Where were you for Y2K, at the change of millennia from 1999 to 2000?

I was in El Salvador as deputy leader of the economic growth strategic team at USAID/San Salvador in El Salvador, Central America. This team’s portfolio included 15 activities in education, training, agriculture, microenterprise, infrastructure, land titling, and economic policy. A neighbor, Mary, was team leader and the American Embassy’s “duty officer” that week. As the last hours of 1999 ebbed, no one knew for sure what worldwide calamity might befall the planet. Many computer programs allowed only two digits (e.g., 99 instead of 1999). People feared that computers would be unable to operate when the date descended from “99” to “00.” Would computers crash? The Embassy communications officer delivered to Mary’s residence an incredible set of telephones and coded numbers so she could connect virtually with anyone anywhere in case of an emergency. At midnight no disaster was reported and immense panic turned to utter relief.

Alongside my work with the Salvadoran Ministry of Education and UNICEF in the late 1990s, I conducted research to produce a bilingual book––printed in San Salvador in 1999––on vintage Salvadoran postcards (Fig. 1).

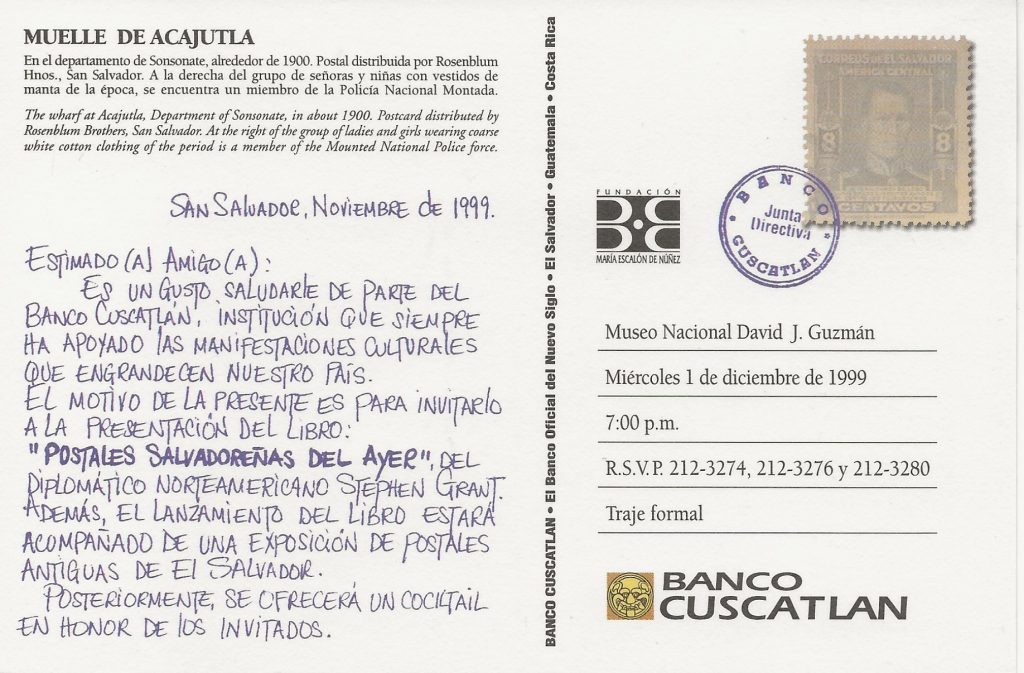

The book was officially launched on Dec. 1, 1999 in the David J. Guzmán National Museum in San Salvador (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

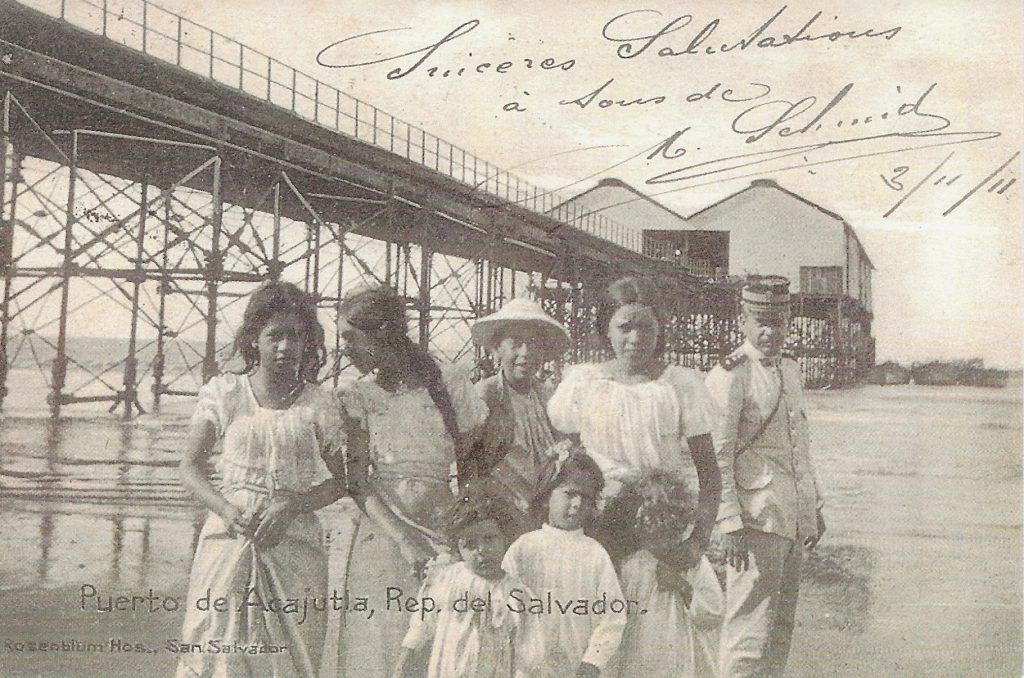

Fig. 2. Postcard of Wharf in Acajutla, El Salvador sent on Mar. 11, 1911

Fig. 3. Invitation to Book Launch in David J. Guzmán National Museum

Speakers included Pedro Antonio Escalante Arce, Secretary of Salvadoran Academy of History; Gustavo Herodier, President of CONCULTURA; Anne Patterson, American Ambassador; Mauricio Samayoa, President of Banco Cuscatlan, and the author.

Since the 1980s, I had been a “deltiologist,” that is someone who collects, studies, and analyzes picture postcards. No book on Salvadoran postcards had ever been written before. I had the honor to present the volume to the vice-president of El Salvador, Carlos Quintanilla Schmidt (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Presentation to Vice-President of the Republic of El Salvador

A letter of thanks (Fig. 5, Fig.6) points to his affirmation that studying their roots will permit Salvadorans to create their own identity as a nation.

Fig. 5. Vice-President’s Expression of Gratitude, page one

Fig. 6. Vice-President’s Expression of Gratitude, page two

In presenting a copy of Postales Salvadoreñas del Ayer to Eugenia López (Fig. 7), director of the Salvadoran National Archives, I knew the volume would be used.

Fig. 7. Presentation to Director of National Archives of El Salvador

In her letter of appreciation, the director cited the enormous originality in selecting picture postcards as a basis for an historical study adding to the value of providing an accompanying historical narration (Fig. 8, Fig. 9).

Fig. 8. Expression of Gratitude from Director of National Archives, page one

Fig. 9. Expression of Gratitude from Director of National Archives, page two

Early Salvadoran Postcards was for sale in several San Salvador bookstores, in two Antigua, Guatemala bookshops, from the publisher María Escalón de Núñez Foundation in San Salvador, from the sponsor Banco Cuscatlán, and on Amazon. As befitting a coffee-table book that weighs 5 lbs., the book joined other large-size, profusely illustrated tomes in one San Salvador gift shop display rack (Fig. 10), where my neighbors consisted of such illustrious artists as Renoir, Cezanne, Gauguin, and Antoine de St. Exupéry.

Fig. 10. Famous Neighbors in San Salvador Book Shop

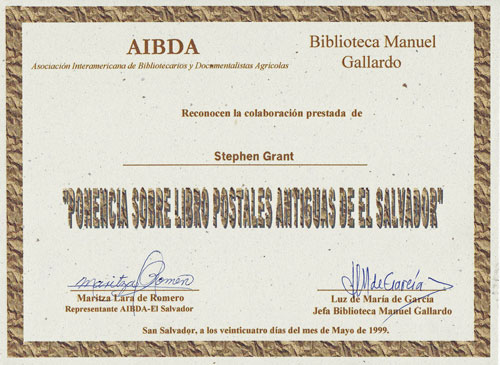

Maritza Lara de Romero representing the Interamerican Association of Librarians of El Salvador and Luz de Maria de Garcia, head of the Manuel Gallardo Library in Santa Tecla, El Salvador, jointly bestowed an award (Fig. 11) recognizing my collaboration.

Fig. 11. Award from Interamerican Library Association, Gallardo Library

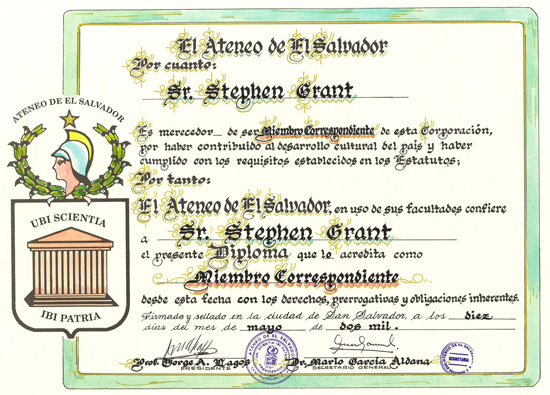

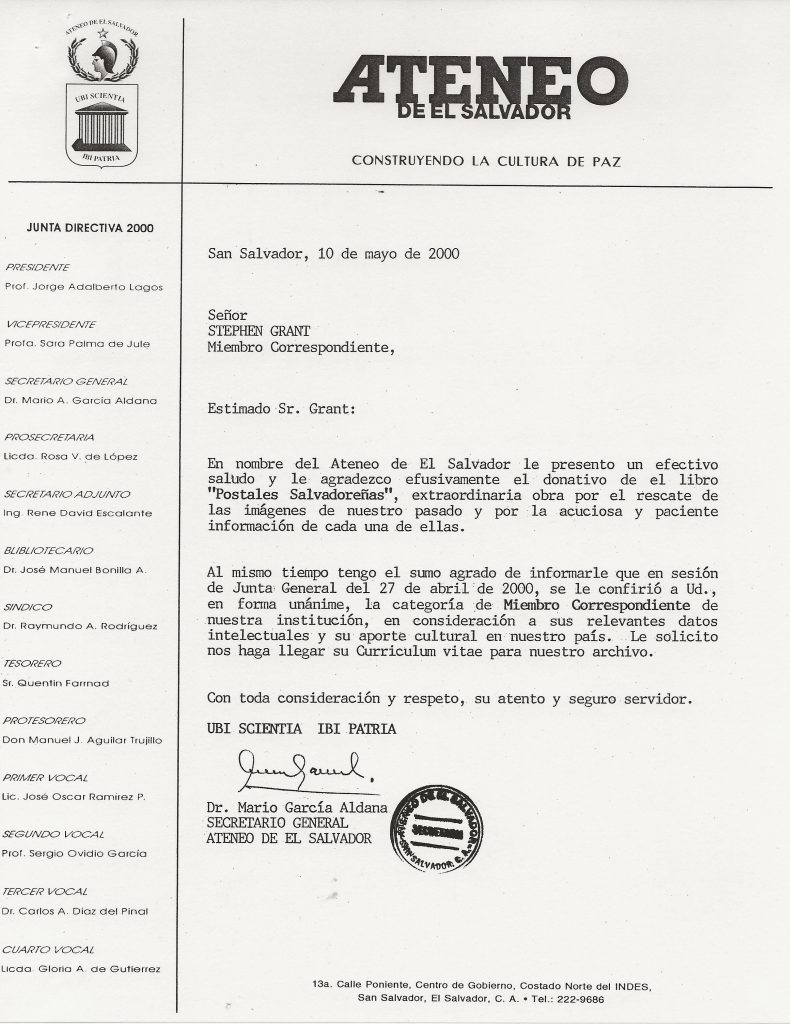

I conducted research in the rich Gallardo Library and attended meetings of the Association. The Ateneo (Athenaeum) de Salvador conferred a diploma of guest membership (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Award from Ateneo of El Salvador

Dr. Mario Garcia Aldana, secretary general of the organization, in a letter (Fig. 13) expressed gratitude for my having saved historic images of the country’s past and patiently recorded information about each one.

Fig. 13. Expression of Gratitude from Ateneo of El Salvador

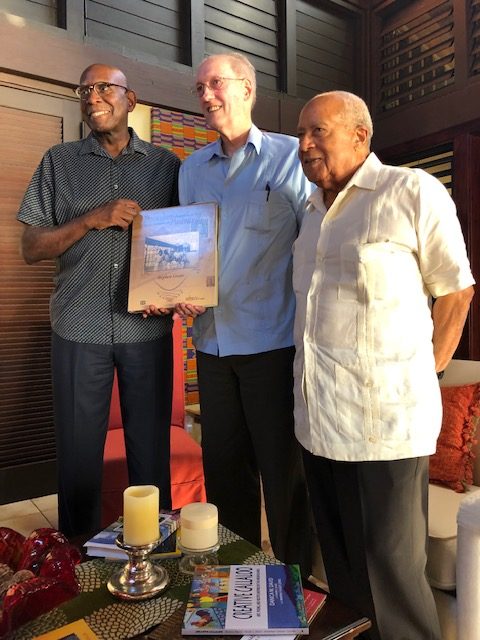

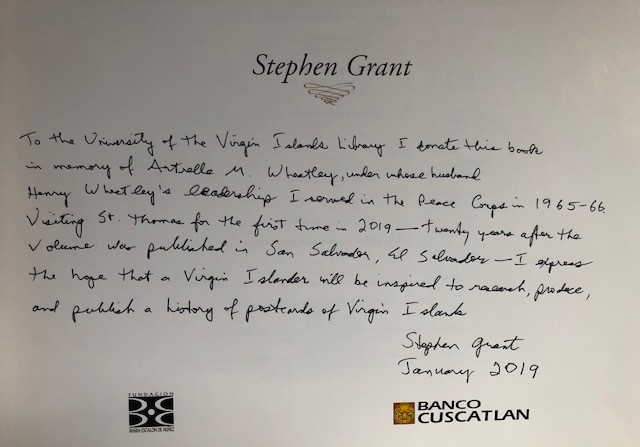

On my travels to the Caribbean and South America, I often meet with librarians, archivists, and educators. In St. Thomas, I met with Dr. David Hall, president of the University of the Virgin Islands (UVI). In presenting him with the Salvadoran postcard book for the University library, a special participant in the ceremony was my Peace Corps director, Henry Wheatley (on the right), going back to 1966 in Cote d’Ivoire, West Africa. He is a Virgin Islander, whose late wife used to work for the university (Fig. 14, Fig. 15, Fig. 16, Fig. 17). I have agreed to act as advisor to the UVI if they identify a local prospect to begin research on a similar postcard book project.

Fig. 14. Presentation to President of University of Virgin Islands

Fig. 15. Author’s Inscription in Memory of Artrelle M. Wheatley

Fig. 16. Welcome Sign to University of Virgin Islands in St. Thomas

Fig. 17. Entrance to Ralph M. Paiewonsky Library at UVI

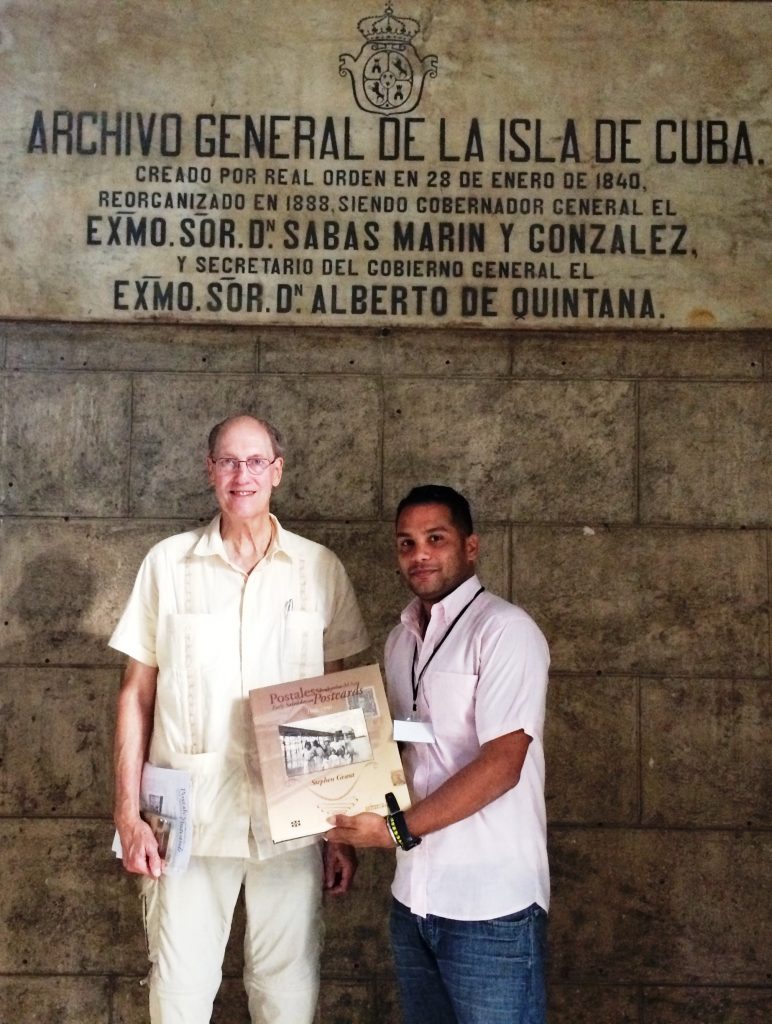

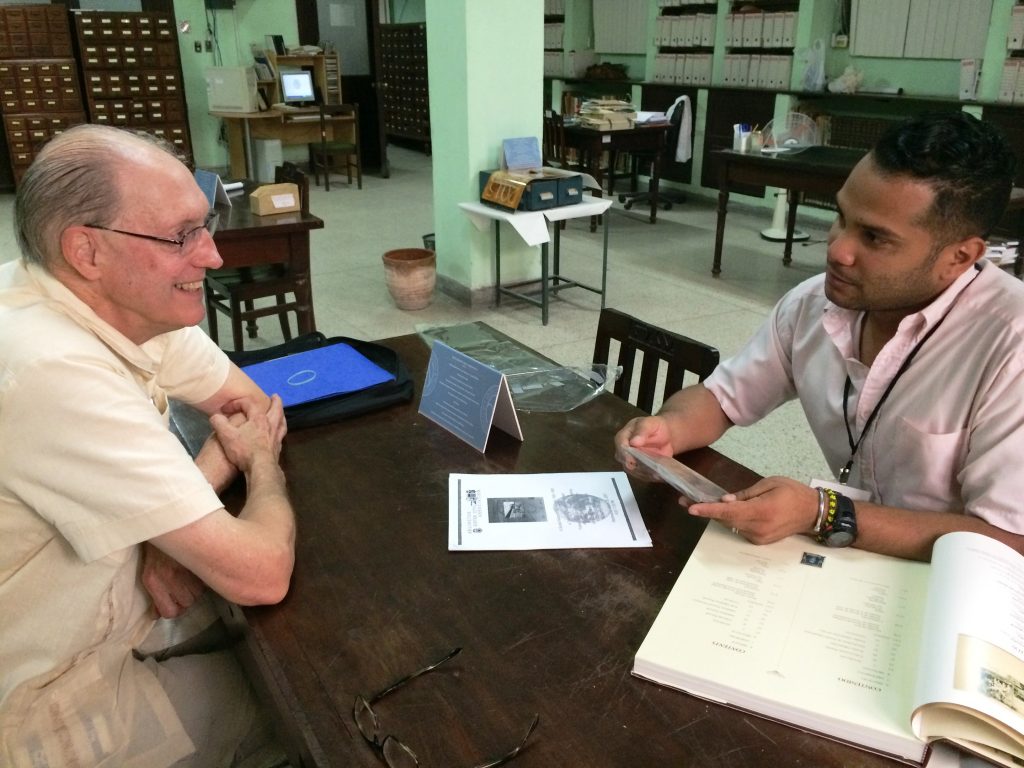

Director-general of national archives in Havana, Cuba, Martha Ferriol, had me meet with her assistant Lopez for a presentation (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18. Presentation of Salvadoran Postcard Book to National Archives of Cuba

I also gave the national archives in Havana several old picture postcards of Cuba for its collection (Fig. 19).

Fi. 19. Presentation of Old Cuban Postcards to National Archives of Cuba

Lopez asked about the value of the cards and where I had acquired them. The archives recorded the gift on its website. Finally, I made a similar presentation to Alexandra Werneck, supervisor in the biblioteca nacional in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Fig. 20).

Fig. 20. Presentation of Book to Biblioteca Nacional in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

In the year Y2K, I returned from El Salvador to Washington, DC, to devote my last three years as a Foreign Service officer coordinating support for USAID programs in 14 West African countries. The residential community I reverted to––Lyon Village in Arlington, Virginia––contained numerous Salvadoran families and business operations including restaurants. Leading up to National Library Week in 2007, I gave a talk in the Arlington Central Library on Early Salvadoran Postcards (Fig. 21). Arlington maintains a sister-city relationship with St. Miguel in El Salvador.

Fig. 21. Author’s Book Talk and Signing at Arlington, Virginia Library

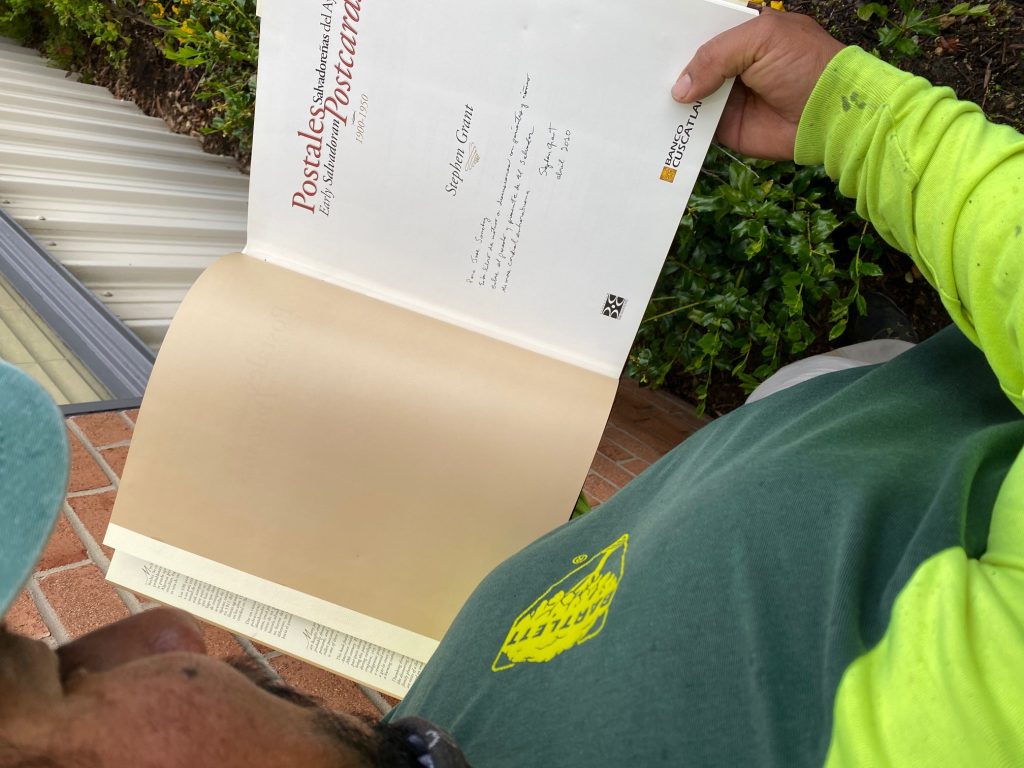

When I moved to Arlington, Va. in 1975, the predominant immigrant group appeared to be Vietnamese, as the Vietnam Was ended. In 2000, it appeared to be Salvadoran, after their Civil War. As an example, during my years abroad in the Foreign Service I rented my house early on to Vietnamese and toward the end to Salvadorans. Now as a retiree I hire mainly Salvadorans for lawn and tree care. These excellent workers are learning a trade, providing needed services, and,

in this case, adding to their home library a book that they can use to explain to the children about the country they come from, and can show to their parents who grew up in a very different El Salvador from that of today (Fig. 22, Fig. 23, Fig. 24).

Fig. 22. Salvadoran Arborists Receive Postcard Book in Northern Virginia

Fig. 23. First Glimpse into book on Salvadoran History 1900–1950

Fig. 24. Bilingual Book is Personally Inscribed to Arborists

COMMENTS:

CONNECT

0 Comments