This post brings alive the launch of my first biography fifteen years ago, on Jan. 29, 2007. My son, Yonel, a transportation engineer, flew in from San Francisco and videotaped my introductory remarks from the podium. My daughter, Sylviane, who designed the book, took the bus from New York City. My sister came from Mass., my cousin from Maine. “Old Home Week” is what my mother would have called it. My father would have been floored. He worked forty-two years in the book publishing business in Boston. He died in 1978, thirteen years before the first of my five books saw the light of day.

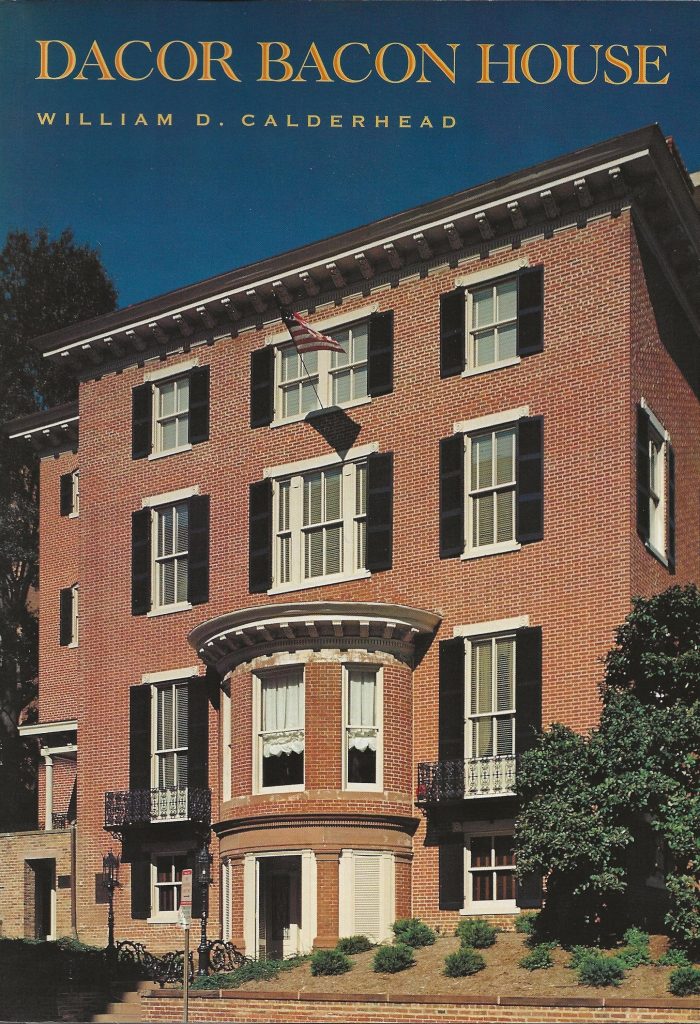

I have been the protagonist of book launches in Guinea, Indonesia, El Salvador, and the U.S. I know of no more historic and elegant venue for a book launch than the DACOR BACON HOUSE at 1801 F Street, NW. It is one of the very few Federal-style homes left in Washington, DC.

Fig. 1. DACOR stands for Diplomatic and Consular Officers, Retired. It is a membership association of foreign affairs professionals. Bacon refers to the Bacon family, in particular to Virginia Bacon, the last resident of the house until her death in 1980, after which the private home transitioned to the offices of a foundation. The DACOR BACON HOUSE accommodates headquarters and programs of a 2,300-member organization.is. In 1999, William D. Calderhead and the DACOR BACON HOUSE Foundation published this 159-page history, of which this is the cover.

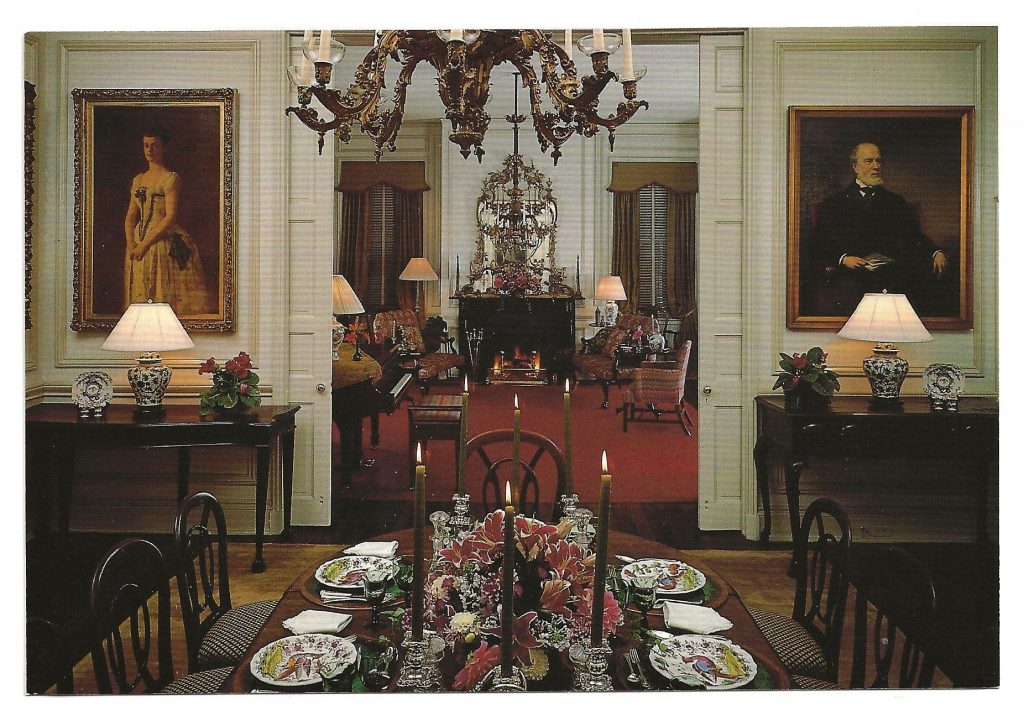

Fig. 2. A postcard depicting the dining room and drawing room of DACOR BACON HOUSE when it was a private home (1815–1980)

The Jan. 29, 2007 book launch held at DACOR featured the biography of Peter Strickland (1837–1921) of Connecticut, who became the first American Consul (1883–1905) to French West Africa with residence in Senegal

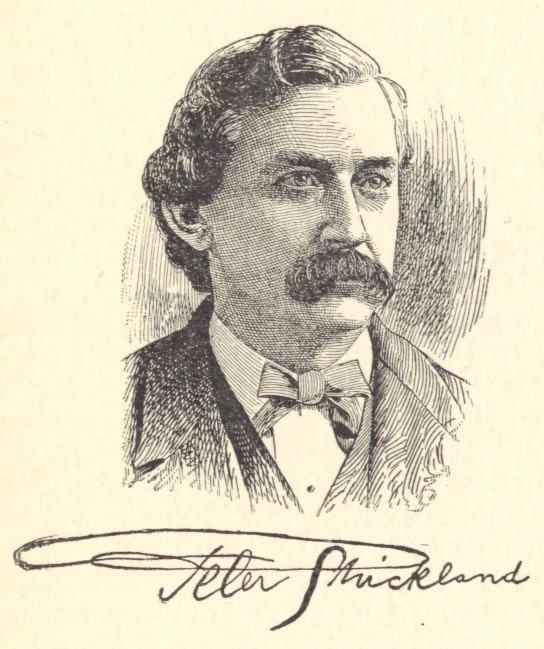

Fig. 3. Only known image of Sea Captain Peter Strickland (1837–1921), first U.S. Consul to Senegal (1883–1905)

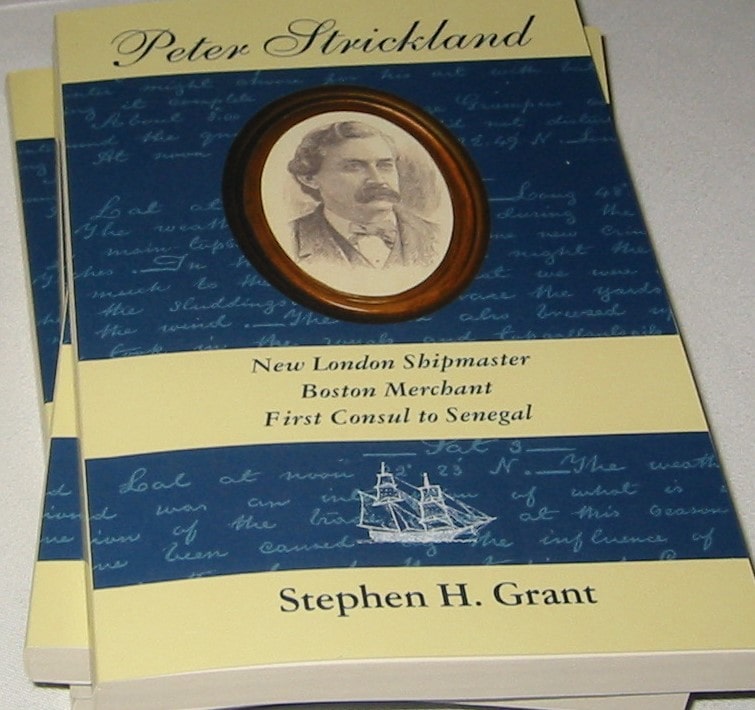

Fig. 4. Book to be launched, the first biography of the first American Consul to Senegal

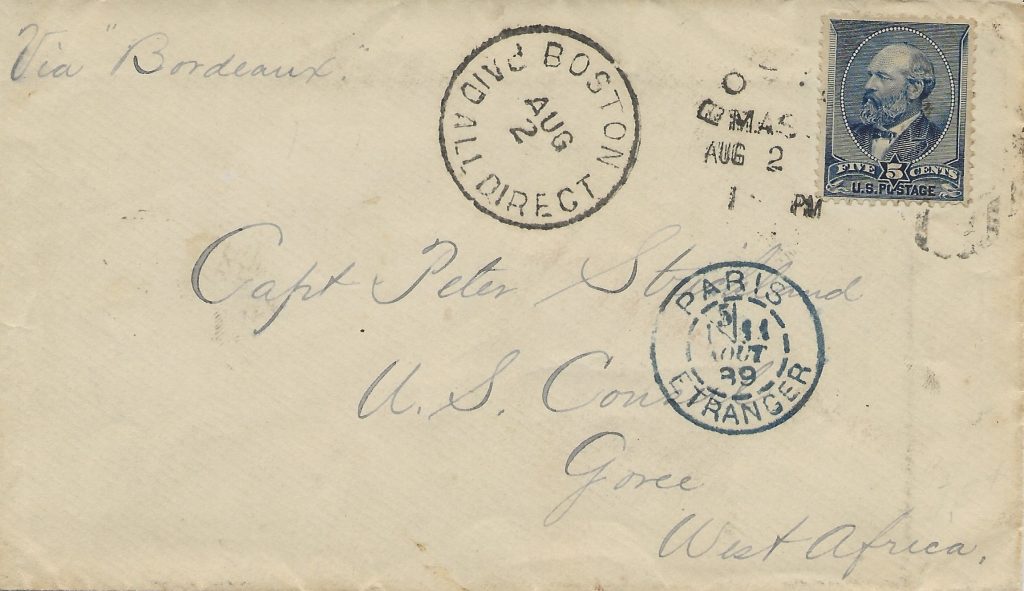

Fig. 5. Envelope I found in 1999 on eBay sent from Boston (where I was born) in 1889 to Consul Strickland in Gorée, West Africa

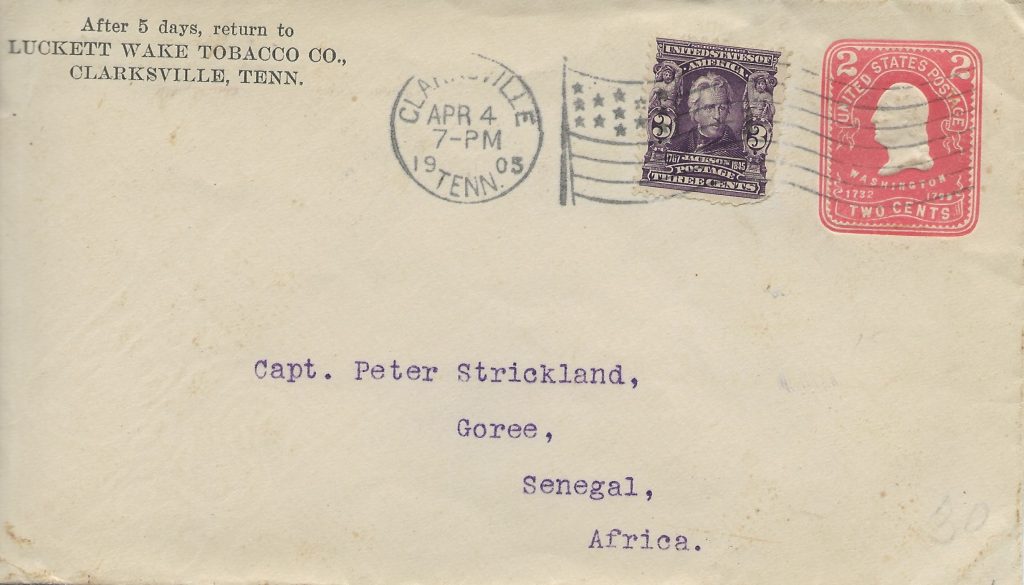

Fig. 6. Envelope from tobacco firm in Tennessee sent to Capt. Strickland in Gorée, West Africa in 1905

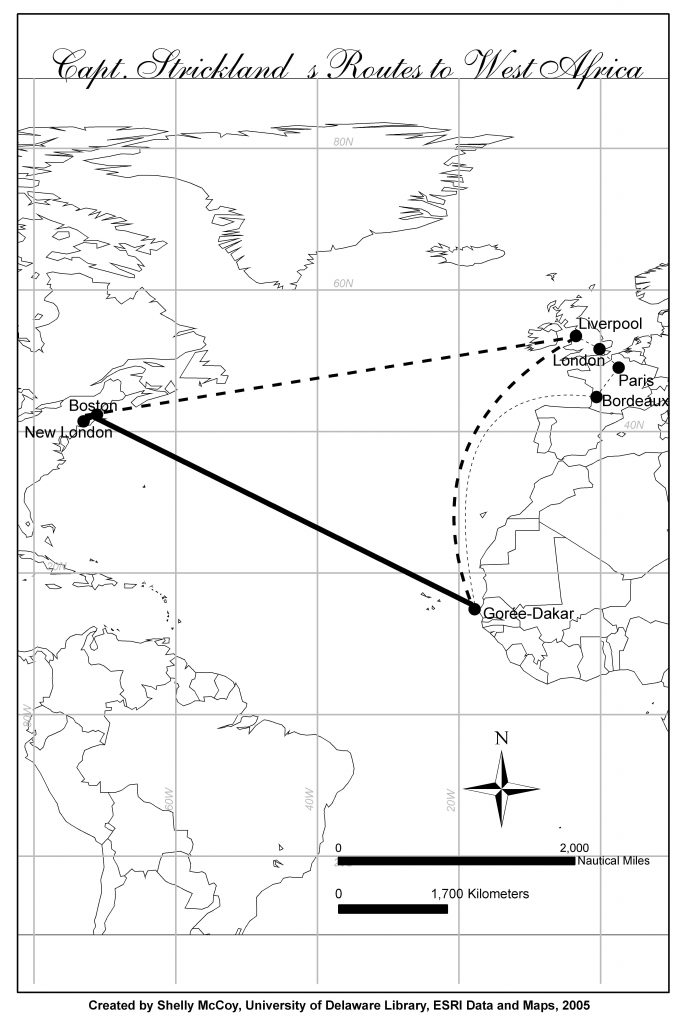

Fig. 7. Captain Strickland’s routes to West Africa from Boston, Mass. and New London, Conn.

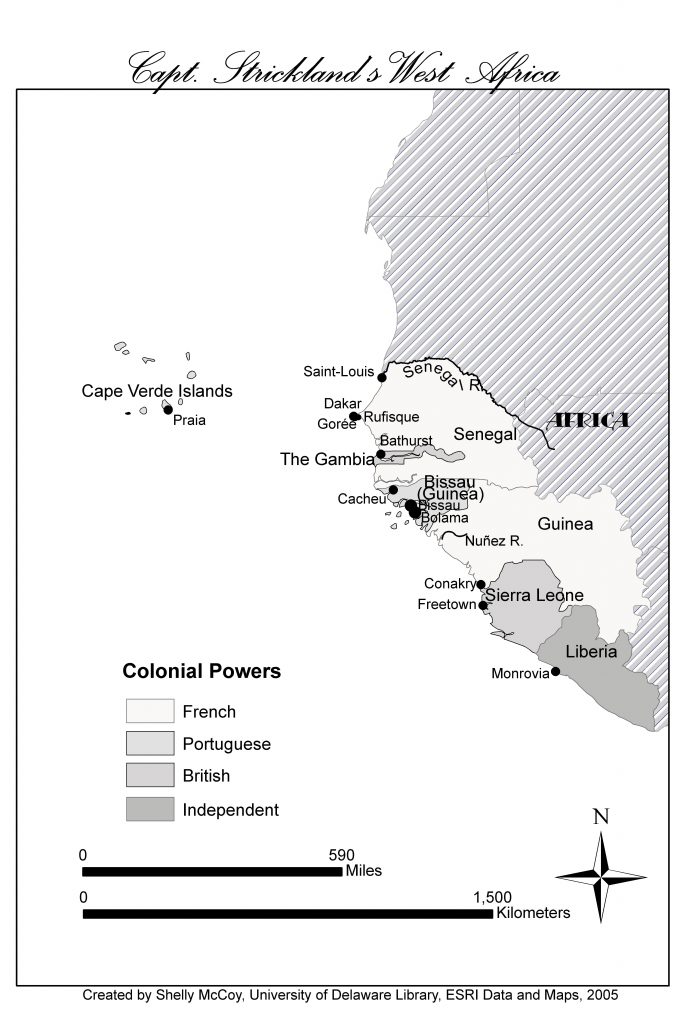

Fig. 8. Captain Strickland’s territories visited in West Africa for commercial or consular missions

ADST stands for the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. It is a United States non-profit organization established in 1986 by retired Foreign Service officers. It produces and shares oral histories by American diplomats and facilitates the publication of books about diplomacy by diplomats and others. Its Foreign Affairs Oral History program has recorded over 2,500 oral histories and continues to grow; its book series includes over 100 books. ADST is located on the campus of the Foreign Service Institute in Arlington, Virginia. Since 1995, DACOR has partnered with ADST to sponsor the publication of books crowned by a book launch on DACOR’s historic second floor.

A year before the book launch––on Jan. 31, 2006––ADST staff wrote an abstract of the Peter Strickland manuscript:

Stephen Grant’s biography of New Englander Capt. Peter Strickland (1837–1921) is based on original documents, consular dispatches, ship’s logs, over 2000 letters researched in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, and Senegal from 2000 to 2006. After teaching school in New London, Connecticut, Strickland left his farming family in 1852 and embarked on merchant voyages along the east coast and to the Caribbean, South America, and Europe. By his early twenties, he had become shipmaster and agent for Boston shipowners.

In a book Strickland published in 1873, A Voice from the Deep, which Grant cites, he lamented the difficult life sailors led, exploited by shipowners and officers, shipping agents, boarding masters, and consuls. He argued unsuccessfully for a federal subsidy for sailors, who risked their lives to provide better off Americans with needed and exotic imported goods.

In 1883, Strickland accepted a State Department proposal that he open the first U.S. consulate in French West Africa, in the colony of Senegal. The captain would not receive a salary but could keep fees charged American vessels visiting Senegalese ports and continue to practice his import-export trade. He established his consulate and residence on the former slave island of Gorée, where he lived until he resigned from the consular service in 1905. He retired to Dorchester, Massachusetts, and the life of a gentleman farmer. He and his wife had four children; none married, and the family line died out.

During his long stint as consul, Strickland recorded the cargoes unloaded and loaded by the 78 American sailing vessels that voyaged from New England to Senegal. The main U.S. export was leaf tobacco from Tennessee and Kentucky, followed by wood products from New England. Blocks of ice from the Kennebec River wrapped in sawdust were shipped across the Atlantic to be used for refrigeration in Africa. Peanuts from Senegal constituted the main West African import into New England, followed by animal skins and gum products. In Capt. Strickland’s first voyage to Senegal in 1864, the skins he brought to Boston were made into shoes worn by Union soldiers.

Strickland’s life and writings are significant for several reasons. He provided the only American record of consular duties and the decline of American trade in francophone West Africa over the period 1880–1905. A conscientious and religious self-made man, he taught school, published a book on behalf of sailors, crossed the Atlantic 100 times, and survived epidemics of yellow fever and cholera in Africa. In an amazing feat, he wrote a daily journal rich in entries from age 19 to 83.

Grant’s 60,000-word book recounts the man’s life chronologically. In addition to 280 endnotes, the work contains numerous illustrations, including old picture postcards, envelopes written to Strickland in Africa, letters Strickland wrote found in the Senegalese archives, drawings Strickland made of sailing vessels, and a photo of President Clinton visiting the former U.S. Consulate on Gorée to commemorate the earliest American-Senegalese relations.

Fig. 9. DACOR’s three chandeliers––first gaslit, then handlit––were made in Philadelphia around 1840

Fig. 10. Anne Kauzlarich, DACOR Executive Assistant, welcomes Fatou Kader and Cheik Cissé. Fatou was Librarian at USAID/Dakar and Cheik, her husband.

Fig. 11. Anne Kauzlarich greets Steve Lauterbach and his wife, Marie-Paule Lauterbach. Steve was a Public Affairs officer; Marie-Paule a French teacher at FSI.

Fig. 12. On Anne’s right is Gordon Thompson; on her left, Colin Boocock. Gordon’s wife Margery Thompson is Publications Director at ADST. Colin was a specialist in mining and environmental management.

Fig. 13. As host, the DACOR President––here the late Michael Ely––introduced Kenneth L. Brown, ADST President, who introduced the speaker

Fig. 14. Author Stephen Grant spoke from the podium. His son Yonel filmed the event. Behind the speaker is an English giltwood mirror built around 1760. On Yonel’s left is Lucien Moreau, a World Bank economist.

Fig. 15. Steve Honley, Editor of the Foreign Service Journal

Fig. 16. DACOR Executive Director, Richard McKee, converses with Catherine Lincoln

Fig. 17. Author conversing with Diane Bodeen, Choral Director and wife of former Public Affairs officer, Virgil Bodeen. In the middle is Anna Lawton, Publisher of New Academia Publishing that published Peter Strickland. On Anna’s left is Dane Smith, former Ambassador to Guinea and then to Senegal.

Fig. 18. Veda Engel, former Foreign Service officer, is speaking with John Pielemeier, former USAID Mission Director. In the middle is Margery Thompson, ADST Publications Director.

Fig. 19. On the far right, Journalist, Author, and Activist Sam Smith

Fig. 20. Former Ambassador to Sierra Leone, the late Arthur Lewis, and Jay Silberg, Attorney

Fig. 21. Architect Robert Schwartz and his wife, Carol Schwartz, Property Manager

Fig. 22. The late Anthropologist Marilyn Merritt served as a Docent in the DACOR BACON HOUSE

Fig. 23. Fatou Kader was USAID Librarian in Dakar, Senegal, attending with her daughter Jamila

Fig. 24. Cheik Cissé, a friend from Senegal, congratulates the author

Fig. 25. Former USAID Mission Director Sam Rea greets Ambassador Abdoulaye Diop from Mali, who went on to become Malian Minister of Foreign Affairs

Fig. 26. The author’s sister Corie, cousin Priscilla, and daughter Sylviane Grant

Fig. 27. Graphic designer Sylviane designed the cover of the Strickland biography; her brother, a transportation engineer, was launch videographer

Fig. 28. Abigail Wiebenson––the author’s partner––was longtime head of the independent Lowell School in Washington, DC

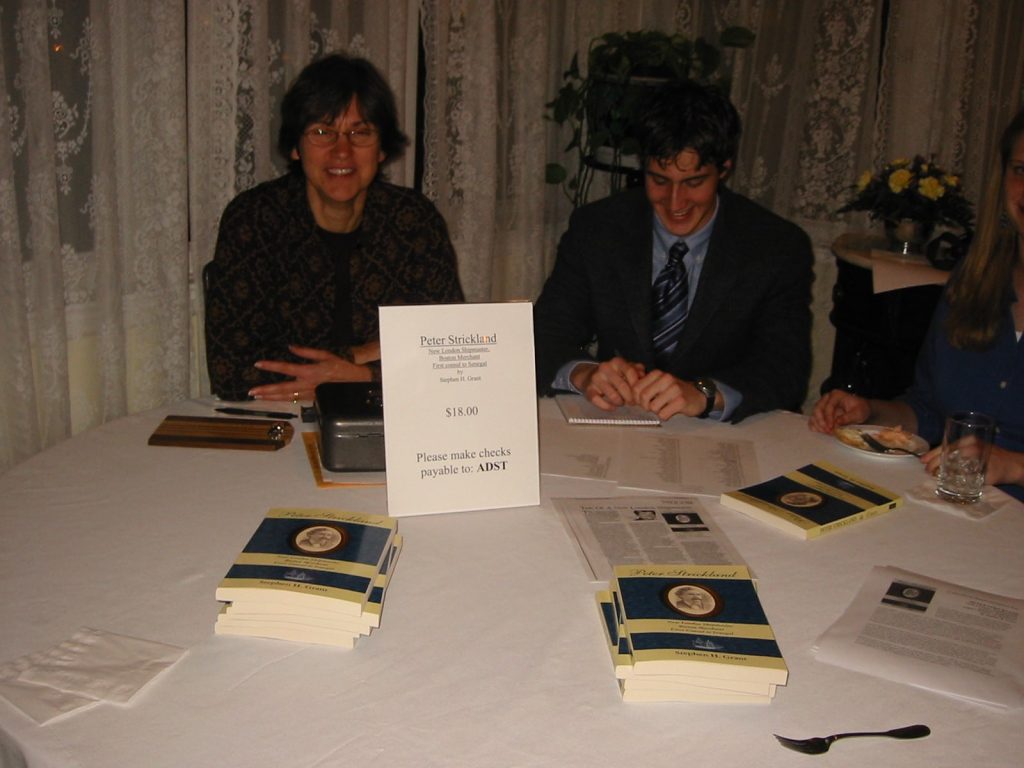

Fig. 29. ADST Business Manager Marilyn Bentley with the help of interns sells and takes orders for the featured book

Fig. 30. Joyce Leader––former Ambassador to Guinea––in 2020 published From Hope to Horror about the Rwanda genocide

Fig. 31. Bintou Condé of the Embassy of Guinea in Washington, DC

At an ADST/DACOR book launch, the author is introduced and says a few words before opening up the discussion for questions or comments. Among my comments were these:

“At the outset of my research before writing the first biography of Peter Strickland, I had the notion that he might have set some record being a consul for over 23 years in one post. These days such longevity would be unconceivable. Far from it. The Office of the Historian of the State Dept set me straight: Horatio Jones Sprague served as consul to Gibraltar from 1848 until 1901: 53 years.”

“Strickland wrote a total of 272 dispatches to Washington. They are all available at the National Archives and you can order them on microfilm as I did 6 years ago when I was working for USAID in El Salvador and began my research for this book.”

“At age 19, Strickland started a daily journal. His last entry was at age 83. Please raise your hand if you know of someone else who kept a diary for 64 years.”

“I want to read you one brief diary entry from 1864. Strickland was 27 years old. ’One month ago today I left my home in New London to go I then knew not whither but I now find it was for Africa. It does not seem so long but time in certain circumstances flies very quickly. To look ahead, a lifetime seems a long period and in some cases it may no doubt seem long. But if I am permitted to live to old age, and look back on my lifetime as I do now and in the same light I shall no doubt think it has been short. I shall think how “like a hurried dream” it has all been.’”

At this point in the proceedings, I thanked a few people; my children, Sylviane and Yonel Grant. Then Anna Lawton, Publisher, New Academia Publishing; and Marilyn Bentley, ADST Business Manager. Finally, ADST Publications Director, Margery Thompson, for “her expert guidance of authors through the publication process.”

Peter Strickland Book Launch at DACOR BACON HOUSE

COMMENTS:

4 Comments

Submit a Comment

CONNECT

How lovely to witness the pomp and circumstance of the initial launch of a project that has come to take such an important place in my family’s history! My second cousin, three times removed, would have been pleased with the gravitas that accompanied the revelation of his life.

Wow! Awesome event. Thanks for sharing.

A memorable evening

You made my father so happy by writing and publishing this book on our ancestor. Thank you, Stephen!