“Stephen, thanks for this fascinating research. The images are particularly evocative of that time and place. As you well know, John D. Rockefeller sent missions to potential acquisitions or partners from the very beginning of Standard Oil, so it’s not surprising that practice continued under Henry Folger and his cohort. You were entirely right to expand the scope of your book past the Folgers as collectors so we could learn about their lives in full.”

Eric Johnson

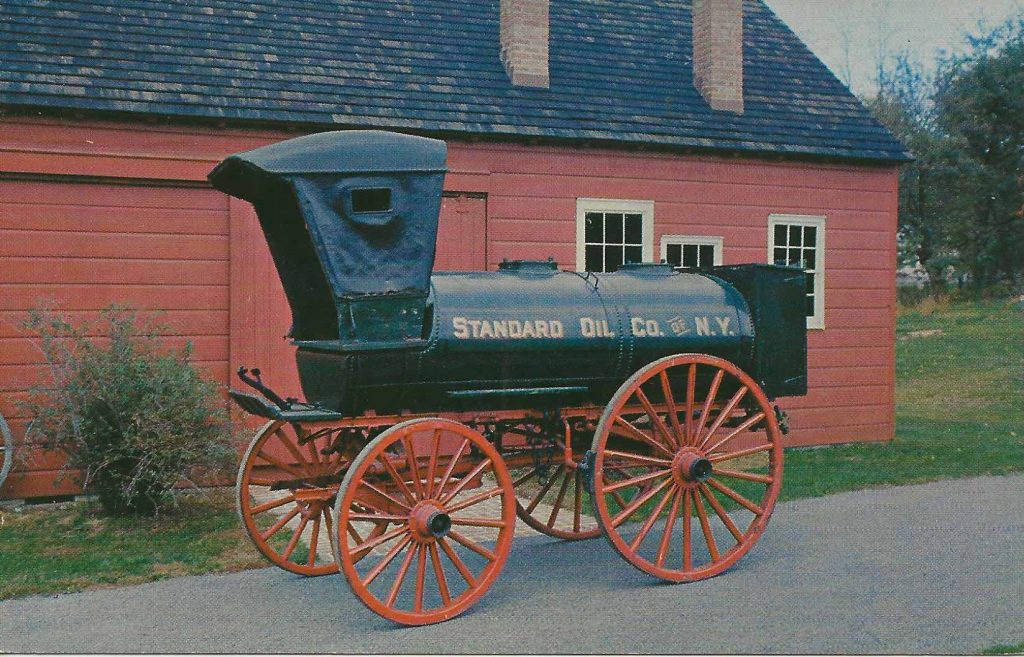

Standard Oil Co. of New York delivery wagon, c1900

Author’s collection, photo by Stephen Grant

A decade ago when I was determining angles to consider in approaching Collecting Shakespeare: The Story of Henry and Emily Folger, some readers—perhaps at 3 pm Folger tea—recommended I write only on the Folgers as collectors. As I was writing the very first biography of the couple, I finally decided it made little sense to focus on how they spent their money at the neglect of how they earned it in the first place. Had Henry followed his strongest suit and become a math teacher, there goes the Shakespeare Library out the window. So here we go with some info about key Standard Oil Company personnel.

On Dec. 8, 1911, Standard Oil Company founder John D. Rockefeller Sr. resigned the presidency and directorship of the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, that later became Esso and then Exxon. Yes, he made way for younger men, but he wasn’t going anywhere. John D. Rockefeller would not decide to die until a quarter of a century later, in 1937 when he was almost 98 years old. Three of those younger men were Henry C. Folger (1857–1930), Alfred C. Bedford (1863–1925), and Walter C. Teagle (1878–1962). At the time, Folger was 54 years old, Bedford was 48, and Teagle was a mere 33. These Standard Oil executives were born in three different decades. They all shared the same middle initial; I call them the “Three Cs.”

As for the pedigrees of the Three Cs, try this on for size. With a law degree, Folger in 1911 was president of Standard Oil Company of New York (later Mobil Oil Corporation) and would be its chairman of the board from 1923 to 1928. He was director and treasurer of Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, as well as being on its executive committee. Bedford was a specialist in natural gas who would be promoted from treasurer to president of Standard Oil Company of New Jersey in 1916 and serve as its board chair from 1917 to 1925. Trained as a chemist, Teagle was a specialist in foreign and domestic marketing. He was vice-president of Standard Oil of New Jersey. He would serve as president of Standard Oil Company of New Jersey from 1917 to 1937, then board chair until 1942. Teagle was six foot three, weighed 250 lbs., and smoked a Havana cigar through an amber holder. He was known for his booming voice and unblinking stare.

Before making large investments, Standard Oil Company systematically dispatched a team led by top headquarters executives for an intensive inspection of its assets, in particular its refineries. What do I know about the two business trips in 1910 to Kentucky, Nebraska, Wyoming, Nevada, Colorado, and California? Nothing except what we can glean from picture postcards. I did not find them in the Standard Oil Company archives in Austin, TX that I scoured. I found them in the Folger Archives. Have these deltiological objects been languishing in the Folger underground vault for four score and seven years waiting to be discovered to further illuminate the life of Henry Clay Folger?

There would have been no reason for widowed Emily Folger and her advisor, Henry’s nephew, Owen Fithian Smith, to send Standard Oil Company files to a Shakespeare library in Washington, D.C. Consequently, they sent ten boxes of books and business papers to New York in 1932, as attested by a letter from Richard P. Tinsley, treasurer of Standard Oil Company of New York on June 20, 1932 (Folger Archives Box 27). Mrs. Folger had written on the cover envelope “Dick’s bus. Books”. A trip report of the western refinery visits in 1910 might well have been among the documents in those boxes. When I queried the Standard Oil Company archivists at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin, they wrote back that surely the ten cases from Henry’s office would have been mixed in with the other company archives. ExxonMobil archives at the Center today include some 4 million documents.

And, why did Emily call Henry “Dick”? While a senior at Amherst College, Henry Folger sang the role of Dick Deadeye in Gilbert & Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore. While the couple had not yet met in 1879, Emily so cherished the idea of her husband singing in an operetta that she, when writing, often referred to him as Dick. Folger had a rich, basso profundo voice. He sang in the college glee club and in his fraternity quartet.

Fig. 1 Standard Oil Company delegation on inspection tour of western oil refineries

Okay, now who can spot Folger among the ten behatted men? The overcoats—and two pairs of gloves—betray the easterners, dressed to the nines with their oxfords and detachable high linen collars. The man in a black bowler wears a watch chain. The company gent on the far right appears to be the detail man, having brought from New York what may be reams of cost/yield statistics of company refineries. My money is on the gentleman on the far left as being a local refinery employee, with coarser hat, vest, jacket, and trousers. Six out of ten look at the photographer. Henry Folger wears a bowtie, a golf cap, and displays a graying beard. At about this time Folger was described in the press as “a lean, delicate, thin-bearded man.” Colleagues called him “a quite distant sort of person” (Briscoe Center for American History at UTexas Austin, H. C. Folger, Employee Relations folder).

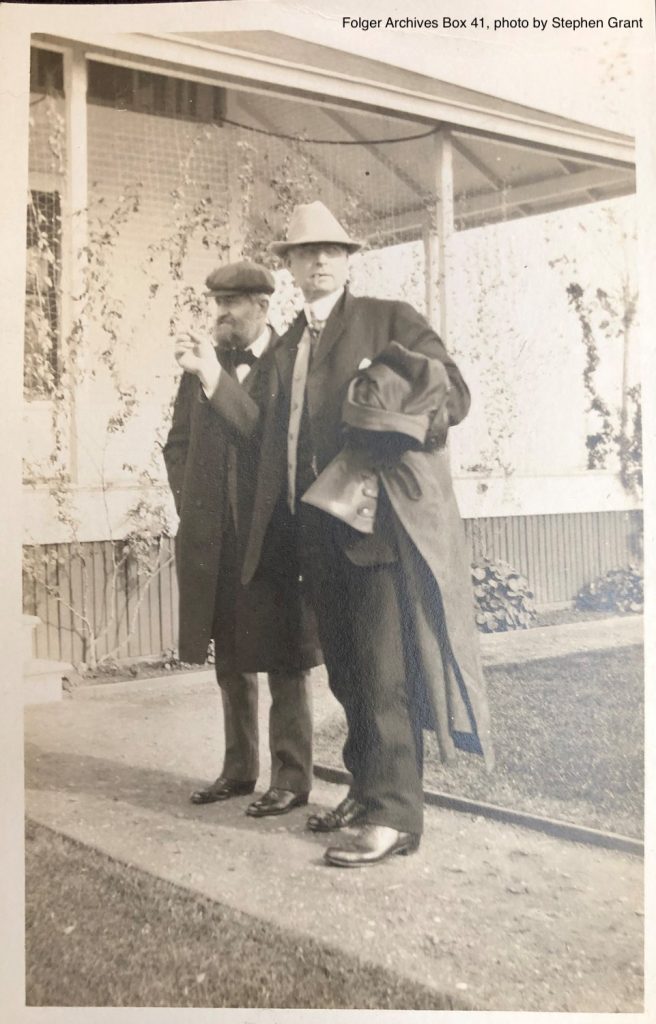

Fig. 2 Henry Folger with Walter Teagle during inspection tour of western oil refineries

We know from Henry’s scrapbook (Folger Archives box 29) that as a freshman at Amherst he measured five feet four and weighed 110 lbs. Since the man with a cigarillo hanging from his lips towers above Folger, there’s a good chance it’s Walter Teagle at six feet three. In Fig. 1, he’s plunked himself down center stage in the bottom row. For Fig. 2, he’s taken off his overcoat. Although Folger and Teagle are standing right next to each other, there is no interaction between them, and they look in two different directions.

Emily wrote after her husband’s death, “Not an exuberant personality, Henry always was reticent and possibly shy by nature” (Folger Archives Box 37). Folger and Teagle represented polar opposites in size as well as personality. Where is Bedford? Dunno. I printed out photos of A. C. Bedford from Google images and tried to compare. Nothing clearly matched. I emailed the ExxonMobil archivists in Austin to ask if they could identify members of the delegation. They replied that I could hire a researcher by the hour.

What I do have, however, may be more important. I have salary figures for the Three Cs.

In 1922, Folger’s last year as president of Standard Oil Company of New York before assuming the role of board chair, Folger’s salary was $100,000 (Folger Archives Box 41). In the same year, Bedford and Teagle each earned $125,000 (Folger Archives Box 41). In 2018 dollars $100,000 is $1.5 million and $125,000 is just shy of $2 million. The Three Cs were wealthy, but small change compared to the Charles Pratt fortune, which, in turn, was small compared to the Rockefeller fortune.

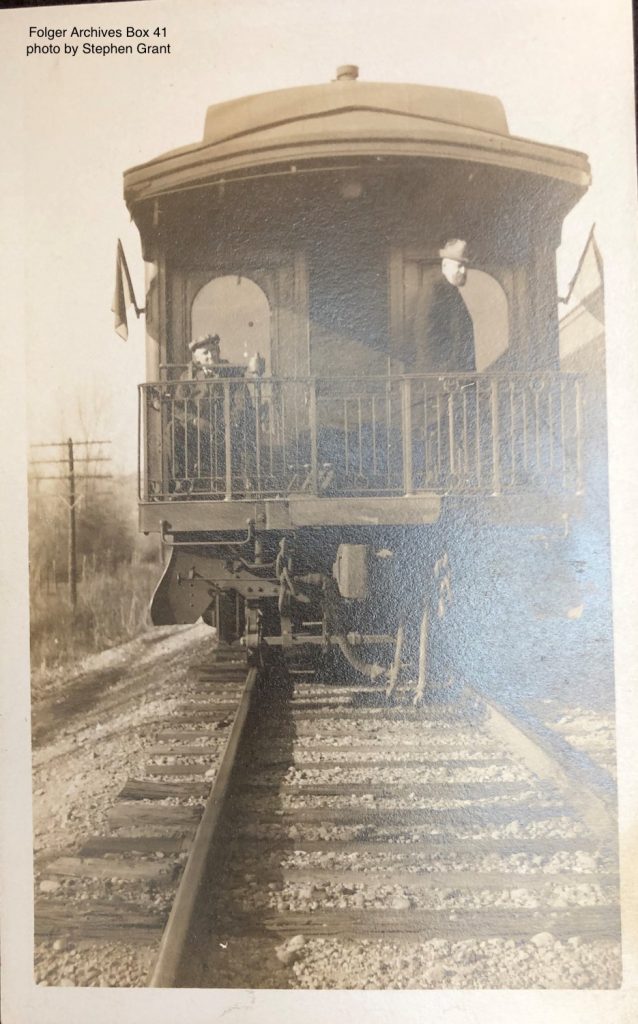

Fig. 3 Henry Folger standing in the caboose during Standard Oil Company delegation on inspection tour of western oil refineries

From the previous photograph of Folger, we now learn that he brought at least two hats on the trip out west. Folger had earned the reputation of being somewhat of a loner at Standard Oil. For lunch he eschewed the executive dining room at 26 Broadway, preferring to munch on an apple and feed pigeons in the park. I am not surprised to catch him in a solitary mood looking out over the guard rail. Could he be ruminating over his last laconic postcard message to Emily? Contemplating what message to send home on his next postcard? Look at the fancy oval glass on the two matching windows looking out on the tracks from the caboose. This is no ordinary railroad car. Standard Oil Company most likely commissioned the cushiest of special railway cars for its senior executives.

Have any of you collators been wondering to whom these postcards were sent? With what postage stamps were they festooned, and what messages were penned to whom? Do you frankly admit enjoying the opportunity I am giving you to read other people’s mail? Sorry, these black-and-white postcards were never written on or sent through the mail. All the backs are the same. Take a look.

Fig. 4 Message and address side of same postcard

Did you notice the word VELOX? It’s printed four times along with the “place stamp here” directive in what is called the “stamp box.” VELOX is code wording for what is called in the trade a “Real Photo Postcard” (abbreviation RPPC). This type of postcard comes from developing a negative onto photo paper with a pre-printed postcard backing. It has been used for small printing runs since 1900. Some deltiologists collect only this form of postcard. In this case, the resolution is not of high quality. Real post cards may well be the work of amateur photographers. Sometimes it may be an absolutely unique card.

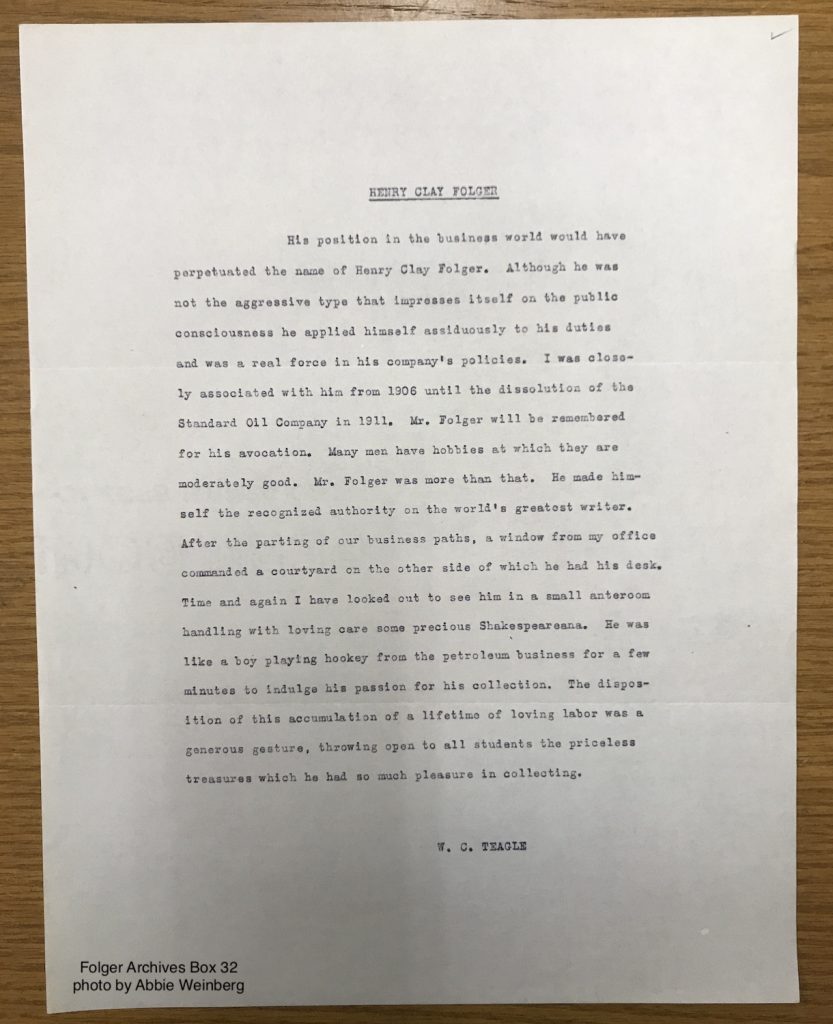

In August of 1932, in consultation with her nephew Edward Dimock, Emily Folger took steps to have a biography written about her late husband. For author, she decided on James Waldo Fawcett, a well-known journalist in Washington, D.C. with the Evening Star. Through the spring of 1933 Mrs. Folger met off and on with Fawcett to discuss elements that might make up the volume. Fawcett contacted many colleagues at Standard Oil, asking for written recollections. One idea was to produce a letter-book to be placed in the Founders’ Room. Alas, the biography came to naught, but some of the recollections survived.

Fawcett collected an impressive array of recollections from dozens of friends and colleagues (Folger Archives Box 32). Among the most poignant is that of Walter Teagle, who was able to study his polar opposite Folger when the collector did not know he was being observed:

“His position in the business world would have perpetuated the name of Henry Clay Folger. Although he was not the aggressive type that impresses itself on the public consciousness, he applied himself assiduously to his duties and was a real force in his company’s policies. I was closely associated with him from 1906 until the dissolution of the Standard Oil Company in 1911. Mr. Folger will be remembered for his avocation. Many men have hobbies at which they are moderately good. Mr. Folger was more than that. He made himself the recognized authority on the world’s greatest writer. After the parting of our business paths, a window from my office commanded a courtyard on the other side of which he had his desk. Time and again I have looked out to see him in a small anteroom handling with loving care some precious Shakespeareana. He was like a boy playing hookey from the petroleum business for a few minutes to indulge his passion for his collection. This disposition of this accumulation of a lifetime of loving labor was a generous gesture, throwing open to all students the priceless treasures which he so much had pleasure in collecting.”

Fig. 5 Teagle’s letter of remembrance about Henry Folger

(This post originally appeared on the Folger Shakespeare Library’s research blog The Collation December 10, 2019)

COMMENTS:

1 Comment

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Shakespeare Collector Henry Clay Folger and President Calvin Coolidge | Stephen H. Grant - […] for four years was Charles Millard Pratt, also from Brooklyn, who became vice-president of Standard Oil Company of Kentucky while…

- Happy Birthday, Henry Clay Folger! | Stephen H. Grant - […] way to the very top of two distinct lines of endeavor. From 1879 to 1928 he climbed the ranks…

Submit a Comment

CONNECT

I welcomed the private email from an Amherst College classmate putting the kibosh on my caboose. I refer to Fig. 3. Bob Holmes teaches me: “The ‘caboose’ you referred to was not a caboose, but a special private observation car. These were over the top luxurious cars for the railroad moguls. They were usually owned not by the railroad, but by the huge companies such as Standard Oil. Those companies paid for them to be attached to the end of trains whenever and whereever they wanted.” The best of commentators include an image. Bob did not disappoint. “Steve, as promised, here is a picture of two-foot gauge SOCONY # 14 tank car restored here in Maine.