“I thoroughly enjoy your Folger updates. I resonate with Uncle Henry and Aunt Emily’s pleasure at long and slow Atlantic sailings. Two years ago I crossed on Wind Star, a motorized sailing ship for 148 passengers nonstop for 15 days. I loved sitting on deck reading and experiencing the sea air and water. “

Henry Folger Cleaveland Jr

“Stephen, this is a wonderful post. It is one of your best! Thank you for sending it.”

Peter M. Folger

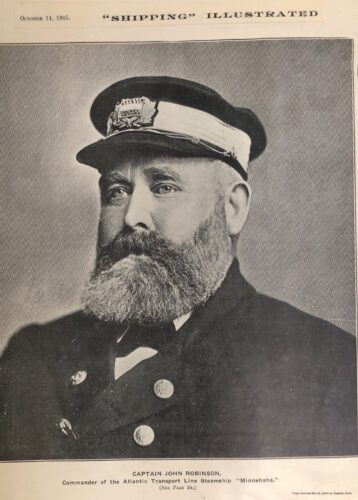

Rosy-cheeked and white-bearded poet, painter, and shipmaster John Robinson of Watford, Hertfordshire was a commanding presence on the bridge of the steamship Minnehaha from 1900 until he retired from the American-owned Atlantic Transport Line due to poor eyesight in 1907.

Fig 1. British Sea Captain John Robinson in Magazine Article, 1905 Folger Archives Box 42, photo by Stephen Grant

His seafaring career spanned a half-century, starting as cabin boy at a shilling a month. In his forty-plus years at sea, he never spent more than three consecutive months ashore. When the above picture appeared in Shipping Illustrated on Oct. 14, 1905, Robinson had made 60 round trips on the Minnehaha after bringing her out from Belfast on her maiden voyage.

When the Folgers met him on board, they discovered a commander not only with extensive seamanship and a genial disposition, but a thorough knowledge of Shakespeare. Other illustrious personalities who traveled on the Minnehaha and became close friends with Capt. Robinson were Susan B. Anthony, Albert Pinkham Ryder, and Mark Twain.

“Capt. Robinson, with whom we crossed the ocean many times,” Henry wrote a friend, “said Shakespeare was an admirable and experienced sailor.” Henry continued, “There have been books written to prove he was a Freemason, and the last that I have seen is one by a barber proving Shakespeare was an expert in the sartorial art” (Folger Archives Box 20). A specialist in every trade, a writer for all people.

Fig 2. British Sea Captain John Robinson Photo, 1906 Folger Archives Black Box 6, photo by Stephen Grant

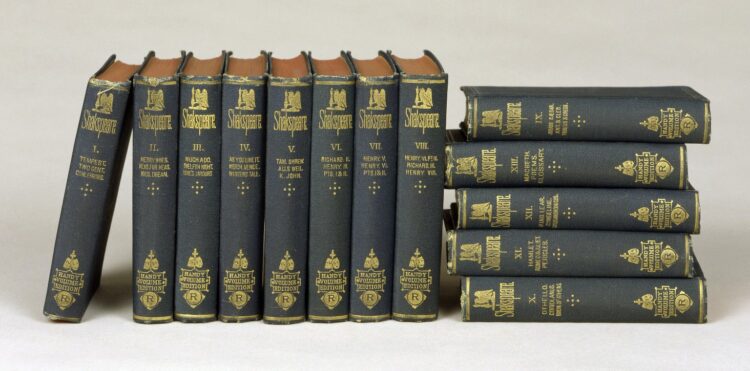

The Minnehaha plied the north Atlantic from New York to Liverpool or London and back. The slow steamer accommodated the Folgers’ desire for a prolonged crossing where, wrapped up in great coats and lounging on deckchairs, they could read, relax, and listen to the surf. They brought along a selection from their 13-volume Routledge “Handy” edition of Shakespeare’s Works.

Fig 3. 13-volume Routledge “Handy” edition of Shakespeare’s Works (PR2754 13a3c Cage). Image from LUNA.

Henry’s favorite play to read on ocean voyages was The Tempest. He wrote in an essay entitled “From Ariel to Caliban”: “It is fragrant with salt spray picked up from wave crests by driving winds. The enchanted isle of Prospero seems to have risen out of the surf’” (Folger Archives Box 30).

The couple looked forward to the Sunday services when stewards made up the choir. The Minnehaha offered spacious suites for 250 first-class passengers. Patrons enjoyed the saloon deck and two promenade decks, while below were crammed automobiles, player pianos, and noisy bovine cargo. After 15 years as one of the most popular single-class ships in Atlantic shipping history, the Minnehaha was converted into a freighter, carrying munitions in WWI. On September 7, 1917, the vessel was torpedoed by a German U-boat and sank.

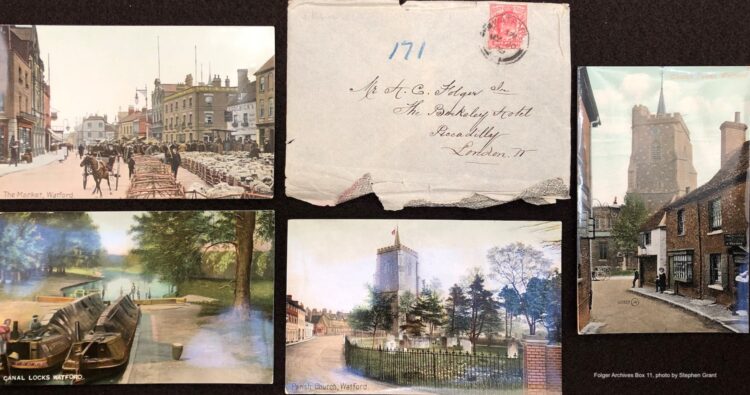

Correspondence between Capt. Robinson and Henry Folger lasted from 1905 to 1922. July 30, 1909 is the postmarked date of an envelope (top center in Fig. 4, below) from Capt. John Robinson in Watford to Henry Folger at the Berkeley Hotel in Piccadilly West.

Fig 4. Four Picture Postcards, One Envelope John Robinson sent to Henry Folger, 1909 Folger Archives Box 11, photo by Stephen Grant

The Folgers had spent a few days treating the Robinsons to Shakespeare plays at Stratford-on-Avon, and would sail back to New York on July 31. The colored postcards, which now reside in the Folger collection, depict the Watford parish church, the market, and the canal locks.

Watford was in the world news as recently as December 2019 when its five-star Grove Hotel in Chandler’s Cross housed the 29 member leaders and their staffs participating in the NATO 70th anniversary meeting. It was “the biggest pre-planned policing operation England had ever seen.” The canals were closed, as were tow paths and roads. Drones were prohibited from flying. A big change from the bucolic tranquility during Capt. Robinson’s days living in Watford.

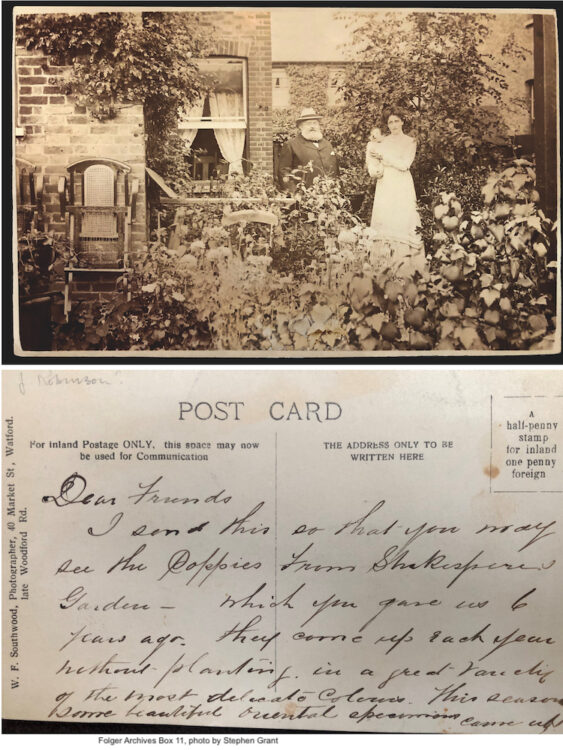

This “Real Photo Postcard” shows Capt. John Robinson’s garden at 13 Cassio Road, Watford, Hertfordshire. The sea captain and his daughter with dog are posing with “Shakespeare poppies.”

Fig 5. Picture Postcard John Robinson sent Henry Folger, 1910, and message Folger Archives Box 11, photo by Stephen Grant

“Dear Friends,” Robinson wrote,“I send this so that you may see the poppies from Shakespeare’s garden—which you gave us 6 years ago. They come up each year without planting in a great variety of the most delicate colours. This season some beautiful oriental peonies came up.”

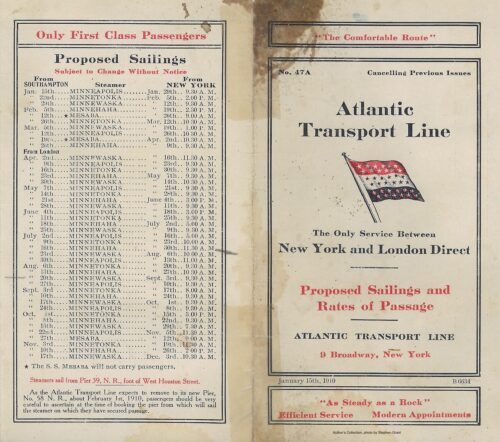

Henry and Emily probably both held in their hands this very schedule #47A of the Atlantic Transport Line issued on Jan. 15, 1910. The folded 3 ½ by 6 ¼ in. document printed in red, white, blue bears two pencil marks as well as stains—Folgers coffee, perhaps?.

Fig 6. Atlantic Transport Line Schedule with stains, 1910 Author’s Collection, photo by Stephen Grant

It was given to me by a Folger grandniece who has since passed away. The July 30 11:30 AM sailing from New York and the Aug. 20 return from Southampton are marked. We read, “Time of passage about 9 days.” The Folgers savored their transatlantic travel and were in no hurry. Here is what Henry wrote Capt. Robinson in May of 1910, “I probably will decide on the ‘Minnetonka,’ as it is hard to think of making the voyage on any other line, especially as changing to another ship would reduce the number of days at sea” (Folger Archives Box 23). The couple booked deck cabin G with private bathroom on the upper promenade deck. For Henry, the offices of the Line were located at 9 Broadway, near his Standard Oil Company tower on 26 Broadway.

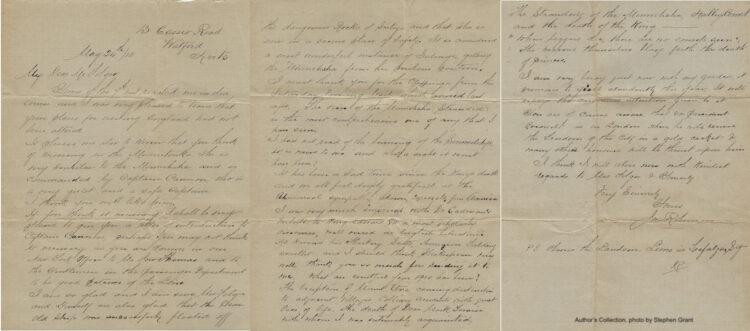

Robinson wrote back to Henry, saying that

“I was very pleased to learn that your plans for residing in England had not been altered. It pleased me also to know that you think of crossing in the Minnetonka, she is very similar to the Minnehaha, and is commanded by Captain Cannon, who is a very quiet and a safe captain. I think you will like him. If you think it necessary I shall be very pleased to give you a letter of introduction to Captain Cannon, perhaps you may not think it necessary as you are known in our New York Office to Mr. Ian Thomas and to the Gentlemen in the passenger Department to be patrons of the Line.”

Fig 7. Letter from John Robinson to Henry Folger, 1910 Author’s Collection, photo by Stephen Grant

He went on to note “What an eventful year 1910 has been!” referring to (among other things) the eruption of Mount Etna, the appearance of Halley’s comet, and the deaths of both Mark Twain and King Edward VII. Robinson then quotes from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Act II, Scene 2: “when beggars die, there are no comets seen, the heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes.”

Throughout his career, Robinson drew sketches and made oil paintings of marine scenes. After retirement, he turned to depicting rural settings. He sent his 12 x 18 ½ oil painting of Anne Hathaway’s cottage to the Folgers for Christmas 1912. The oil executive responded, “You may guess how satisfactory the painting is when I tell you that it has been hung over Hayman’s portrait of Quinn as Falstaff, painted from life and used as the basis of the well-known engraving, and at right angles to Sir Joshua Reynolds’s portrait of Garrick” (Folger Archives Box 23). For the Folger biographer that I am, this letter gave me the only description I ever found of paintings the Folgers chose to decorate their walls at 24 Brevoort Place in Brooklyn. I would have wanted to be invited to the Folgers for dinner, and have Henry show me around their home. The Folger deaccessioned Anne Hathaway’s Cottage painting in 1964 (Folgerpedia, Deaccessioned Paintings, D55), but at least we have Henry’s mention of it!

(This post originally appeared on the Folger Shakespeare Library’s research blog The Collation on June 23, 2020)

COMMENTS:

CONNECT

0 Comments