On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of Senegalese President Léopold Senghor’s death, on December 7, 2021 Yves Thréard wrote an article in Le Figaro entitled “Il y a vingt ans, disparaissait Léopold Sédar Senghor, un intellectuel aux antipodes de la ‘cancel culture.’” The author points out that President Senghor showed an equal appetite for politics as for literature. Senghor was admired for his powers of reflection and the dimension of his visions. He was the first African head of state to step down from power on his own. After serving for 20 years as the first president of Senegal after decades of colonial rule by France, Senghor groomed his successor who also served for 20 years, producing a rare example of stability. The father of his country was a pillar of democracy. He was a Roman Catholic in a country of Islamic majority. For many years he traveled to the world’s political hot spots as a member of the “Council of Sages” to try to help stymied leaders solve complex political issues. Today it is thought his presence would have been useful to share his perspectives on the practice of “counter-culture” and the phenomenon of “wokism.” Senghor was the first black man to be elected to the French Academy (Académie Française); he was an assiduous participant in the Wednesday sessions to advance the development of the Academy’s dictionary. “Le wokisme” might well have been on the agenda for a robust debate.

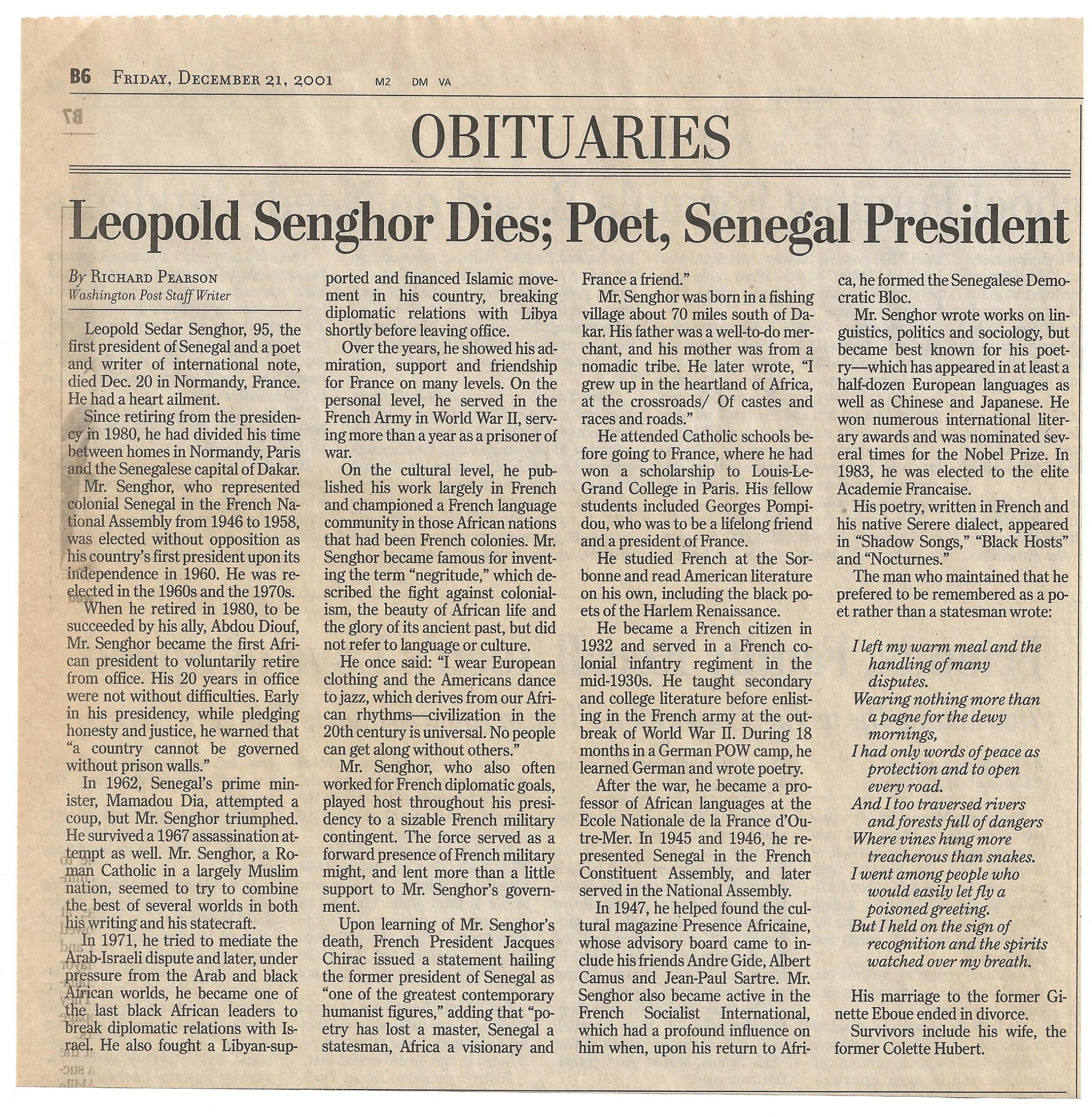

This post is a brief addendum to a more substantive blog post on President Senghor released on July 16, 2020 and entitled, “Interviewing President Senghor.” Léopold Sédar Senghor was elected in 1960 as the first president of the Republic of Senegal in West Africa after independence from France, serving in that capacity for 20 years. Known as the “poet-president,” he championed the cultural richness and diversity of the African continent. When Senghor died at the age of 95 in 2001, French President Jacques Chirac called him “one of the greatest contemporary humanist figures. Poetry has lost a master, Senegal a statesman, Africa a visionary, and France a friend.” I was lucky to be invited to Senghor’s home in Dakar for an interview, and met with him subsequently in Cairo.” During the 20 years that I spent in Africa as a Peace Corps Volunteer, a UNESCO consultant, and a Foreign Service officer for USAID, I viewed President Senghor as a towering figure, who was astoundingly generous with his time when I sought to approach him.”

Here are the six questions I asked President Senghor (in French):

One. It is said, Mr. President, that you do not miss being in power; you prepare lectures, write, and travel extensively. One can imagine that relieved of many constraints, you are occupied with projects that you had placed on the back burner during your presidency. Is that an accurate portrait?

Two. You have recently been elected to the French Academy, a high honor by which France has recognized your personal merit. Through it, you as well as the African continent and black Francophone literature are honored. What contribution do you hope to make to this institution?

Three. You have said that the greatest civilizations are “crossbred.” Can you provide concrete examples of what you mean by this term?

Four. Adopting biological and cultural crossbreeding as an intellectual theory is one thing, but are there also practical political applications? For instance, do you believe that understanding and appreciating other civilizations can increase the chances for conflict resolution among nations?

Five. Besides your writings, are there other channels through which you can promote cultural crossbreeding as a means of approaching “universal civilization?”

Six. What influence would you like to exert on the younger generation?

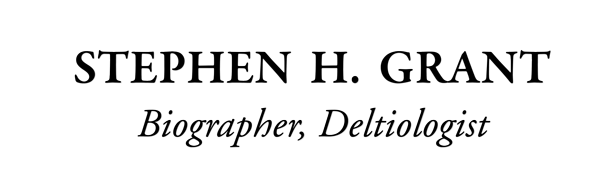

President Senghor is the perfect subject to interview. You push a button and he expounds at length in beautifully crafted sentences. Photo by Papa Diaw

Behind the President in this 1983 interview held in his Dakar, Senegal home is a photo of son Philippe Senghor who died in a traffic accident at age 23. Photo by Papa Diaw

This was not the only presidential interview of my career. In 1973 I interviewed General Sangoulé Lamizana, President of Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) in the spartan camp militaire where he preferred to live rather than in the lavish presidential palace in Ouagadougou. Both interviews were published in Africa Report. Photo by Papa Diaw

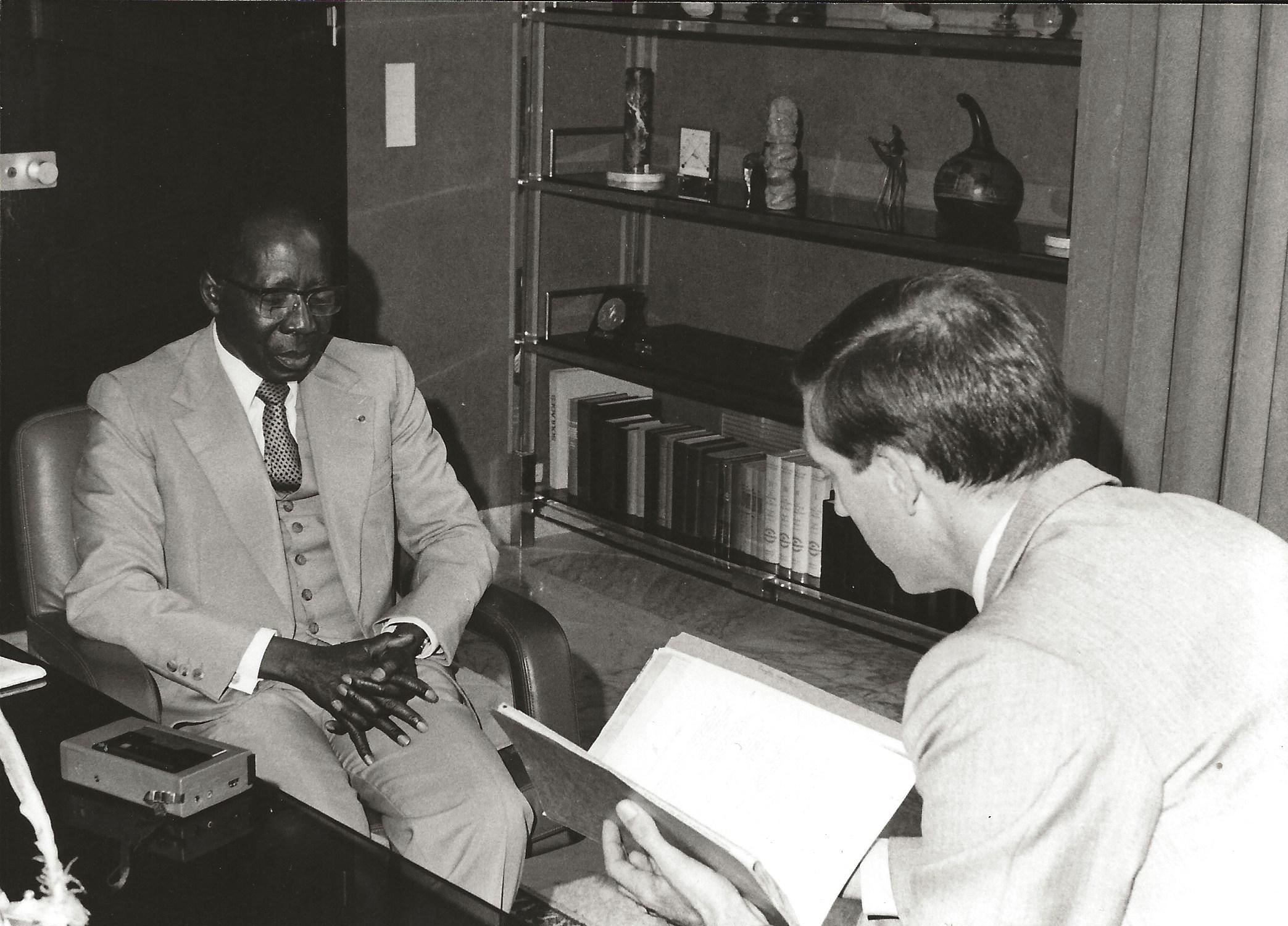

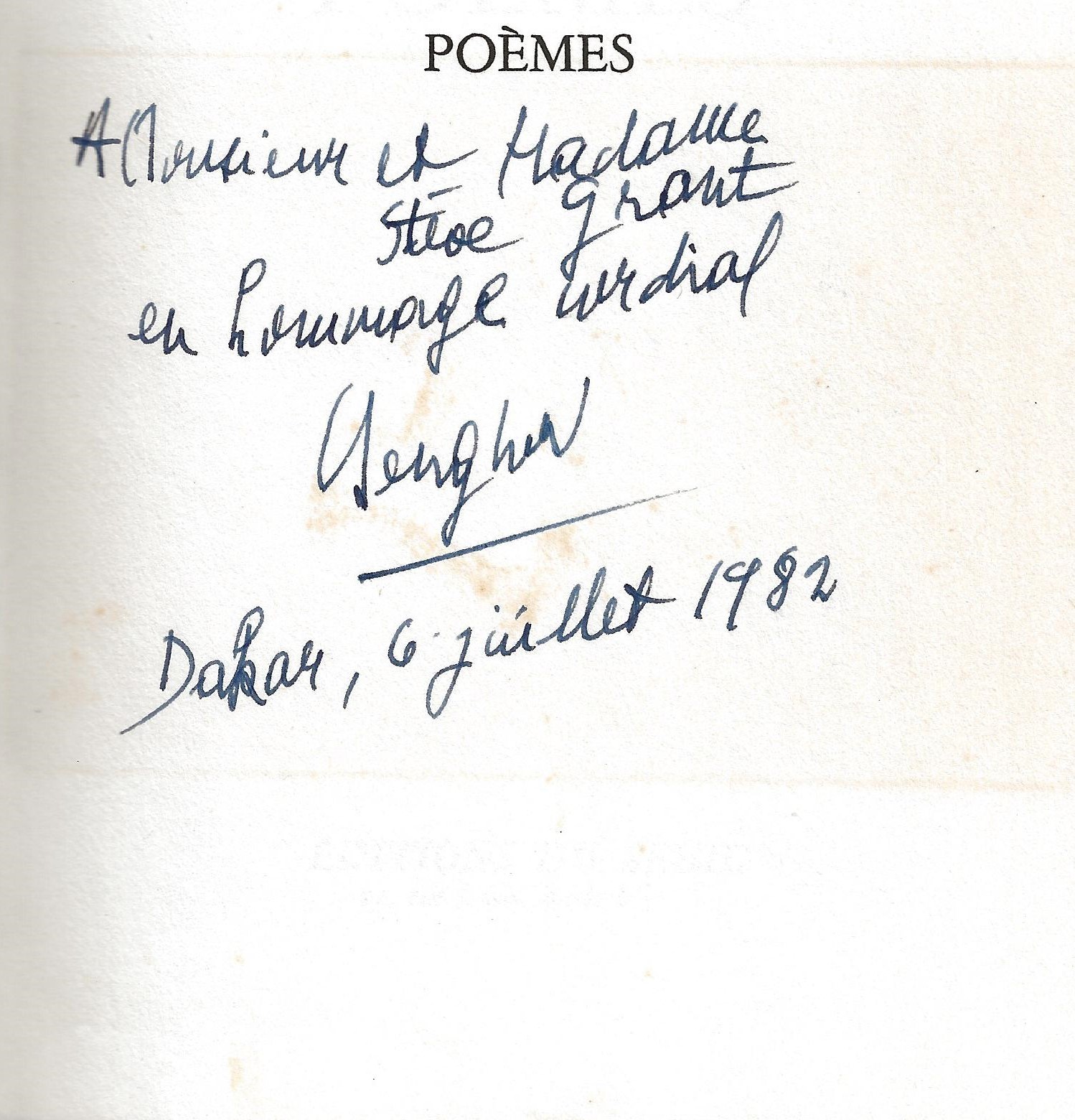

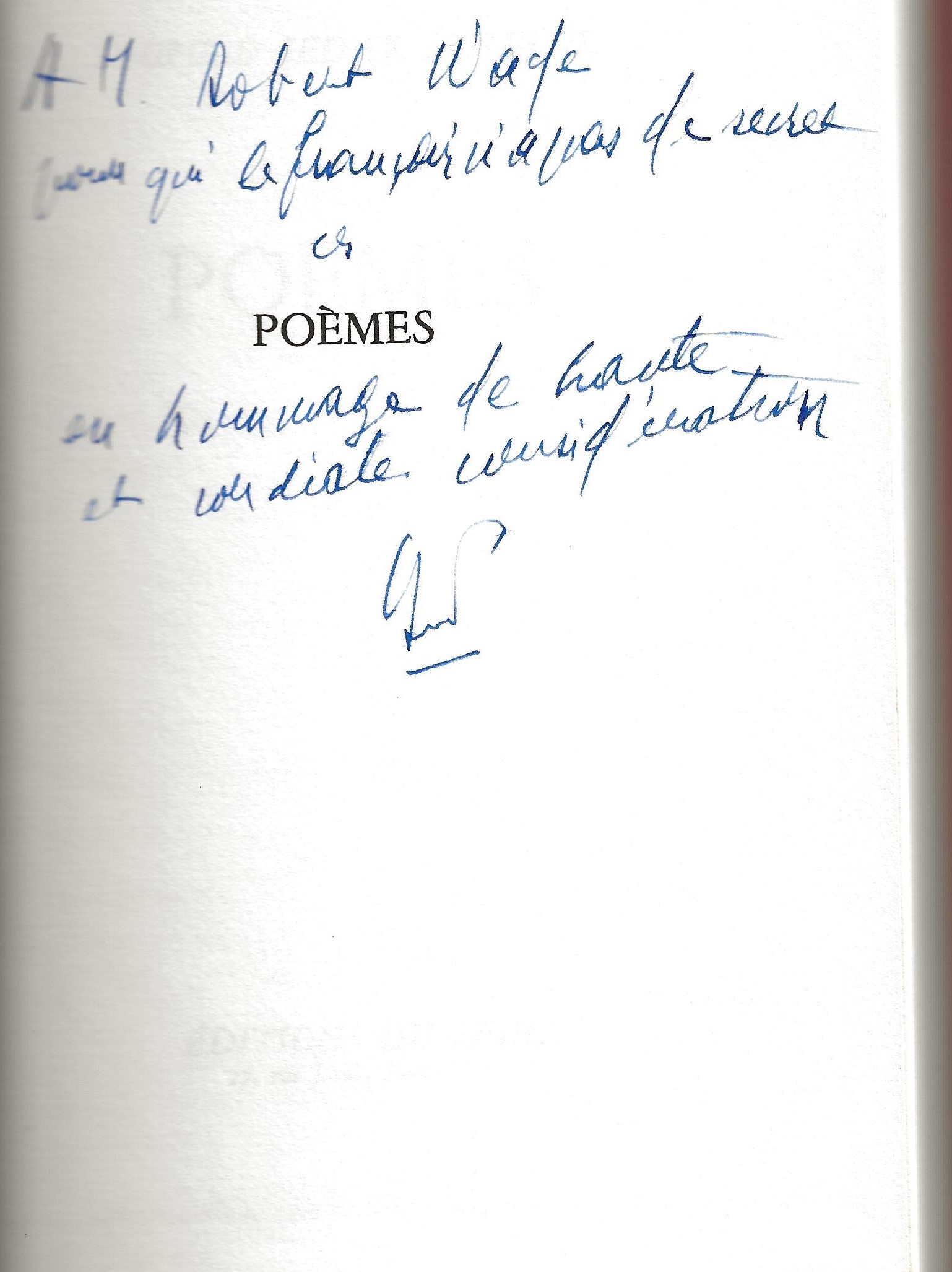

Many famous people cannot be bothered by inscribing their books, or they dash off an illegible signature. President Senghor takes out his own fountain pen with blue ink and carefully pens a thoughtful message. Photo by Papa Diaw

Madame Annick Grant taught French and African Literature in Egypt, Ivory Coast, Guinea, Indonesia, and El Salvador. She caught up with President Senghor in Cairo, where she questioned him about Chaka, a dramatic poem from the volume, “Ethiopiques” (1956). Photo by Stephen Grant

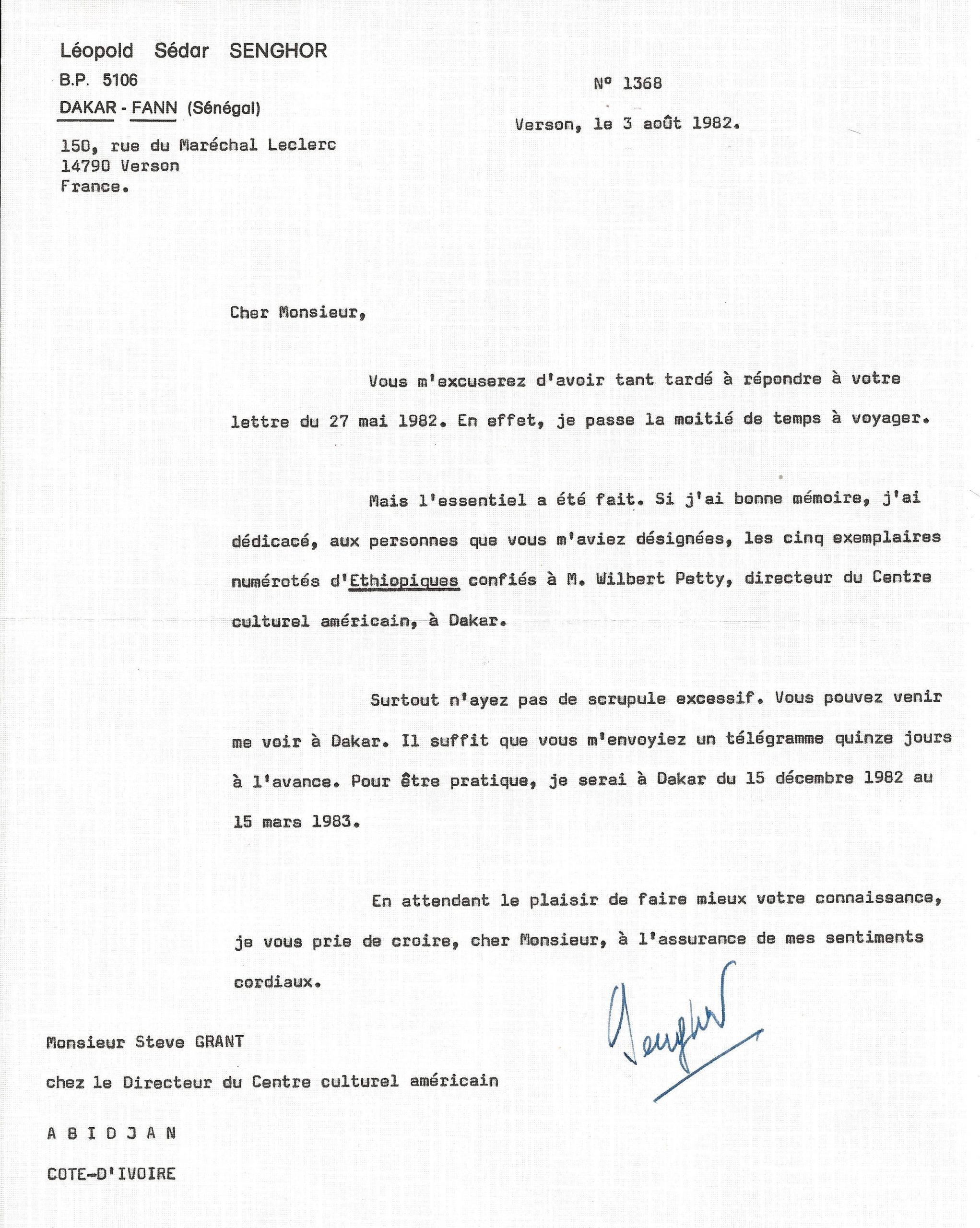

I am most fortunate to have conducted a modest epistolary exchange with President Senghor. This August, 1982 letter was numbered (1368) and sent from Verson in Normandy where his wife Colette hails from. In it, Senghor reveals that even at age 77 he carries out a demanding travel schedule; I did not expect him to apologize for a tardy reply. In addition, I was flabbergasted when “the African sage” offered me the formula to obtain an audience: cable him between Dec. 15 and Mar. 15. The scheme worked.

1964 was a big year for Léopold Sédar Senghor on the literary side. A major French publishing firm, Editions du Seuil, in Paris, published in stunning red-cloth binding a 254-page volume of Senghor’s poems. I am somewhat of a book collector, and possess three copies which I have displayed on three pillow covers (made by El Hadj Tall) that I purchased in Dakar: a first edition numbered 2745; a fourth edition numbered 8674, and a seventh edition numbered 18034.

My copy of the seventh edition is inscribed to M. Robert Wade. At some point he or his heirs gave it up, and I purchased the copy at a Book Fair in the U. S. State Department where I worked as a volunteer and manned the “Authors’ Table.” Have you ever wondered about the nicknames famous people acquire? You can see in image 10 that Senghor signs the book, “Léo.” Then, keep in mind what Georges Pompidou called L. S. Senghor while they were classmates in a grande école in Paris and before they both were elected presidents of their respective nations, “Ngor.” Here are two nicknames: Léo and Ngor. Who knew?

COMMENTS:

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

CONNECT

Steve,

I enjoyed all of these comments and photos. I, too, was a great admirer of Senghor when I discovered him in 1969, on arrival in Senegal, our first post with State Dept. Dane was a junior officer doing consular work. I started an English class for Senegalese women, who at that time, would not attend class with the men.

As a student of African Lit and a learner of French, I cherish my volume of Senghor’s poems.