“I’m a longtime fan of both the literary treasures within the Folger, and its stunning Greco Deco exterior architecture. A friend alerted me to Stephen Grant’s scholarly yet utterly charming tale of Henry Folger and this history of post(al) cards, as well as the declining art of collegiate oratory. What a treat.”

Annie Groer

My first descent into the underground vault took place in 2007 during a short-term Folger fellowship. Since a Summer Retrospective is the order of the day with The Collation, I should like to acknowledge the Feb. 16, 2012 post honoring fellowship administrator, Carol Brobeck. With a tape measure stuffed into a side pocket, I trailed Betsy Walsh, head of reader services, as she led me to yards of shelving supporting dozens of gray archival boxes 10 x 13 x 4” laid out horizontally that formed the Folger Collection she called “Folger Coll.” The Sept. 26, 2017 Collation post is a tribute to Betsy. “What had I signed up for?” I wanted to learn. You see, while the other 39 fellows that year came to consult the collecTION, I would do that but concentrate on the collecTORS. We tallied 25 linear feet. I found the figure staggering, but good to know. My fellowship evaluation sheet submitted to Carol on Bastille Day 2008 was entitled, “Initial research for a biography of Henry and Emily Folger.”

Johns Hopkins Press released Collecting Shakespeare: The Story of Henry and Emily Folger on the Ides of March 2014. The first biography of the founders appeared four score and two years after the Folger Shakespeare Library was dedicated on Shakespeare’s 368th birthday in 1932.

Prior to becoming a biographer I was a deltiologist. Collins Dictionary defines deltiology as the collection and study of picture postcards. Before I authored two biographies I wrote three books on vintage postcards of Guinea in West Africa, Indonesia in South Asia, and El Salvador in Central America, published in those countries.

My posts for The Collation will center on postcards in the Folger Archives boxes. For this initial post, we will scrutinize together the earliest-dated postcard.

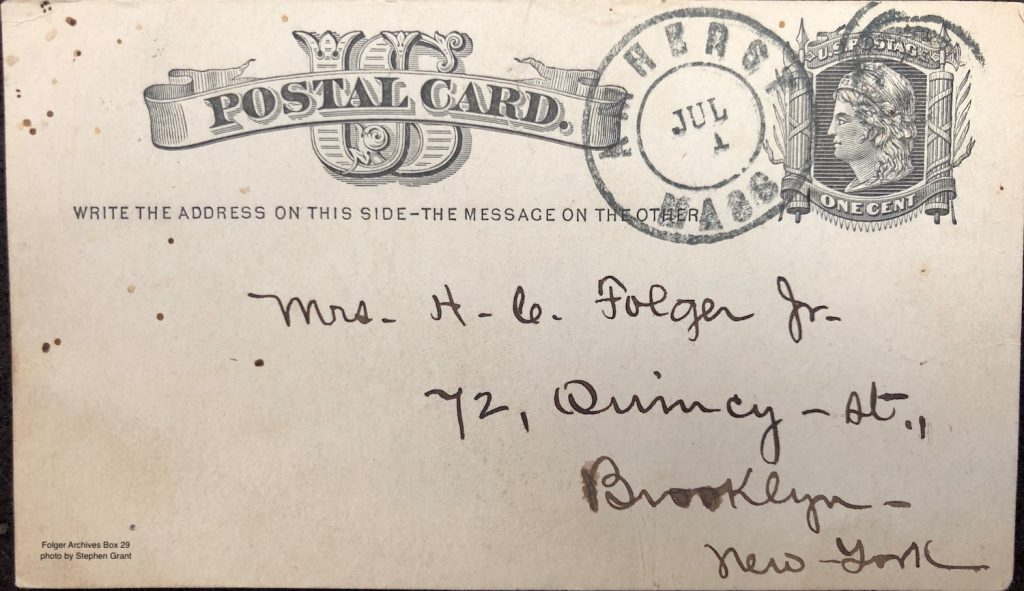

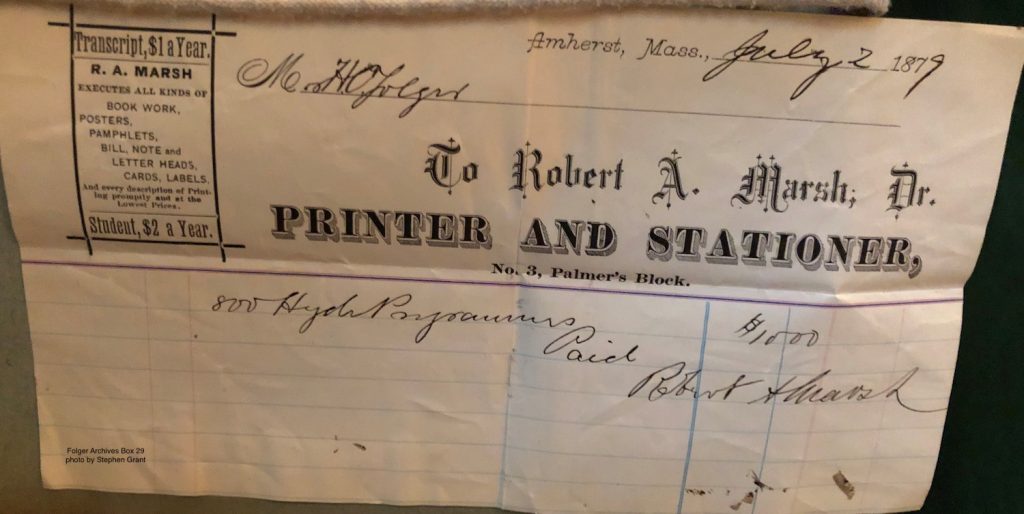

1873 Liberty postal card sent from Amherst, MA on July 1, 1879 to Mrs. H. C. Folger Jr. in Brooklyn, NY. Folger Archives Box 29, photo by Stephen Grant.

Truth be told, it is not a Post Card. It’s clearly labeled at the top center, “U.S. Postal Card.” There’s a difference. A postal card has postage imprinted on the card by a postal authority before it is sold in a post office. The postal value is part of the printed design. The “U.S. postage one cent” value is embodied in the first female to grace a U.S. postage stamp. She is referred to as “Liberty.” The color of the stamp is black. The head is in profile looking left. On the stamp is written “U.S. POSTAGE ONE CENT.” A stern imperative: “WRITE THE ADDRESS ON THIS SIDE – THE MESSAGE ON THE OTHER. How different from picture postcards today where you have address and message on the same side.

When Henry Folger was in college, the U.S. postal system was in its infancy. The first U.S. postage stamp was issued in 1847. The first postal card in 1873, when President U. S. Grant (no relation) after much hesitation approved the measure. For me, a collector, feasting my eyes on a first-generation postal card in the Folger collection is a huge thrill.

Let’s direct our attention to the postmark, “Amherst Mass Jul 1.” In 1879 the dummies in the Amherst post office on North Pleasant St. do not yet have a rubber stamp that includes the hour of mailing OR the year. How unhelpful!

The card is addressed to Mrs. H. C. Folger Jr. at 72 Quincy St. in Brooklyn. That address is expected because it’s where Henry’s parents live. I have stood in front of 72 Quincy. In 2009 I took me a local guide and walked around his Brooklyn neighborhoods; and where his parents lived, and Emily Jordan, his wife-to-be.

Renovated modest two-story free-standing 72 Quincy St., Brooklyn, NY, 2009. Photo by Stephen Grant.

Now let’s turn the card over.

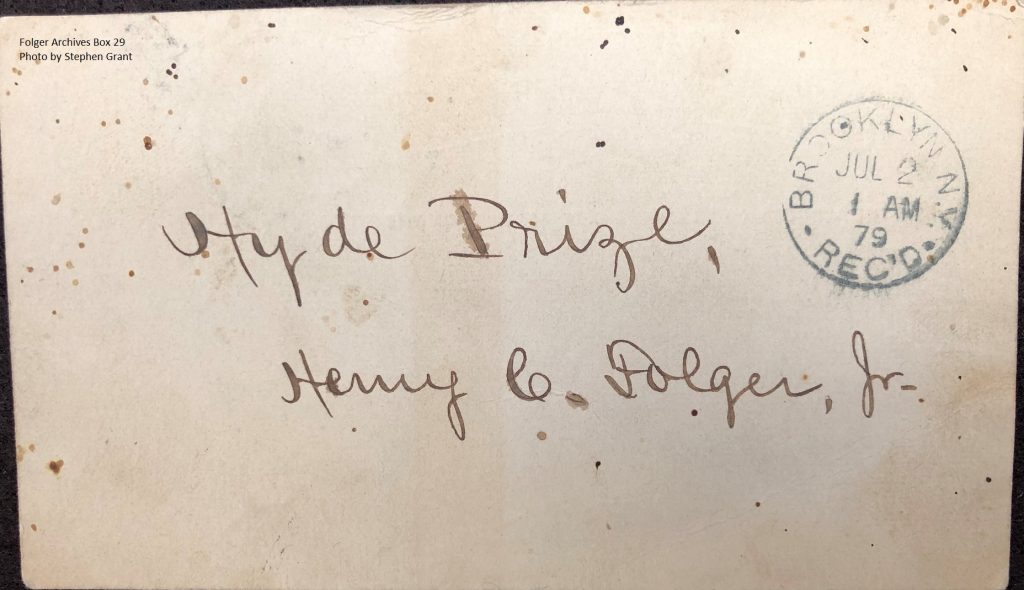

Handwritten message and signature on 1873 postal card received in Brooklyn on July 2, 1879. Folger Archives Box 29, photo by Stephen Grant.

Luckily, postal clerks in Brooklyn have their act together, putting to shame their Amherst counterparts. The postmark reads “Jul 2 79,” so we have the year. Do we really believe the clerks were burning the midnight oil with a hand cancel at “1 AM?”

Very few postcard messages are as laconic as two words. Henry’s message “Hyde Prize,” however, could not have been richer in significance. I need to give you collators some context. The Hyde Prize for Oratory was named for Henry D. Hyde, Amherst class of 1861. A prominent Boston lawyer and long-time trustee of the college, he established the Prize in 1870. It was discontinued in 1931, and now few people have heard of it. Oratory prizes were hugely important on college campuses in the late 19th century.

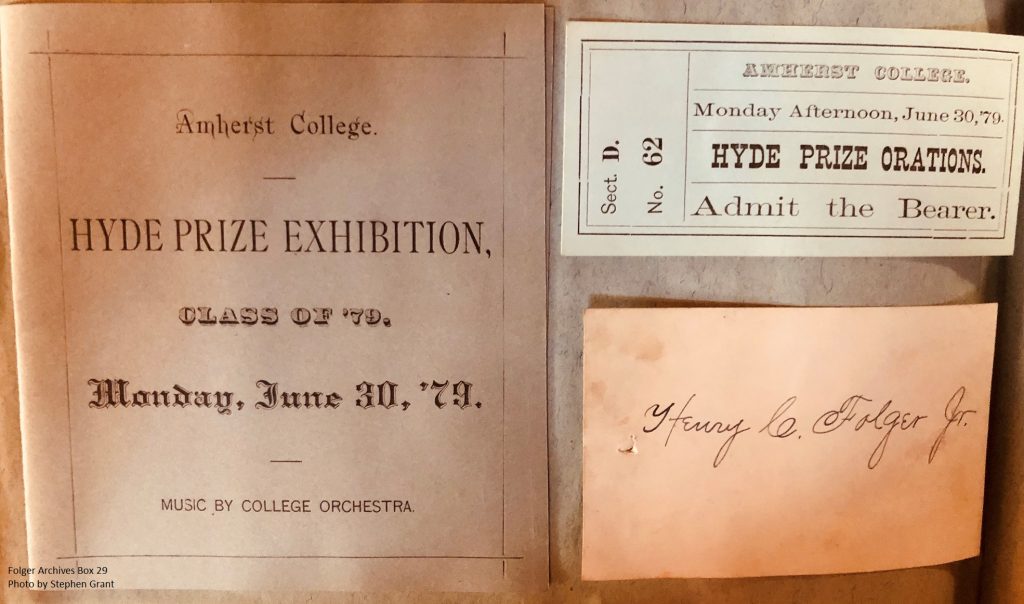

A Hyde page from Henry Folger’s college scrapbook. Folger Archives Box 29, photo by Stephen Grant.

Mon., June 30, 1879 was the big day for the Hyde competition. Henry’s college scrapbook devotes an exorbitant amount of lines to the event. The Prize merited a special exhibit and brought out the college orchestra. Tickets were printed with seat assignments; Henry’s was Sect. D. No. 62. Does this ticket remind anyone of another ticket? Three months before, Henry had bought a similar ticket to hear Ralph Waldo Emerson deliver his last address at Amherst. For this event that so marked Henry, he sat in Sec. A, No. 33 in the same College Hall.

On June 25, Henry had written to his mother, “There are just two fellows in the class who have two orations and Folger is one of them. However it is more chance than merit. If I should take the Hyde for which there is just about one chance in six, it would be the best thing that I have done in my college course” (Folger Archives Box 21). The “best thing”; Folger doesn’t use superlatives lightly.

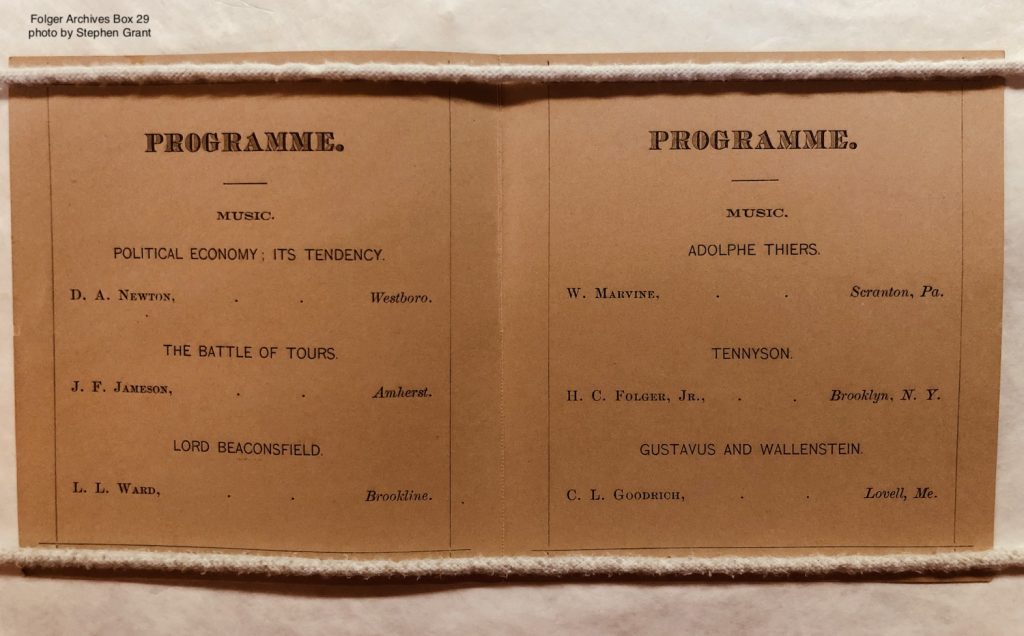

Names of orators and their subjects in Hyde Prize program of 1879. Folger Archives Box 29, photo by Stephen Grant.

How did Folger calculate that his chances of success would be one out of six? We know that he often thought in mathematical terms. The program gives the names of the six orators, the towns they come from, the subject they will address, and when the musical interludes will take place. Candidate Franklin Jameson stands out to me. As first in his class (by contrast, Folger ranked fifth), Jameson was valedictorian. His career included being director of the department of historical research at the Carnegie Institution in Washington, DC, and chief of the manuscripts division at the Library of Congress. Perhaps more than anyone else, Jameson convinced Folger to drop the other sites he was considering and build his Shakespeare library in the nation’s capital.

In Folger’s day an important portion of the curriculum was devoted to declamation. The Free Dictionary defines declamation as “a speech from memory with studied gestures and intonation as an exercise in elocution or rhetoric.” How did Folger fare in his declamation classes? His transcript gives us semester grades: freshman 100, 98; sophomore 98, 98; junior 100, 100; senior 100, 100 (Folger Archives Box 21). With that stellar academic record, who on earth could have been surprised when Henry nailed the Hyde? Folger won with his oration on Tennyson and took home $100, a sum which would have paid for a full year’s tuition. He paid out the first $10 to buy copies of the Hyde program. How many? Eight hundred! What he did with them I know not; likely he shared widely with acquaintances the pride of accomplishment. Henry did not win every prize at Amherst; he lost the Shakespeare competition of all things. Emily joked that her husband became a Bard devotee out of pique.

Astounding Folger purchase when he graduates. Folger Archives Box 29, photo by Stephen Grant.

We can imagine how satisfied Henry would be getting on the train to return to the family in Brooklyn in early July. But wait just a minute! On his postal home, Henry is in Amherst writing to his mother in Brooklyn, right? But she isn’t Mrs. H. C. Folger Jr.; she’s Mrs. H. C. Folger Sr. In 1879 there IS no Mrs. H. C. Folger Jr. The 22-year-old student is Henry Folger Jr. His father is Henry Folger or Henry Folger Sr. as I often call him in my biography. Henry Folger Jr. won’t marry until 1885. He hasn’t even met Emily yet. “Our” Henry goes by the name of Henry Folger Jr. or H. C. Folger Jr. until his father dies. From Jan. 21, 1914 onward, he drops the Jr.

Both sides of the card are indubitably in Henry’s handwriting. My reading of it is that by adding the “Mrs.,” Henry is having some fun! Think of the celebration in the Folger household when the eldest child returns to his parents, his brothers and sister, with a B.A. degree. What a model he is for his siblings! Neither Folger parent had been to college. Henry is adding levity to the occasion. Who in the family was the first one to catch it, I wonder? Not very much appears in the Folger story regarding Henry’s sense of humor. Can one imagine the Folgers guffawing as they pass this postal card around the dinner table? Perhaps not. Henry’s humor is on the understated side.

How else could one explain the Mrs. H. C. F. Jr.? He was pooped and couldn’t think straight? Some evidence does exist. On June 29, Henry writes his Mom, “If I am very tired will wait here till Saturday and so may not reach Brooklyn until sometime Sunday” (Folger Archives Box 21). We’ll never know.

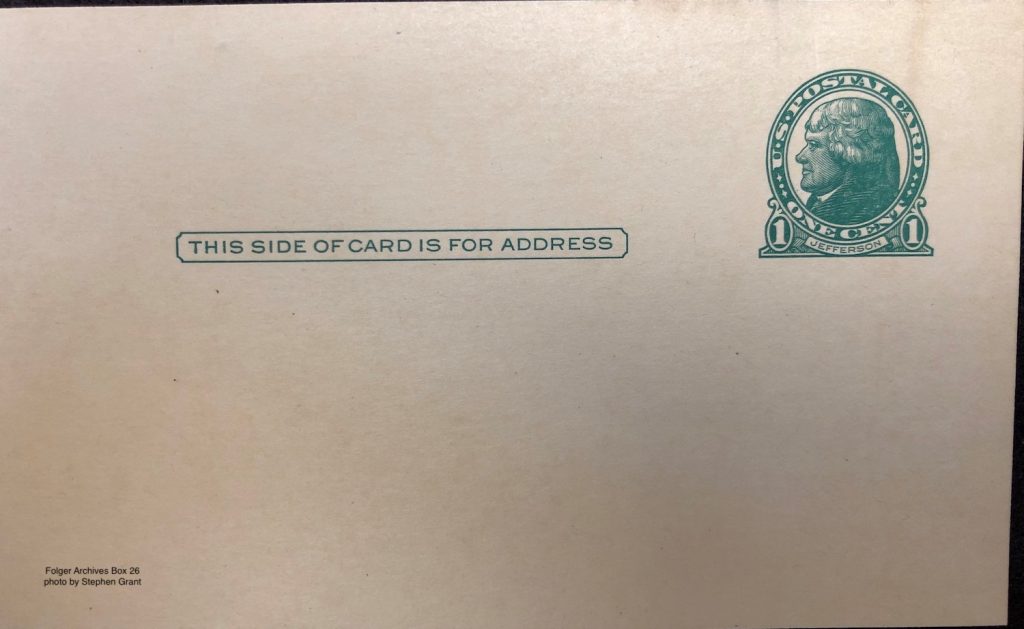

Postally unused 1913 Jefferson postal card. Folger Archives Box 26, photo by Stephen Grant.

Fellow collators, don’t think of postal cards as antediluvian artifacts. Why, I had a stack of this 1913 postal in my desk drawer in 1950. It’s the proverbial “penny postcard.” Received them. Sent them. In 1952 I had to lick and affix a one-cent stamp to the card because the postage rate had gone up. The color of the stamp is green. The Jefferson head is in profile looking left. On the stamp “U.S. POSTAL CARD ONE CENT JEFFERSON” has replaced “U.S. POSTAGE ONE CENT.” In the later card the European design flourishes have disappeared. It is less artsy. It is stark; time is money. The message “THIS SIDE OF CARD IS FOR ADDRESS” no longer includes the imperative “WRITE.” The Jefferson-head postal card was issued in 1913. It took four decades before the U. S. postal authorities deemed that a correspondent could figure out where to write the message without being told.

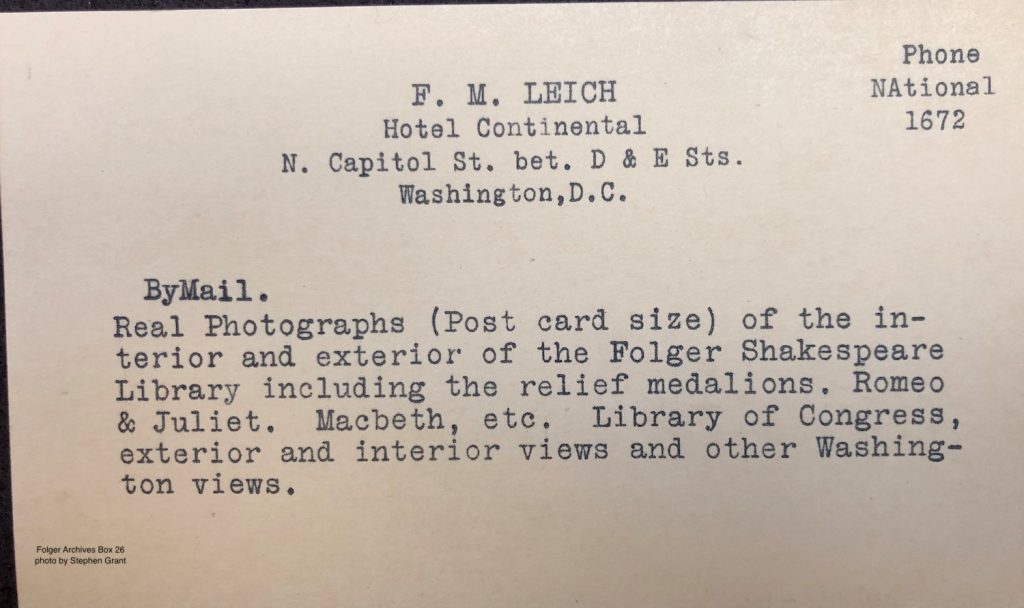

Typewritten message on other side of postally unused 1913 Jefferson postal card, 1933. Folger Archives Box 26, photo by Stephen Grant.

A lot of technological advances occurred between 1879 and 1913 when this postal card was issued. We had the invention of the typewriter. The use of this postal card with typewritten message is commercial. Frances M. Leich had a concession stand in the Hotel Continental on North Capitol St. with an unobstructed view of the Capitol. This is Washington, DC not only before zip codes, but you asked a telephone operator for a party’s number by giving two letters followed by four digits: NA 1672. Leich was the first merchant to sell picture postcards of the Folger Shakespeare Library, both exterior and interior views. The vendor curiously calls the marble bas relief sculptures on the north façade “medalions.”

When my family of four drove from New England to Washington DC in 1951, we stayed in the Hotel Continental. I had a little pocket money, and spent some of it to buy a picture postcard of the hotel at that very concession stand. I kept it in a former box of chocolates until 2012 when I gave it to my grandnephew to begin his postcard collection.

(This post originally appeared on the Folger Shakespeare Library’s research blog The Collation on Aug. 1, 2019)

COMMENTS:

-

Gail Kern Paster

This is delightful stuff about our founders that only you could write–given your twin expertise here in the Folgers’ lives and the history of postcards. -

Annie Groer

I’m a longtime fan of both the literary treasures within the Folger, and its stunning Greco Deco exterior architecture. A friend alerted me to Stephen Grant’s scholarly yet utterly charming tale of Henry Folger and this history of post(al) cards, as well as the declining art of collegiate oratory. What a treat. Many thanks for this special Collation. -

Thomas Edwin Woodhouse

You make the history of the postal card almost as interesting and entertaining as is your story of the Folgers. Deltiologist indeed! -

Robin Swope

A wonderful, charming story about Mr. Folger from his days at Amherst. The pictures at the Folger show a rather solemn looking man who was all business. Your post gives us a different, much more personal insight into Mr. Folger. We rightly focus on the work he and Mrs. Folger did to put together an amazing collection and build the Library, but the two of them as individuals sometimes get lost. As a docent at the Folger it is always so nice to have stories to share with our visitors. This post will be added to the stories I share. Our visitors thank you! -

Werner Gundersheimer

Stephen Grant has explicated one of the enduring mysteries — the subtle variation between post cards and postals. One had assumed that this was a distinction without a difference, but no! Suddenly, a grandmother’s words make sense: “Send me a postal” didn’t necessarily mean a post card at all. Folger’s card to his Mom conforms to the minimalist requirements of reportage to parents. “Hyde Prize” says it all. A taciturn fellow, but not without a sense of accomplishment, and perhaps a touch of ego. And what about those 800 copies? HCF won the prize in his senior year, and was about to leave the Amherst community. That he shelled out ten precious bucks for all those useless “programmes” poses another enduring mystery, this one perhaps insoluble.A strong candidate for the most beautiful Amherst College postcard ever is the 1912 image of the inauguration of President Alexander Meiklejohn, the most distinguished educator to hold that office. The card, in full color, shows the robed faculty in procession across the quadrangle. Like most of the American souvenirs of the period, it was made in Germany, a practice that ended soon thereafter, for obvious reasons. Might Folger been there that day? What about it, Stephen?

Stephen Grant

In lieu of a positive answer, Werner, this exchange between the two men:Ltr 6/2/14

Dear Mr. Folger

I am very glad to know that you can be with us on Commencement day and that you will present yourself to receive the degree [honorary degree of Litt.D)] which has been voted by the trustees. Ever since your reply to my remark about the Marsden Perry collection I have been hoping for a chance to say something to you under circumstances which would make a reply impossible. I think my opportunity has come. With kindest regards, Alexander MeiklejohnLtr 2/5/15

Dear President Meiklejohn,

Mrs. Folger and I wish to extend to you and Mrs. Meiklejohn our sincere sympathy for you in the loss of your father. I notice by the newspaper reports that he was of the same age as my own father, who died a year ago. I was about sending you a letter when I saw the notice of your father’s death, to ask you and Mrs. Meiklejohn whether you could arrange to spend a night with us in Brooklyn the latter part of April and attend the Opera with us. . . Henry C. Folger - Debby Applegate

I cannot claim so lofty a title as deltiologist, but I am a proud lifelong deltiophile – just learned that word, thanks for that! – I love this new column of yours. An excellent combination of antiquarian expertise and gossipy historian, my favorite combination as it happens. I like the warm tone & sharp touches of humor although, my dear Steve, oughtn’t we be a bit more complimentary toward those hardworking postal-workers who make it all possible? Maybe the village postmaster in frugal Amherst couldn’t afford a rubber stamp!

Stephen Grant

Fair point.

-

Rhea DeStefano

Wonderful read on the history of postcards. Certainly a rarity to receive one nowadays. -

Kevin Mei, Folger Fellow Jan ’16

Thanks for sharing! I enjoyed reading this. It’s amazing to see how much can be learned from postcards and liked learning about the Hyde Prize. I wish oration and declamation were still formally prioritized. And always fun to hear that $100 could’ve paid full tuition college for a year.

COMMENTS:

CONNECT

0 Comments