The next three bas-reliefs along the Folger’s north wall are Macbeth, Julius Caesar, and King Lear. The images shown here are from the same two sets of postcards that were discussed in the previous post.

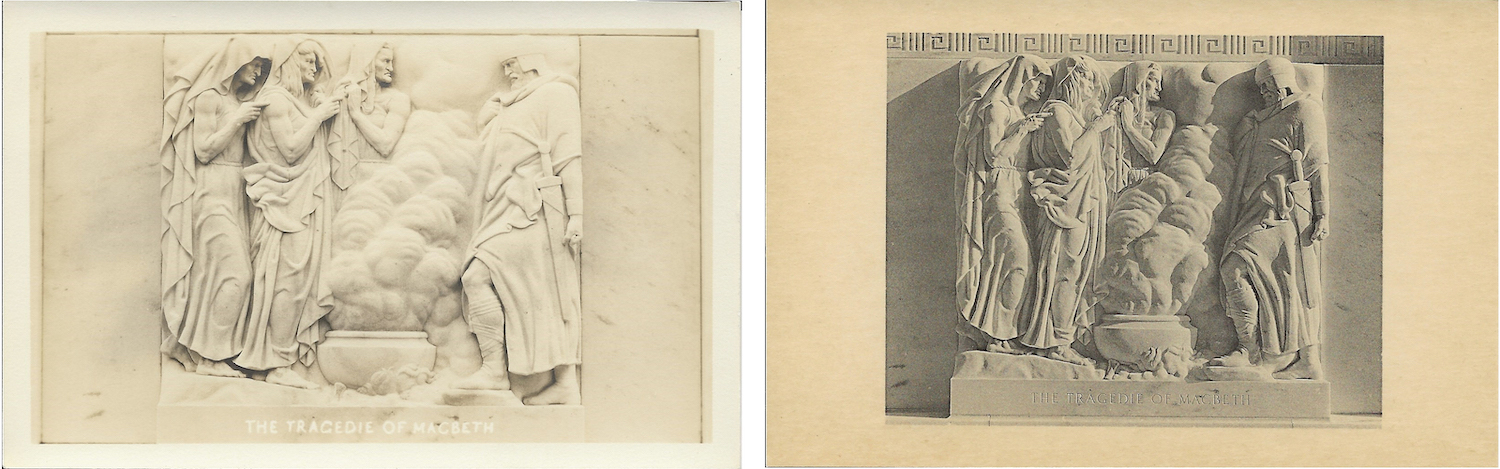

Fig. 1. Macbeth

Left: An AZO postcard

Right: A Meriden Gravure Co. postcard

(Author’s Collection, photo by Stephen Grant)

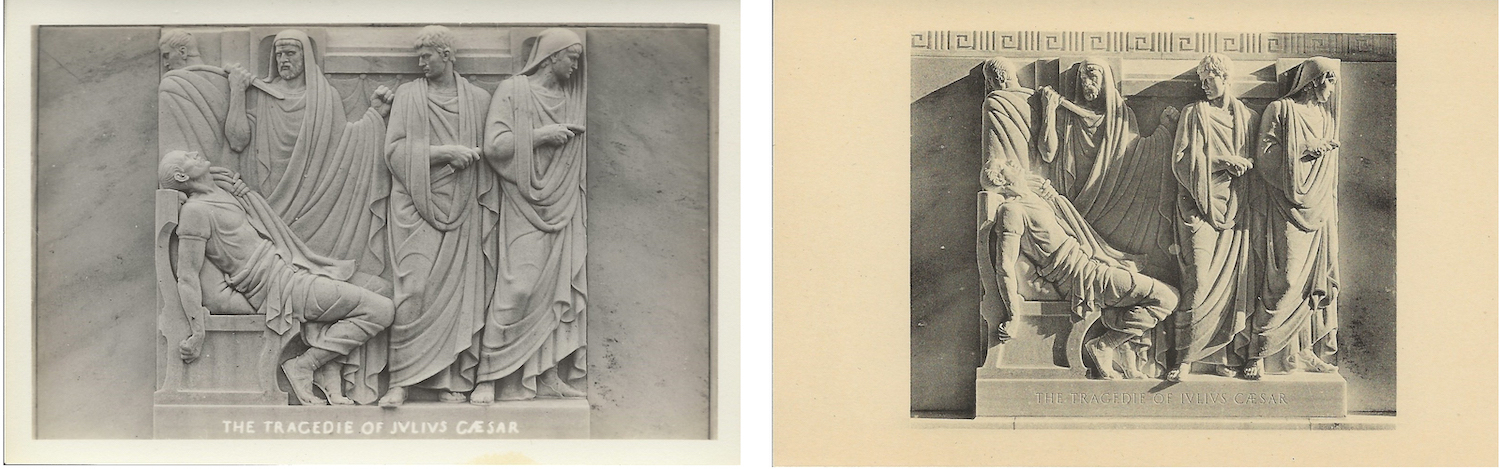

Fig. 2. Julius Caesar

Left: An AZO postcard

Right: A Meriden Gravure Co. postcard

Author’s Collection, photo by Stephen Grant

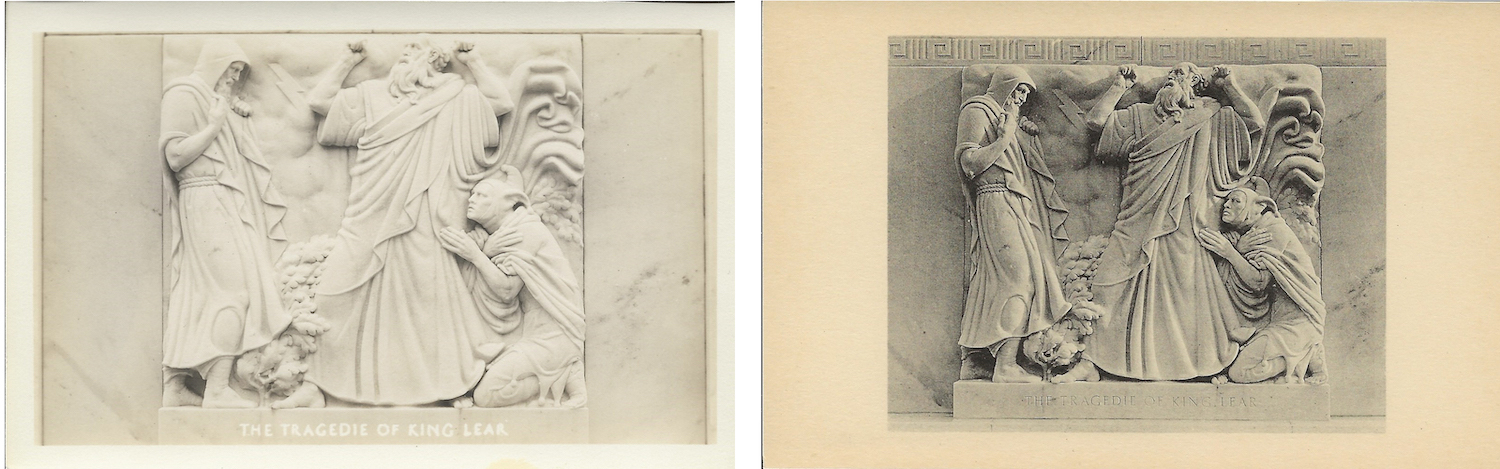

This post will focus on an anecdote related to the third of these bas-reliefs, the one of King Lear.

In the fall of 1929, principal architect Paul Cret and consulting architect Alexander Trowbridge identified four sculptors for the nine bas-reliefs project and asked them to prepare exhibits of their past work. Cret’s assistant John Harbeson accompanied the Folgers to view the exhibits. When the architects suggested that the Folgers visit each studio, Folger demurred: “I think you had better not bring us in until after you and Mr. Cret have decided upon the artist to be employed. After that it may be worth while to confer with the sculptor so as to make sure he clearly understands what we have in mind in the way of the designs he is to execute” (Folger Archives Box 57).

Trowbridge was struck by Mr. “Folger’s modesty, his deferring to the judgment of his architects on so important a matter as choice of a sculptor” (Folger Archives Box 57). After the architects confirmed that the British-born John Gregory was their first choice, the Folgers agreed to a studio visit. The Folgers liked what they saw. While there, Folger learned that Gregory, too, was a bibliophile who collected Charles Lamb and had studied Shakespeare’s influence on John Keats. This common passion created a bond between them and prompted Folger to make up his mind straightaway. “We need not visit any others,” he wrote to Trowbridge. “I am entirely satisfied to go ahead with Gregory; you fix up the contract, and bring it to me to see.” Estimating the work would require three years, Gregory agreed to start immediately.

In May 1930, the Folgers returned to the studio to assess Gregory’s progress. The sculptor showed his clients his model that was the farthest along, King Lear. As the couple departed, a relieved Gregory is reported to have heard Folger murmur, “I shall sleep well tonight.”

After the visit, Folger wrote Cret:

I will confess I have been much worried, fearing that he might not be equal to the task put upon him, but I was satisfied that you had, once more, made a successful choice in your assistant. I tried not to show too plainly that I was pleased with the work, and of course said little, or nothing, on the subject to Mr. Gregory, preferring, as I do in all cases, that what I say should reach him with your approval and through you as a medium, rather than direct; so I am now writing you, instead of communicating either by word of mouth or by letter, with him, and will leave it to your judgment what you will pass on to him as coming from me (Folger Archives Box 57).

While Folger generally liked what he saw, he nevertheless noticed some aspects that he was not quite satisfied with. In a letter to the architects—not the sculptor—Folger outlined his desires. He wanted to see a Lear a bit older and slightly more distraught. Lear’s upraised arms should be a little more muscular, the Fool a little younger. Cret conveyed these suggestions to Gregory, who made the changes. Alas, Folger never saw the modified version. By mid-June of 1930, Henry Folger had died.

Fig. 3. King Lear

Left: An AZO postcard

Right: A Meriden Gravure Co. postcard

(Author’s Collection, photo by Stephen Grant)

(This post was originally published on the Folger Shakespeare Library’s research blog The Collation on October 20, 2020.)

COMMENTS:

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

CONNECT

Hi Stephen…loved all your photos, and glad you put to good use all those post cards I gave you!