sheet metal and crystal chandeliers from Belgium; and metal beams from Germany. There are four entryways to the building, which contains 116 marble balconies and 414 doors. Much of the work was contracted in Europe, but skilled Salvadoran laborers did the interior decorative work in moulded plaster. The false ceilings were all of imported sheet metal, painted in El Salvador with intricate designs. The edifice was solid enough to withstand seismic disturbances in 1915, 1917, 1919, 1965, and 1986.

Now let’s introduce the postcards! In Fig. 4., the building is facing Bolívar Park (now Barrios Plaza). The building seen to the right is the National Treasury. The photographer is standing in the middle of the Avenida Cuscatlán (now Avenida España-Cuscatlán).

Thr honor guard in dress whites most likely signifies the president is about to enter or leave the palace. He traveled in a horse-drawn carriage called a « Victoria, » visible in the center, imported into El Salvador around 1915. The black vehicle, which lacks a license plate in the rear, may be a 1931 Ford Phaeton. It also might have been used to bring a visiting head of state or other dignatary to the palace. On the lower palace steps several men in dark uniforms are saluting.

Fig. 4. Postcard of the National Palace, Historic Center of San Salvador c1932

Source: Postales Salvadoreñas del Ayer/Early Salvadoran Postcards, p95

Fig. 5. Reverse side of postcard Fig. 4. c1932

Source: Postales Salvadoreñas del Ayer/Early Salvadoran Postcards, p97

In Fig. 5., the word « DEFENDER » written in capitals on the reverse side of postcards indicates that the photo paper was produced in the United States by the Dupont Company. The DEFENDER logo on this card was used from 1920 to 1940. Since we have no postmark or message including the date, I have to guess ; I’ll say c1932.

Uses of the palace have changed over the years. From the 1920s until the 1980s, the palace housed the legislature, the Supreme Court, and various government ministries. It was used for diplomatic receptions and popular dances. Since 1987, the Ministry of Education through the « Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y el Arte (CONCULTURA) » has been restoring the palace, a monumental task.

Fig. 6. National Palace Façade with Statue of Christopher Columbus 1998

Two statues are visible on either side of the central portico of the palace. They represent Christopher Columbus and Queen Elizabeth of Spain, and were gifts from the Spanish King Alfonso XIII in 1924.

Fig. 7. Norfolk pine trees in central courtyard of National Palace

Towering over the National Palace are five Norfolk Pines planted to represent the five states that established themselves on July 1, 1823 as the United Provinces of Central America: El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. You see the pines also in Fig. 1.

Now we turn to the main postcard featured in the article. While the previous postcard was « postally unused » or « unposted » in the jargon (never sent through the mail), this one was « postally used. » I prefer acquiring postally used cards, for you have have a chance for a four-in-one: a picture, a message, a postage stamp, and a postmark. The story-telling possibilities are greatly enhanced.

Fig. 8. Postcard of Congressional Hall of National Palace 1912

Source: Postales Salvadoreñas del Ayer/Early Salvadoran Postcards, p99

The title of this postcard is, « Palacio Nacional, Salón del Congreso, San Salvador. » Under the title on the card is the handwritten date, July 12, 1912, that the postcard was sent from San Salvador to Havana, Cuba. Notice the unusual way the year 1912 is abbreviated, « 912. » This postcard was sold by the Librería y Papelería Moderna in San Salvador, founded in 1883.

This room was referred to either as the « Salón del Congreso » (Congressional Room), or as the « Salón Azul » (Blue Room). It is where the National Assembly deliberated. The room also served for the swearing in of new presidents. It was located on the second floor of the National Palace inaugurated in 1911. This room faced the 1a Avenida Sur, that is, west. The interior colors were, reportedly, blue, white, and gold. The Blue Room is where the coffin of assassinated President Dr. Manuel Enrique Araujo (1865–1913) lay in state for two days.

Fig. 9. Dr. Manuel Enrique Araujo, President of El Salvador 1911–1913

Fig. 10. Photographer interested in 1912 postcard of Congressional Hall of National Palace

I put on several exhibits of my collection of Salvadoran postcards in San Salvador, notably at the American Embassy and the Museo Nacional de Antropologia Dr. David. J. Guzman. Fig. 10. shows a Salvadoran photographer who came to my home in San Benito to photograph this very postcard. What he did with the photo I never heard. Creatively, he achieved the desired angle with my embroidered pillows from Ivory Coast.

It is fairly rare to see an interior scene on picture postcards. It is all the more of historical interest to see the interior of the legislature in El Salvador, as so few people had access to this room, or could even imagine what it looked like. A warning about the color, however, The photograph was taken originally in black and white. Later color was added through a process of « hand tinting » before the postcard was mass produced. The colors are do not necessarily reflect the original colors.

Although « Nando’s » last name is not written anywhere on this postcard, I found out what it is: Gallegos. In 1997, I acquired in France an important collection of postcards which had been sent from San Salvador over the period 1900–1914 with the complete name Fernando Gallegos, to two sisters named « Bousquet » in Havana, Cuba.

I tried to find out whether there was any record of a Bousquet family in El Salvador. By consulting old newspapers in the National Library in San Salvador, I learned that Pablo Bousquet (d. 1902) was an importer/exporter in San Salvador during the period, 1895–1900. In his store in Plazuela Santa Lucia (today July 14th Square), Pablo sold musical instruments, rugs, perfume, silks, woolens and cottons. hats, and toys. My theory is that the elder Bousquets sent their two daughters to study in Havana. Since « Bousquet » is a French name, I speculate that their family and their many trunks eventually returned from Cuba to France and that is why the cards reappeared in that country 90 years later. In the San Salvador cemetery I located the tombs of Pablo as well as Laura Bousquet and Soledad de Bousquet, who may have been related to the Cuban branch.

The correspondent was Fernando Gallegos (1888–1923). He was one of seven children of Salvador Gallegos Valdés (1844–1919) and Elena Rosales (1862–1926). The father was Salvadoran Minister of Foreign Relations in the 1880s, and also served as ambassador to several European countries. The family lived on the corner of Avenida Cuscatlán and 4a Calle Oriente, diagonally across from the National Palace. Let’s turn the postcard over.

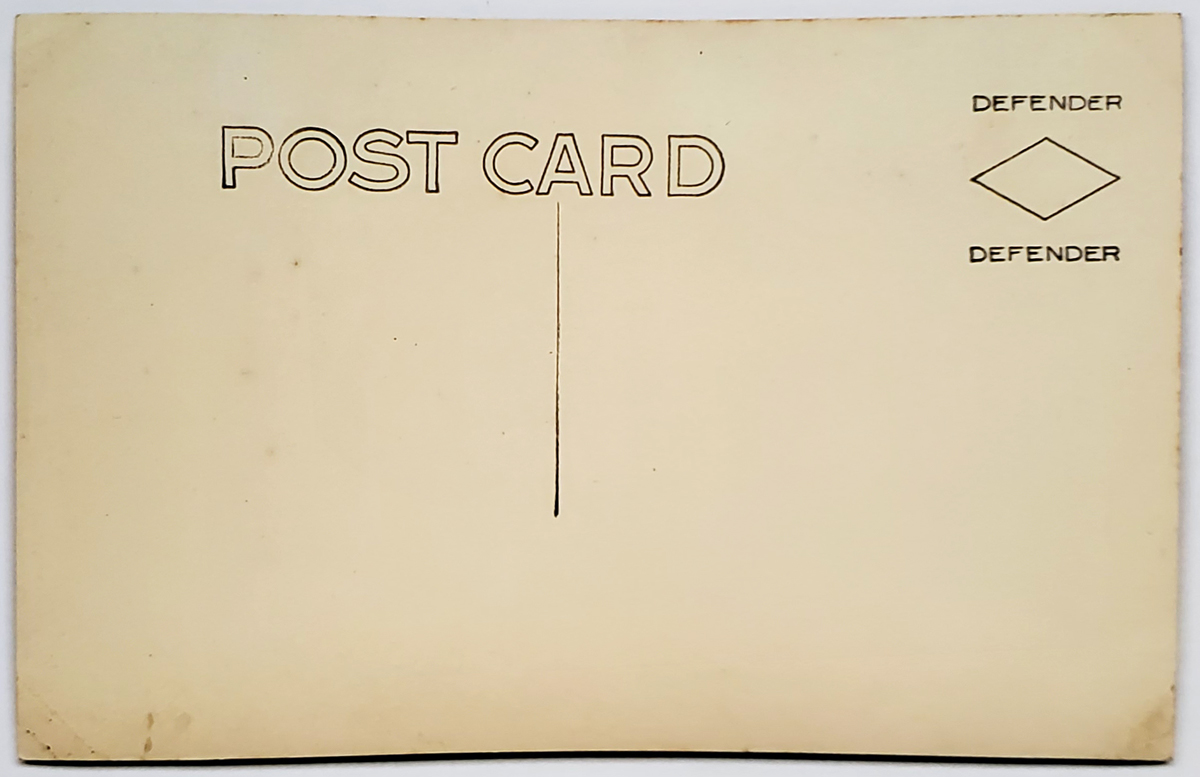

Fig. 11. Reverse side of postcard Fig. 8. 1912

Source: Postales Salvadoreñas del Ayer/Early Salvadoran Postcards, p101

« Amiga mía : Sus anunciadas 5 postales aún no han llegado a mis manos a pesar de que han llegado a este rinconcito tres correos más del exterior. Pero es la intención la que vale, y las dos por recibidas. Ya recibió mis otros envíos ? suyo affmo, Nando. »

« My friend, your announced 5 postcards have not arrived from abroad in this little place despite three more mail arrivals. But it is the thought that counts, and I consider that they are as well as here. Did you receive my other mailings? Your affectionate Nando. »

The message in most of Nando’s postcards centered on the topic of postcard collecting. He clearly was exchanging many postcards with the sisters, and concerned when the mail did not get through. As a postcard collector––or deltiologist––myself, I felt a special kinship with Nando. Some of his messages to the sisters referred to historical and political events in El Salvador; one message was romantic.

During the years of this correspondence, Fernando was a medical student at the University of El Salvador. He never completed his medical studies, however. Some say he hit his head from a fall off a horse. The result was he lost his mind, and was sent to an asylum in California where he died. A family photograph taken in 1915 shows all seven Gallegos children, with the exception of Fernando. Since the latest postcard in my collection that he sent dates from June 1914, it is thought that sometime in 1914–1915 he suffered his infirmity and was sent to the United States.

Figs. 2., 3., and 9. are close-up photos that I took of three Salvadoran presidents whose portraits are displayed in the Red Room. In Fig. 12., I give you an idea of the elaborate setting for the presidential portrait gallery.

Fig. 12. Presidential portrait gallery in Palacio Nacional

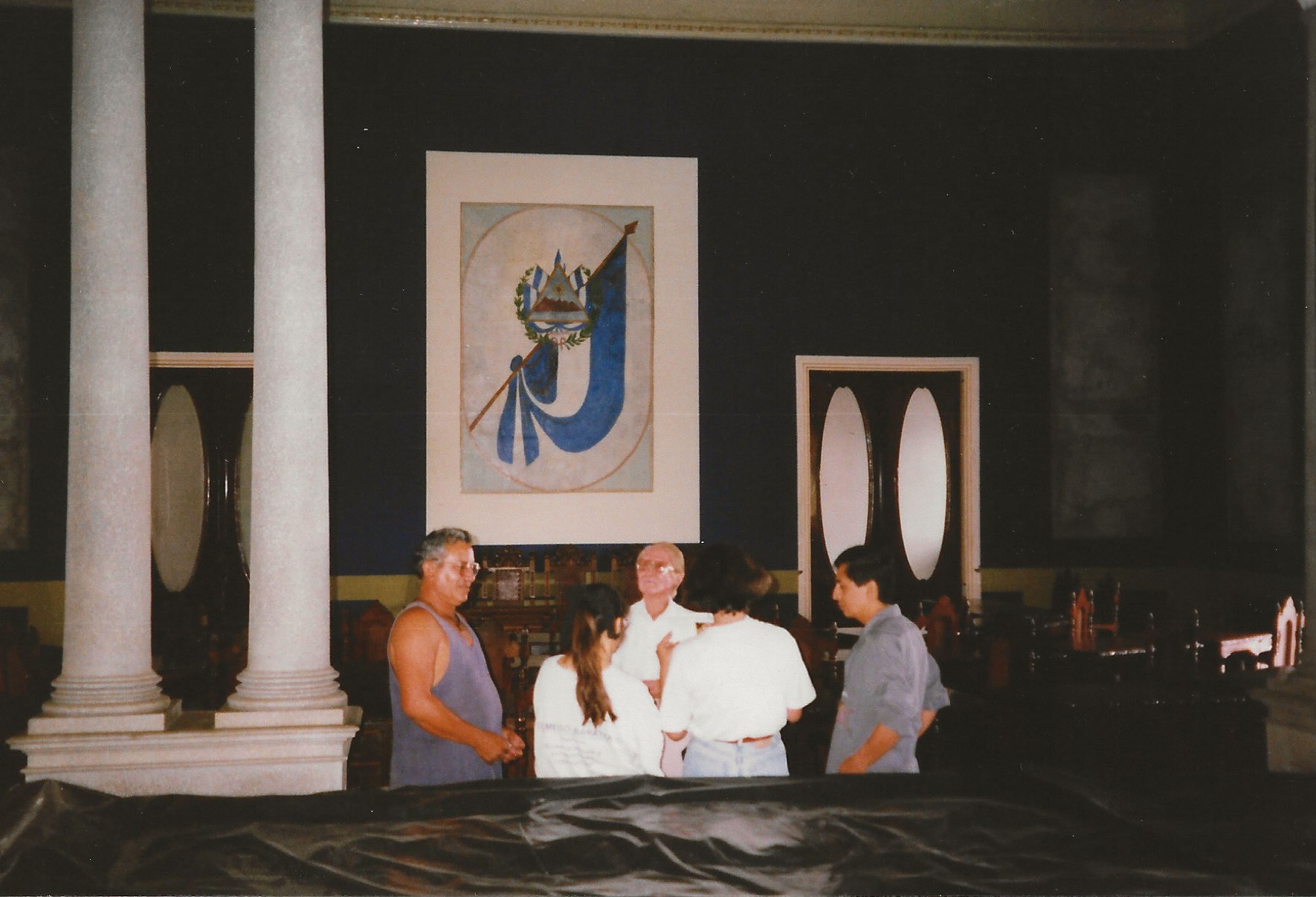

The Blue Room was being restored (in 1998) by CONCULTURA.

Fig. 13. Restoration crew a 1998

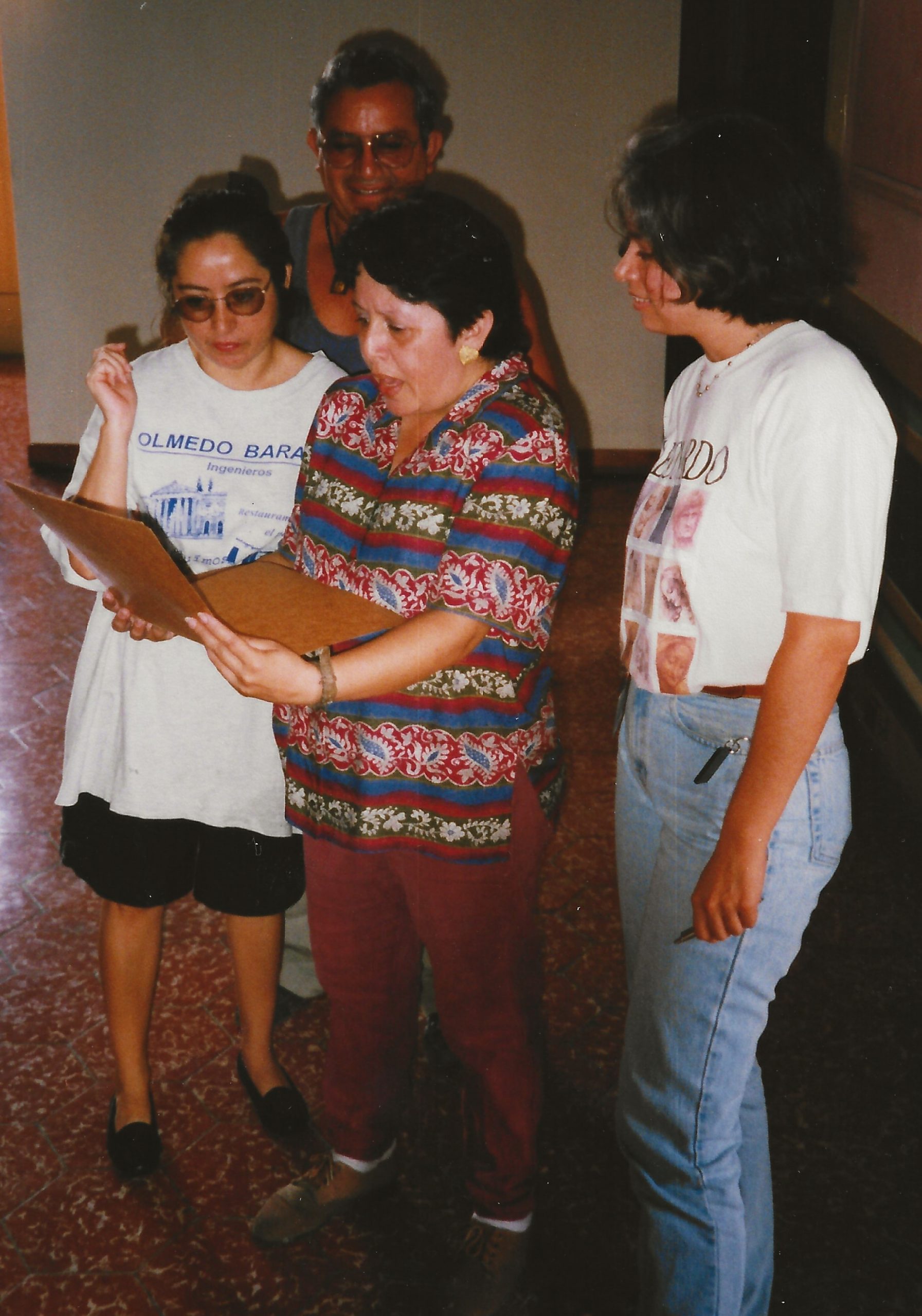

Fig. 14. Restoration crew b 1998

The restoration crew offered to take me around, first by showing me rooms where both walls and ceilings were in dire need of repair.

Fig. 15. Damaged ceiling awaiting renovation 1998

Fig. 16. Damaged wall awaiting renovation 1998

Then they took me to admire the restorations. The difference was stunning.

Fig. 17. Repaired wall and ceiling during renovation 1998

Fig. 18. Blue Room repaired a

Fig. 19. Blue Room repaired b

One of the crew pointed out to me the intertwined gesso « S » and « A » for Salón Azul.

Fig. 20. Initials « S » and « A » for Salón Azul 1998

All during my lengthy visit, I had something up my sleeve. Unbeknownst to the restorers, among the 1,476 postcards of El Salvador that I had collected was one of the National Palace interior!

When I dramatically brought out of a folder I had been carrying an enlarged copy of my postcard in Fig. 8., it produced on the part of one member of the crew a cry of astonishment! She said, « Stephen, we’ve been wondering what color pallette was used in the original paint job in the Blue Room, and could find no early images in our own archives. And here you show up with a color postcard just in the nick of time. » The power of a postcard lay in the utility to help inspire restoration efforts in an historical edifice, a national treasure. I’ll not forget the day: it was Thursday, April 30, 1998 at 10:30 am.

Fig. 21. Look of astonishment on face of restoration crew member1998

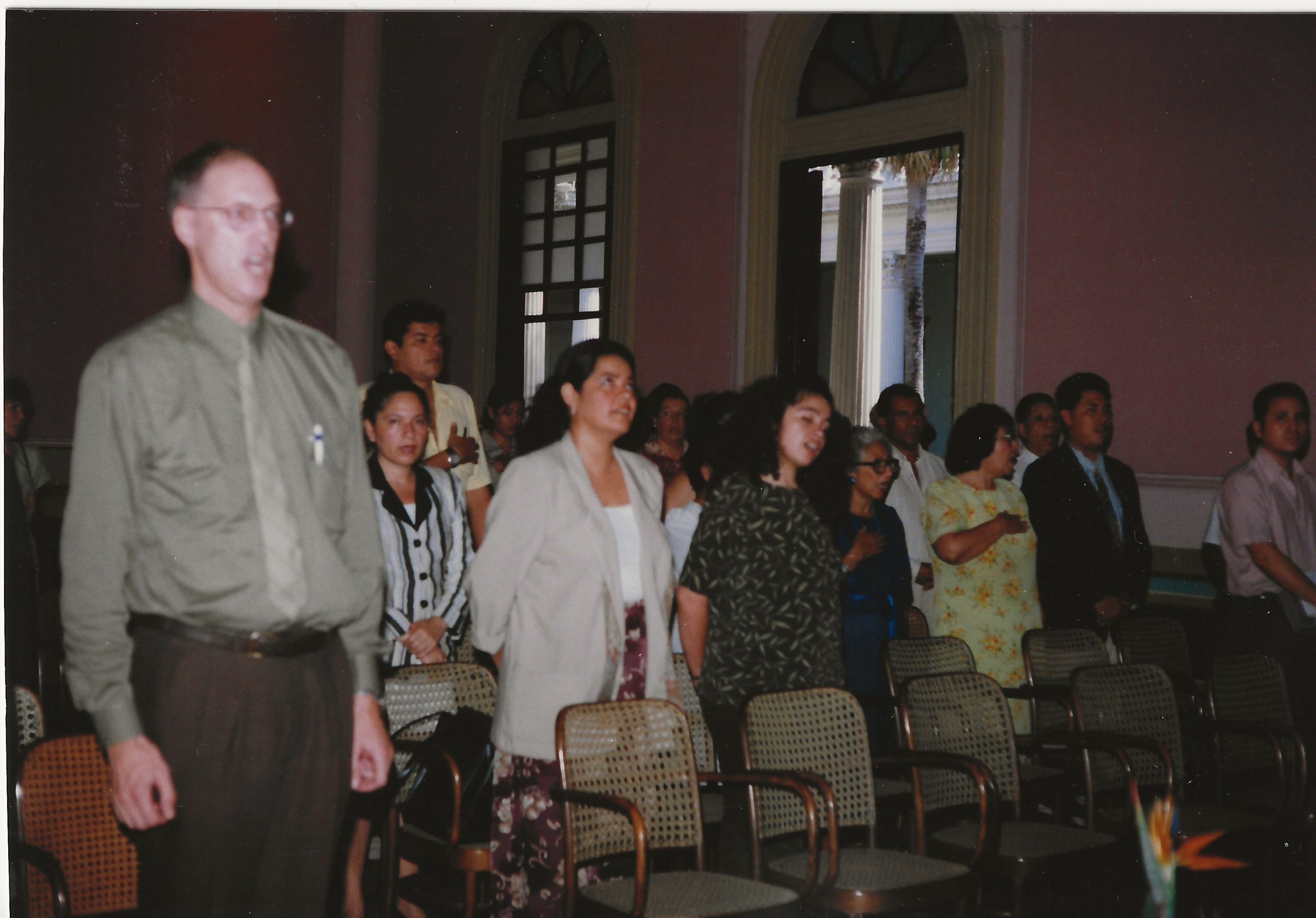

Two years later, I was invited to attend a meeting of the National Archives staff located in the National Palace. The formalities started off with the singing of the National Anthem. (Excuse the out-of-focus photo.)

Fig. 22. Singing the National Anthem in the National Palace with members of National Archives 2000

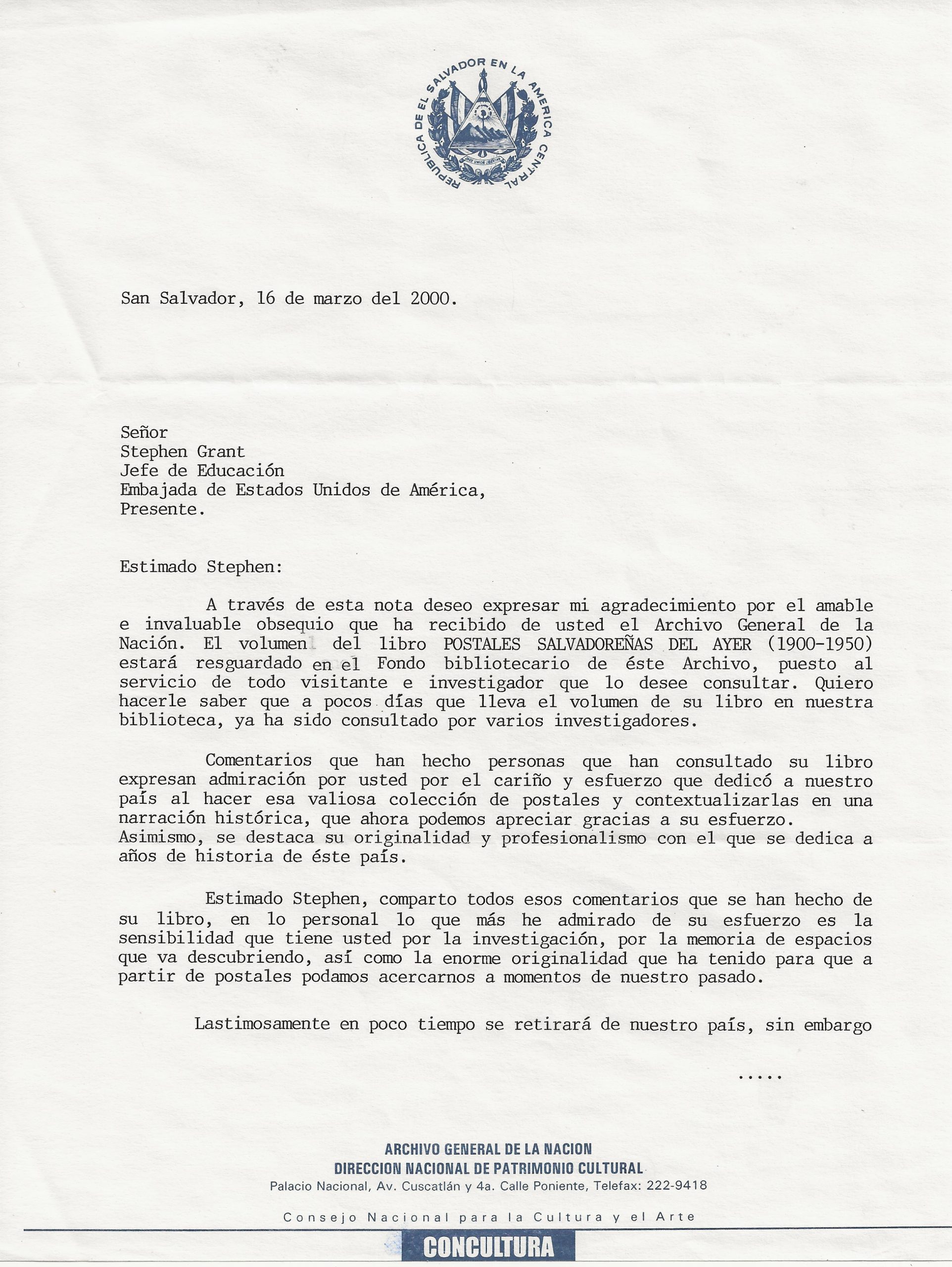

Before my departure for Washington, D.C. where I was reassigned for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), I returned to the National Palace to present a complimentary copy of Postales Salvadoreñas del Ayer/Early Salvadoran Postcards to the Director of the National Archives (Fig. 23.).

Fig. 23. Presentation of “Early Salvadoran Postcards” book to Director of National Archives 2000

Finally, Figs. 24. and 25. display the letter of acknowledgement I received from Eugenia López, Director of the National Archives.

Fig. 24. Letter of Gratitude from Director of National Archives 2000, p1

Fig. 25. Letter of Gratitude from Director of National Archives 2000, p2

COMMENTS:

10 Comments

Submit a Comment

CONNECT

I lived and worked in San Salvador for two years. This article brought back so many wonderful memories! I have always been fascinated by the stories that postcards tell us about our past. Although the story of Nando Gallegos’ death saddened me, he lives on in the story of the postcards he sent and that is comforting. Thanks so much for sharing the history of a beautiful building and the people connected to one of the postcards.

Hello Stephen,

I so enjoyed your article. Yes, the power of postcards.

The palace looks spectacular. I could just hear Encore singing

A concert in the palace.

Many thanks for the splendid research.

Thank you for the comment, Jeanne. We miss those singing trips.

Thank you , Stephen. This is very interesting and impressive!

I had the great pleasure of working with Steve for a few years during the late 90s. The true stories that evolved from Steve’s meticulous research were fascinating, indeed occasionally exposing well-kept secrets from the past. Steve was kind enough to gift me a copy of his book. It is now, and always will be a treasured addition to our home. The comments, conversations and laughs that it elicits from new Salvadoran friends are the stuff that long-term relationships are founded upon. After all, Salvadorans believe that if you ask a few questions about one’s relatives you will find that you are related. Hence, everyone knows someone in the book.

I have never been there but after your article I’m certainly visiting the place. It’s my country by the way, and just resentful it was vandalized and pillage by vandal and repainted the very next day by the government on Nayib Bukele.

Am sorry to hear of the incident, Reynaldo, but pleased to learn of the rapid repair.

Thanks! To you all, for the fresh description of the building in the center of my country ‘s capital. I did see it; but, never steped in.. I’d miss San Salvador..

In 1989 I was invited to consult with Salvadoran librarians who admirably were serving their patrons during the challenges of El Salvador’s civil war. The director of the National Archives provided a behind the scenes tour of the Palacio Nacional where the archives resided. I recall being amazed at the marble staircases and ornate ceilings; most especially I enjoyed the five towering Norfolk Pines in the Palacio’s courtyard. In 2001 after two massive earthquakes ruined the building of the private Biblioteca Gallardo, its collection of rare Salvadoran and Central American materials was transferred into the Palacio. I was invited to work with the collection for several weeks, so daily I entered through the majestic columns to be greeted by uniformed guards. The Palacio Nacional is a magnificent building filled with history, and I look forward to seeing its restoration.

Martha E. McPhail

Librarian Emeritus

San Diego State University

San Diego, California

During my tour as Cultural Affairs Officer at the U.S. Embassy in San Salvador, Steve Grant played a major role in introducing me to the culture and history of El Salvador. This included a visit to the National Palace and National Archives. Reading the comments and viewing the beautiful photos of the Palace, brings back good memories of my tour in El Salvador between 1998 and 2001. It was one of the highlights of my career in the Foreign Service.