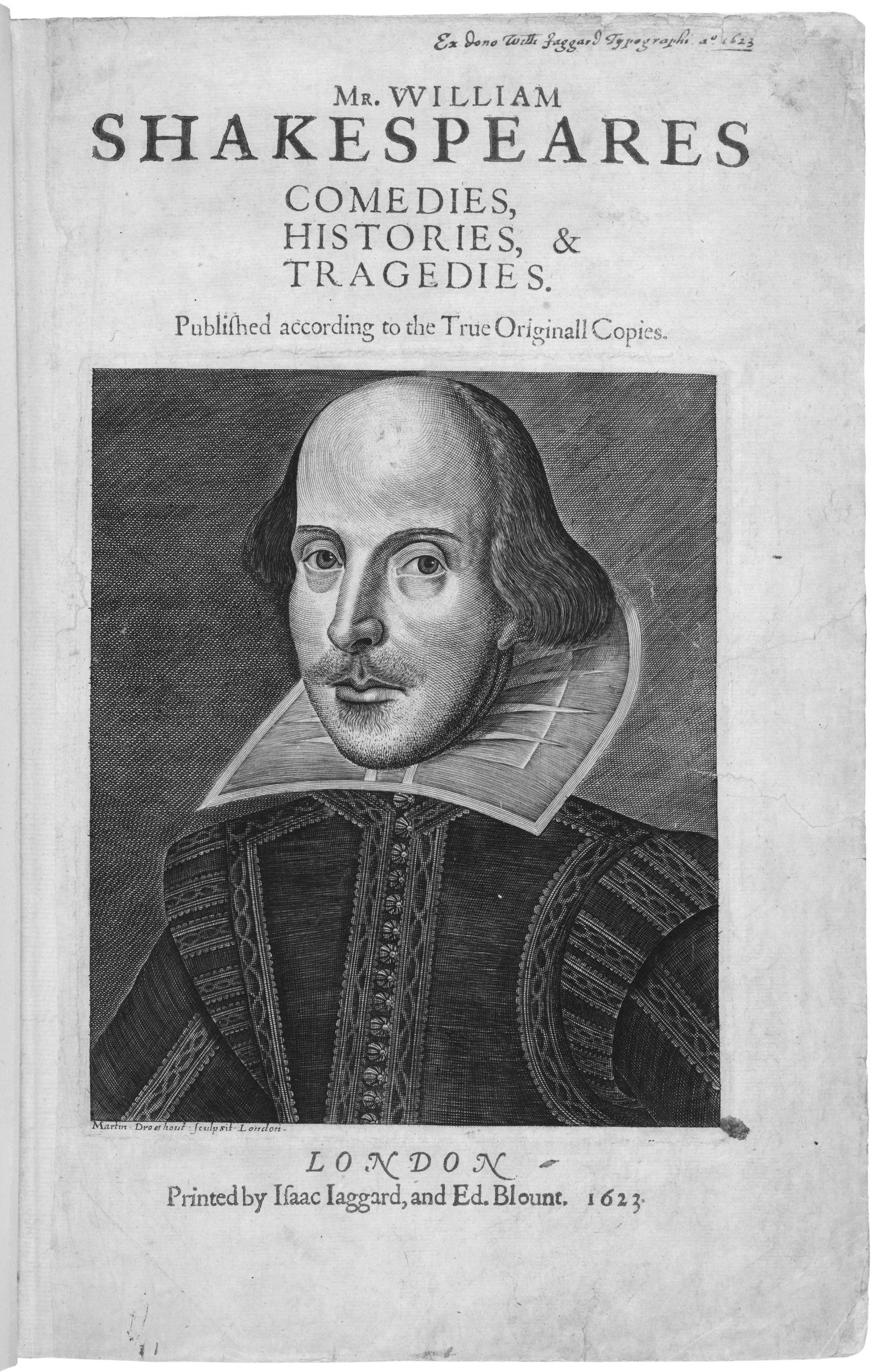

In forty years of book collecting, Henry Clay Folger managed to collect eighty-two of the 800 or so First Folios containing thirty-six Shakespeare plays compiled by two of the Bard’s actor friends, John Heminge and Henry Condell, and printed in 1623. They form the gemstone of the private research institution, the Folger Shakespeare Library, on Capitol Hill. When individual Shakespeare plays were first printed, they appeared in a small “quarto” format. A “folio” page is twice the size of a quarto page, over a foot high and about nine inches wide. The compilation that appeared seven years after Shakespeare’s death is the sole source for half of Shakespeare’s dramatic production. Eighteen plays (including Macbeth, Julius Caesar, The Tempest, and As You Like It) had never been printed before and would probably be unknown today without this early work.

Title page of Shakespeare’s First Folio, published in 1623, with the familiar portrait by Droeshout. The Folger Library possesses eighty-two copies of the First Folio, all different in some respects. Image from Collecting Shakespeare, used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Henry Folger called the First Folio “the greatest contribution ever made to the world’s secular literature.” His wife, Emily Jordan Folger, referred to the volume as “the cornerstone of the Shakespeare Library.” Amherst-educated Henry and Vassar-educated Emily were a childless couple from the Gilded Age. Together they collected 92,000 books about Shakespeare and his times, an average of six books every day. A vanished First Folio is rediscovered on average once a decade. The Folgers were not aware of the First Folio that resurfaced in the northern France town of Saint-Omer in September 2014. For 200 years, it had been misshelved among antiquarian books from the eighteenth century. The Saint-Omer copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio is incomplete and damaged. Thirty pages are missing, including the title page with the iconic engraving of the high-browed Bard and the entire play Two Gentlemen of Verona. However, when an exhibit on Anglo-Saxon authors opens in the Saint-Omer public library in 2015, this item will be its centerpiece. It is bound to attract hoards of both tourists and scholars. It is too early to evaluate the import of this recent find. It will take months or years for scholars to minutely examine all its pages to discover the secrets that lie within. One thing is immediately clear: this copy shows signs of significant wear and use. Not only are the pages worn, but the margins contain handwritten annotations. Certain antiquarian book collectors—such as J. P. Morgan or Henry E. Huntington, who competed with Folger for the same items—would have declined to acquire the volume as it was not complete or pristine. Folger would have aggressively sought to purchase the item. He was persuaded that a well-used First Folio would yield important clues for scholars. It was for study, not for show. Possibly one major feature in the Saint-Omer copy is related to religious beliefs. Saint-Omer lies only eighty miles across the English Channel from Dover. During Queen Elizabeth’s reign, an English Jesuit in the late sixteenth century founded a college in Saint-Omer. The college provided a haven for British Catholics persecuted in Protestant Elizabethan England who fled across the Strait of Dover. In the Middle Ages, Saint-Omer had been one of the forty most important European cities, boasting the fourth largest library. It contained a Gutenberg Bible, much rarer than a Shakespeare First Folio. There are now 233 known First Folios and about fifty original Gutenberg Bibles in the world. It is significant that the other Shakespeare First Folio in France is in Paris, and the other two Gutenberg Bibles in France are also in Paris. With the 2014 find, Saint-Omer has made a huge bound in celebrity reminiscent of its heyday 500 years ago. One small village in the Pas de Calais houses the two most famous secular and sacred volumes in the universe. Although the newly discovered First Folio already has a preliminary value of $4 million put on it, the library director has announced it constitutes a national treasure and is not for sale.

(This post was originally published on Johns Hopkins University Press Blog on December 10, 2014)

COMMENTS:

CONNECT

0 Comments