Emily Dickinson, Daguerreotype ca. 1847, Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

In 1874, Emily Dickinson wrote the poem:

Dear March – Come in –

How Glad I am –

I hoped for you before –

Put down your Hat –

You must have walked –

How out of Breath you are –

Dear March, how are you, and the Rest –

Did you leave Nature well –

Oh March, Come right upstairs with me –

I have so much to tell –

The following year, Henry Clay Folger of Brooklyn entered Amherst College in as a freshman.

Emily Dickinson and Henry Folger lived three blocks away from each other in Amherst, Massachusetts, for four years. There is every reason to believe they never met. Henry was studious on campus; Emily was reclusive at home.

Emily’s older brother, the treasurer of Amherst College, sent this note to Henry in 1876: “Your Term Bill for the present Term remaining unsettled, your attention is called to the Rule of the College in reference to same. Wm. A. Dickinson.” Folger was having difficulty paying his tuition bills. His businessman father was suffering from the Panic of 1873. Only through the generosity of Charles Pratt, the father of Henry’s roommate, was Folger able to graduate (Phi Beta Kappa) in 1879.

One week after graduation, Folger joined the Standard Oil Company in New York as a clerk working for the same Charles Pratt. Fifty years later, Henry stepped down as CEO of Standard Oil. What did Folger do with the fortune he earned as John D. Rockefeller’s trusted lieutenant? With his wife Emily Jordan Folger, who had earned an M.A. in Shakespeare studies at Vassar, he acquired the largest collection of Shakespeare-related items in the world.

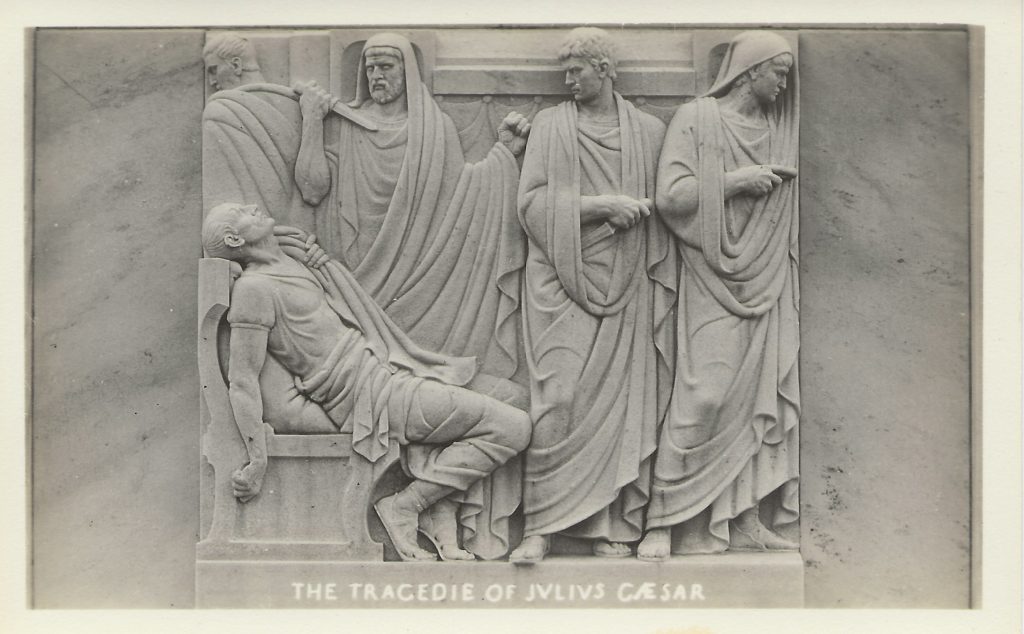

Folger contracted with French-born architect Paul Philippe Cret to design and build a marble monument to the Bard within sight of the U.S. Capitol: the Folger Shakespeare Library. The Folgers selected scenes from nine Shakespeare plays to adorn the exterior. Whereas in classical architecture carved bas-relief scenes were generally placed above pillars on the triangular pediment of a stately building, in the neo-classical edifice that Cret designed, the Folgers asked that the scenes be placed at convenient eye-level for passing pedestrians.

Postcard from Author’s Collection c1933, photo by Stephen Grant

In John Gregory’s sculpture illustrating Julius Caesar, Caesar has fallen and is dying. Brutus still has the knife in his hand. “Beware the ides of March,” a soothsayer warned the Emperor in Julius Caesar, Act I, Scene 2, as Caesar was going to the Roman Senate. Caesar replied, “He is a dreamer. Let us leave him.”

Collecting Shakespeare: The Story of Henry and Emily Folger is being released by Johns Hopkins University Press on March 15, 2014. As the author of the first biography of the founders of the Folger Shakespeare Library in eighty-two years, I have so much to tell—the atmosphere is one of fulfillment of a dream, rather than one of foreboding, on these Ides of March 2014.

(This post originally appeared on the Johns Hopkins University Press Blog on March 12, 2014)

COMMENTS:

CONNECT

0 Comments