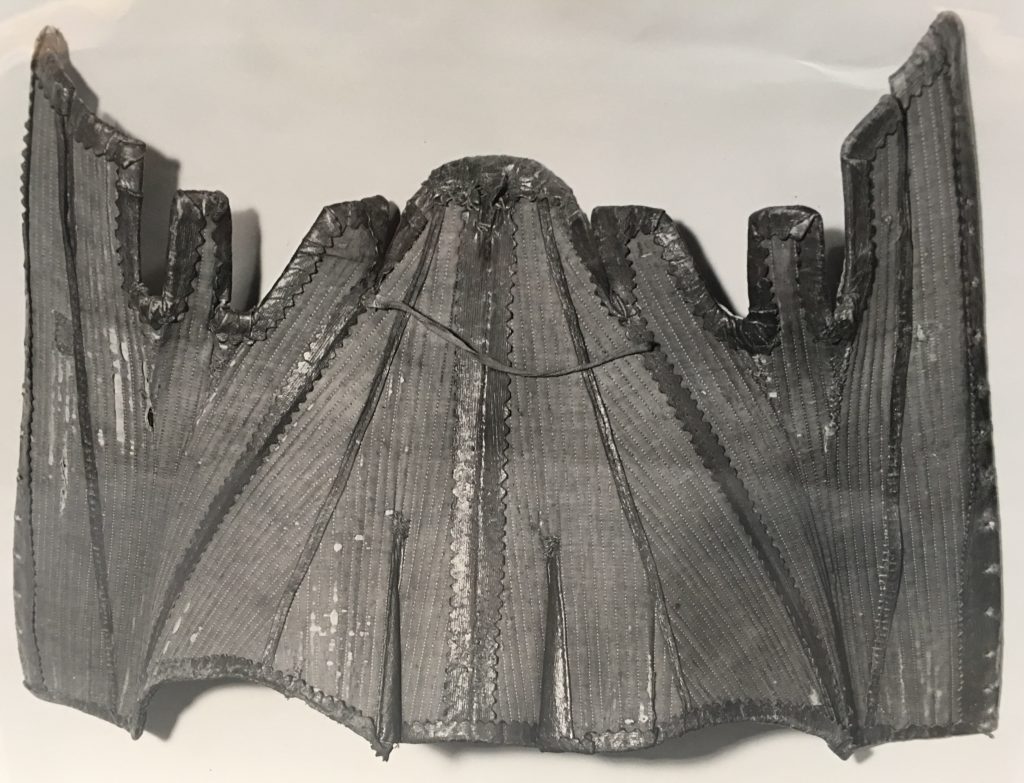

In 1926 Henry Folger purchased from Montmartre Gallery in London this object

advertised as “Queen Elizabeth’s Stays”

In October 1931, armored trucks left Brooklyn––where Shakespeare collectors Henry and Emily Folger had lived––for a night ride to Washington DC. Security guards packed Colt .45 pistols, riot guns, and tear-gas bombs. When Folger Shakespeare Library staff unpacked the 2100 cases constituting the Folger collection, they were in for a few surprises. Inside case no. 1911 they discovered catalog Curiosa C from Montmartre Gallery, 39 Wardour Street, London W1 and item no. 551, “Queen Elizabeth’s Corsets.”

In November 2016, I filled out a call slip in the Library and the item was brought to my table in the reading room. I opened a black box embossed in gold, “Queen Elizabeth’s Stays.” The plural signified a pair of stays, right and left side. The garment with faded Moroccan red-leather trimming was folded several times. Tucked over it were framed pedigree and receipt.

The article had been in the family of an aged woman, Mary Ann Pilgrim, for 300 years. Furthermore the Queen was said to have given the item to a Mrs. Shackles who in turn gave it to one of her maids named Pilgrim. The receipt signed by N. W. Davis indicates that Folger purchased the lot on November 11, 1926 for £10. The Gallery had priced it at £11. Folger customarily informed his dealers that he was taking 10% discount because he paid in ready cash!

Henry Folger was not the only New Yorker to covet the corset. George A. Plimpton attended Amherst College at the same time as Folger, and they both collected Shakespeare. Running into Folger on the street one day, Plimpton boasted, “I got ahead of you this time, Henry. I just ordered Elizabeth’s corset by special delivery.” Folger retorted, “You should have cabled. I did.”

Word slipped out about the royal undergarment under first Folger director William Adams Slade (1932–34). Tourists demanded to see the pair of stays. Slade tried to redirect their attention to another regal possession. “But we have Queen Elizabeth’s Bible, a very precious item, plush red with brass knobs.” “We want the corset,” chimed the chorus.

Second Folger director Joseph Quincy Adams (1934–1946) added the corset to his first exhibit in the Great Hall. The news reached the National Geographic magazine staff, who included the story in “Wonders of the New Washington,” vol. LXVII, no. 4, April 1935. A lady in the Folger library is pictured near the stone fireplace in the reading room unfolding the garment on a small round table.

Still looking for a story fifteen years later, National Geographic published “Folger: Biggest Little Library in the World,” vol. C, no. 3, September 1951. Model Betty Jo Hanna was photographed squeezing into the corset, aided by Folger cataloguer Lilly Stone (Lievsay).

As he recounts in his memoir, Folger reference librarian Giles Dawson began to doubt the authenticity of the corset. He sent a color photo of it to Victoria and Albert Museum in London for an appraisal. Assistant keeper in the Textiles Department Donald King––who would become the world’s expert on British textiles––sent back this assessment. “The corset illustrated appears to me to belong to the first half of the eighteenth century; no such corsets are known from the Elizabethan period.”

The New York Times released an article, “Legend of Corset of Queen Fizzles” on February 29, 1956. Third Folger director Louis B. Wright (1948–1968) was forced to admit, “the corset’s a fake.” It was quietly removed from the display case.

(This post originally appeared on Blogging Shakespeare by Shakespeare Birthplace Trust on December 23, 2016.)

COMMENTS:

CONNECT

0 Comments