In my writing career, I’ve had the opportunity to write articles based on interviews with two African heads of state:

—President Sangoulé Lamizana of Upper Volta, Africa Report, May-June 1973, pp. 29–33. (Note: Upper Volta changed its name to Burkina Faso in 1984.) The 1973 Lamizana interview took place in the presidential office at the principal military camp in the capital, Ouagadougou when he was head of state. No photography was allowed. The air conditioning was not working, and the president was dressed informally.

—President Senghor of Senegal, Africa Report, Nov.-Dec. 1983, pp. 61–64.

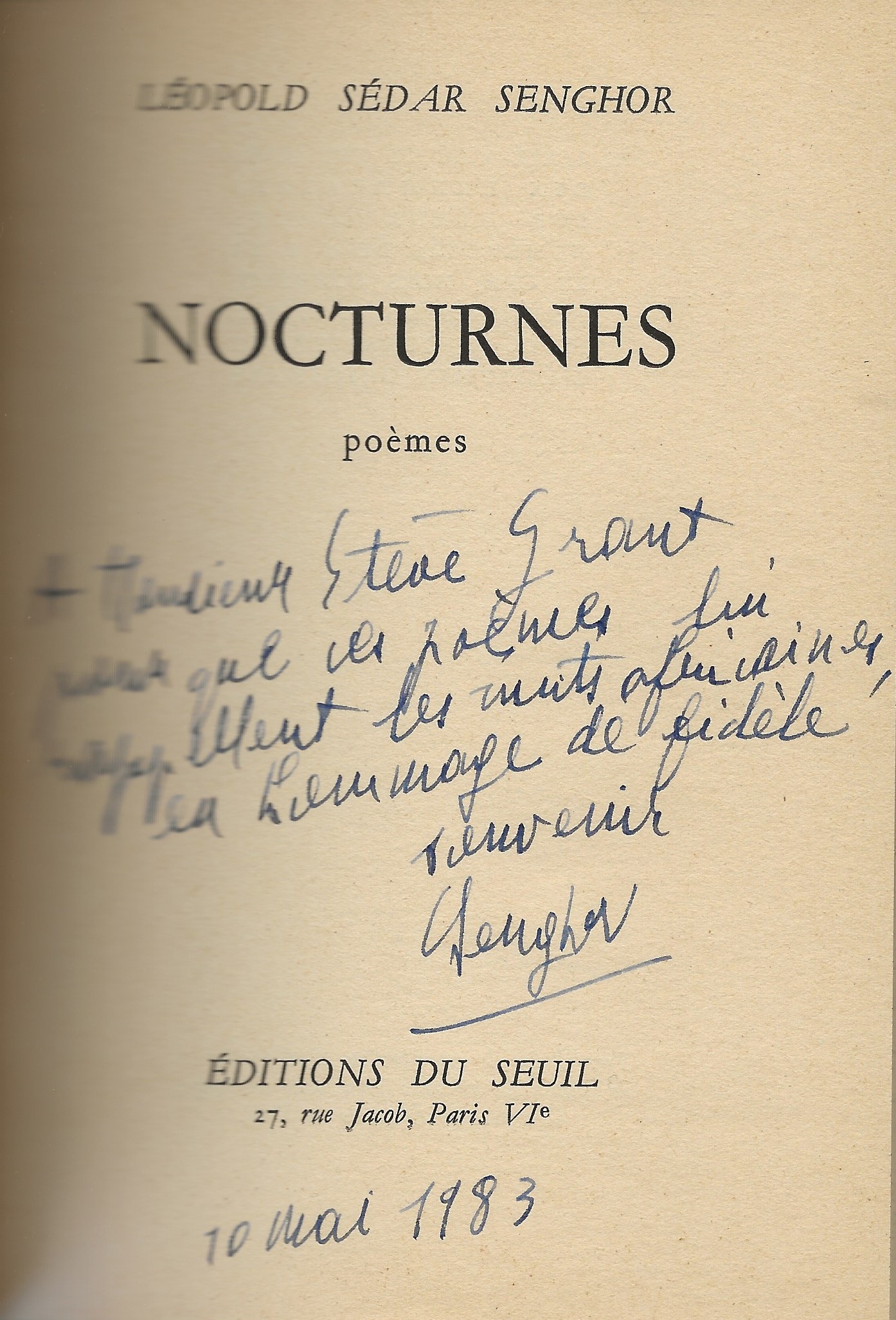

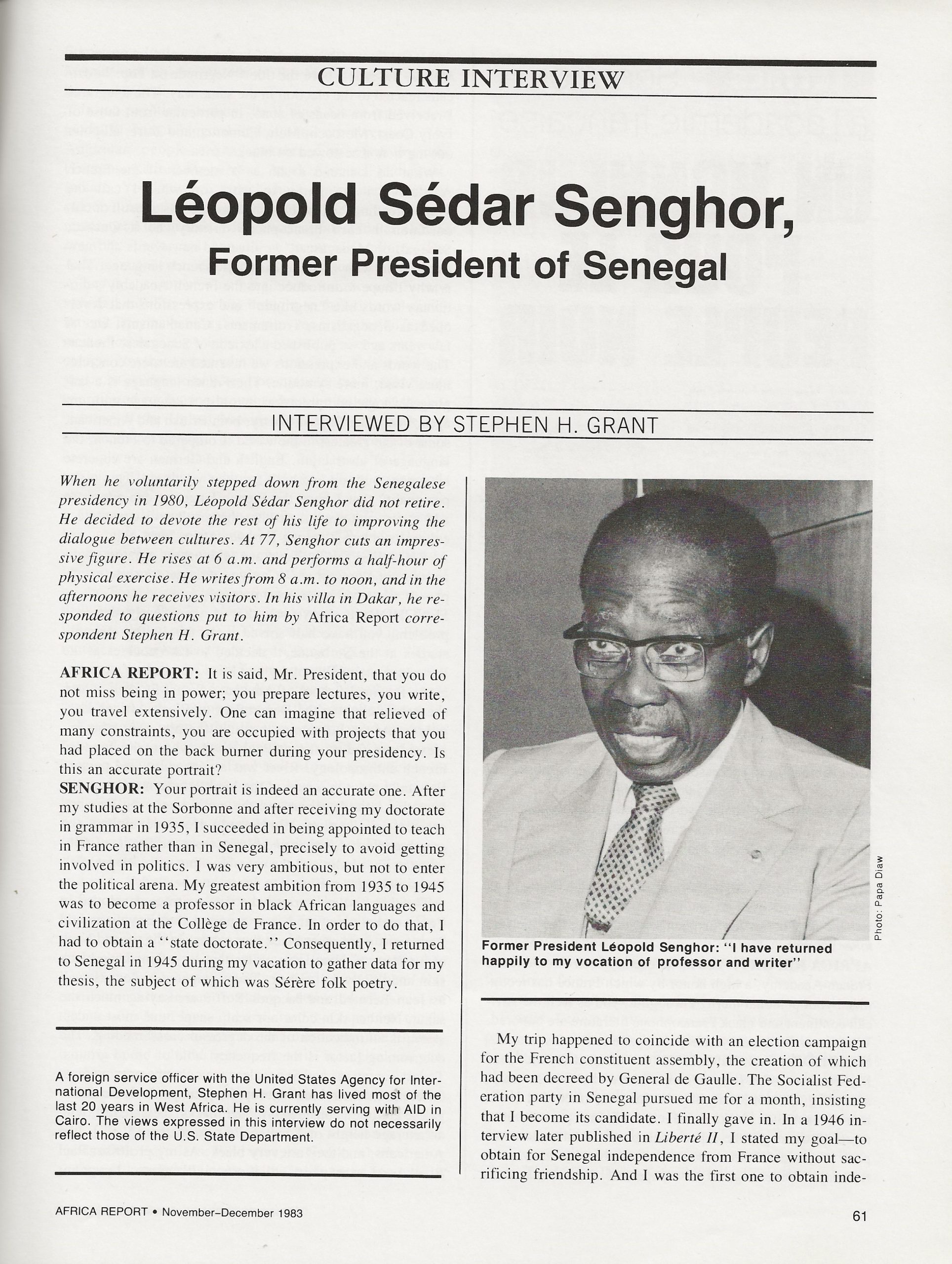

I had first learned about President Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal in 1963 by way of a course in Modern French Poetry at Smith College with Visiting Professor Jean Paris. What attracted me about Senghor was the fact that he was a “Poet-President.” He was first a published poet before being elected the first president of Senegal in 1960. When he stepped down in 1980, his prime minister, Abdou Diouf, took over. Senghor was also a scholar, having earned a doctorate in French Grammar in France, and he taught in France.

I had first learned about President Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal in 1963 by way of a course in Modern French Poetry at Smith College with Visiting Professor Jean Paris. What attracted me about Senghor was the fact that he was a “Poet-President.” He was first a published poet before being elected the first president of Senegal in 1960. When he stepped down in 1980, his prime minister, Abdou Diouf, took over. Senghor was also a scholar, having earned a doctorate in French Grammar in France, and he taught in France.

In 1964 I trained at Oberlin College for a Peace Corps assignment in West Africa. I lectured to my peers on Francophone literature, including several Senghor poems. I wrote essays in the Peace Corps journal En Principe about Senghor’s poetry.

In 1969 I took a Media Course while studying for my master’s degree at the University of Massachusetts’ School of Education. I put together a multi-media presentation of Senghor’s famous poem, “New-York.” Sam Ajiri, a graduate student from Enugu, Nigeria, volunteered to read the poem in English in his deep, sonorous voice. Another grad student in education, my neighbor, an African-American artist named JoeSam, joined him on stage playing Zambian drums. I manned slide projectors, one showing black-and-white photos of New York on one screen and on the other color photos of Africa. Senghor indicates in his books of poetry the instruments he likes to accompany his poems.

In 1972, President Senghor traveled to Ivory Coast to visit Ivorian president Felix Houphouet-Boigny and to meet with the Senegalese community. I took a picture of President Senghor standing in the back of a presidential vehicle in the second city, Bouaké. This is the earliest photo to accompany this essay.

In 1972, President Senghor traveled to Ivory Coast to visit Ivorian president Felix Houphouet-Boigny and to meet with the Senegalese community. I took a picture of President Senghor standing in the back of a presidential vehicle in the second city, Bouaké. This is the earliest photo to accompany this essay.

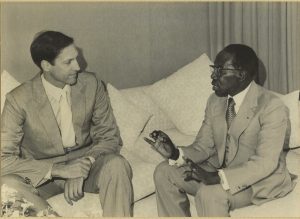

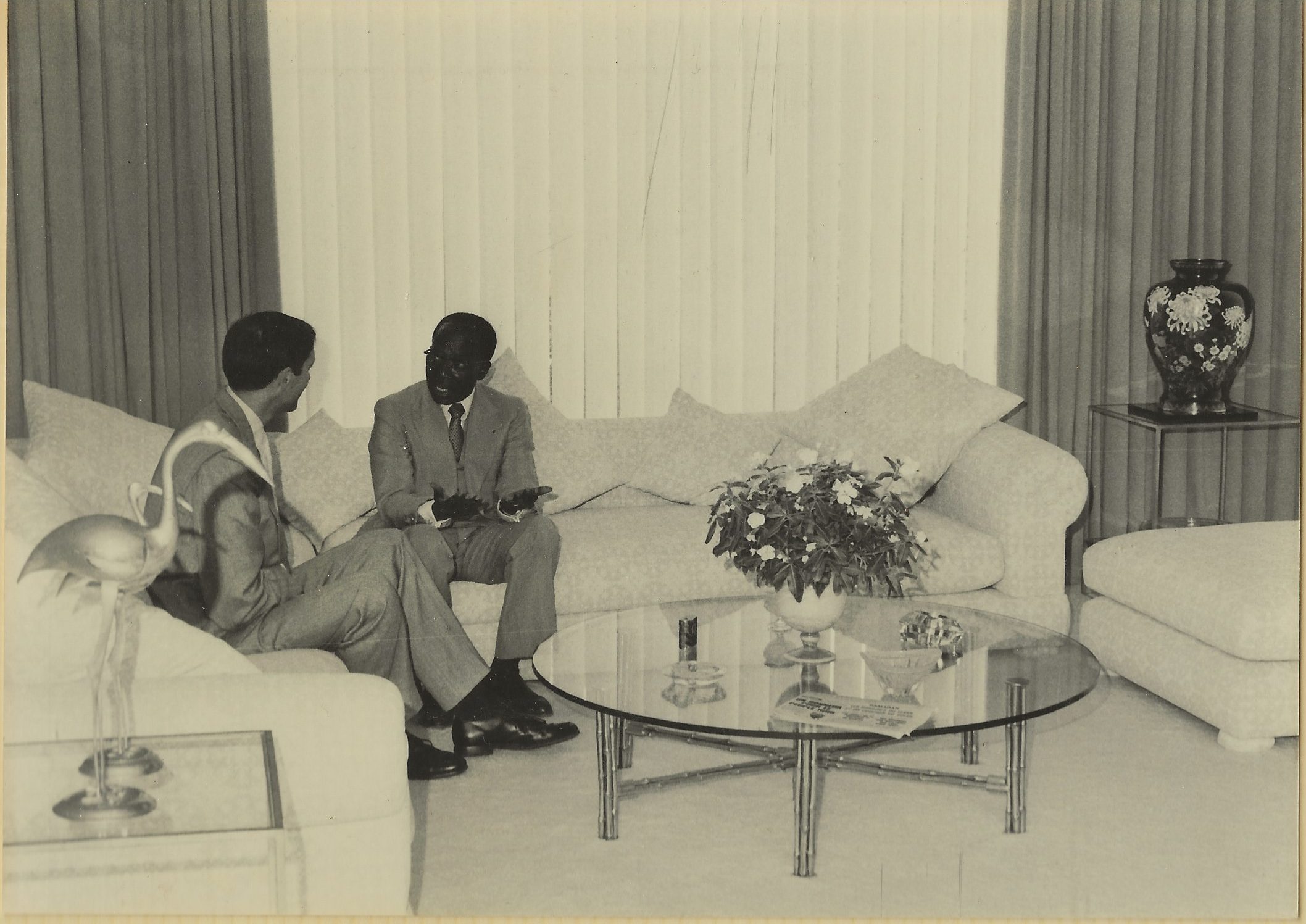

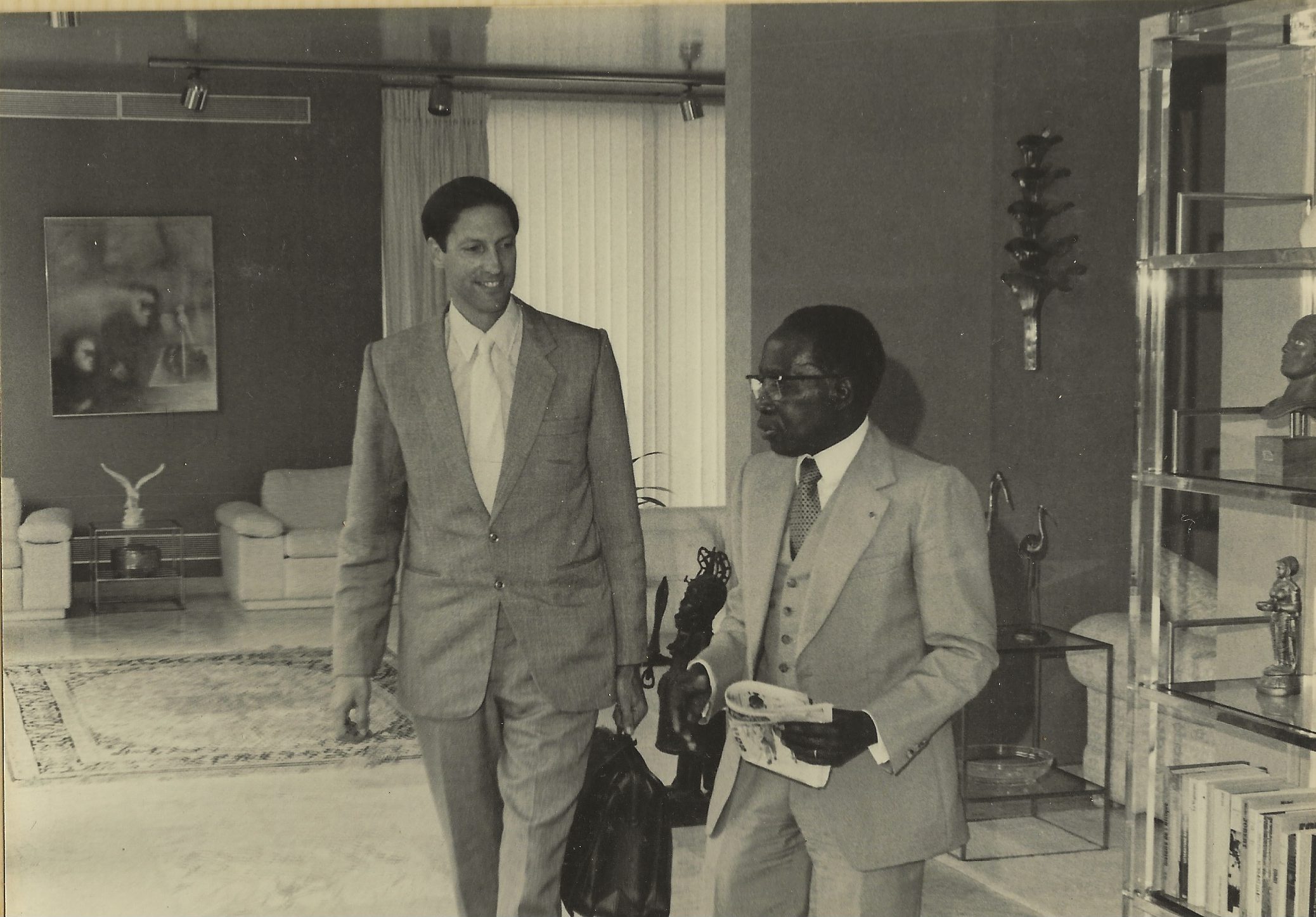

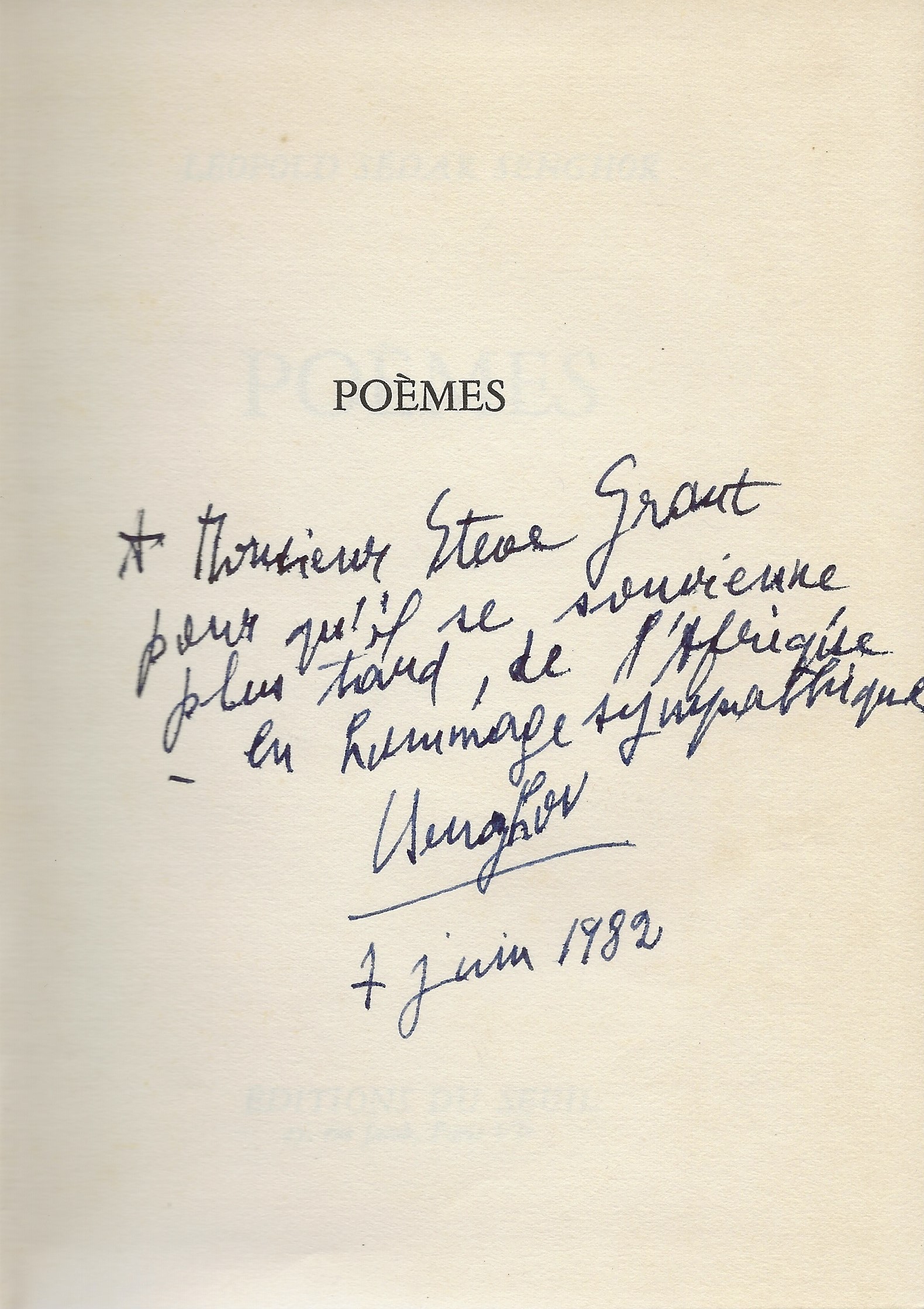

In 1982 I was working in Abidjan, Ivory Coast as Human Resources Development officer in the regional USAID office called REDSO, or the Regional Economic Development Services Office. I was called to consult with nearby USAID offices: Dakar, Senegal; Banjul, the Gambia, Conakry, Guinea, and Praia, Cape Verde Is. Long an admirer, I decided I would write to President Senghor to attempt to obtain an interview. I knew the president of the New-York-based African-American Institute, Don Easum. I wrote him and asked that if I wrote an article based on an interview with Senghor would Africa Report publish it? He encouraged me. I wrote Senghor out of the blue, and was quite surprised when he responded on Aug. 3, 1982 from Normandy, where he was vacationing with his (French) wife, Colette Senghor. He first excused himself for having delayed his reply. “I spend half my time traveling,” he explained (in French) before continuing, “You should not harbor excessive scruples. Send me a cable two weeks in advance.” That is what I did. The U.S. Embassy in Dakar facilitated the appointment and provided a photographer, the late Papa Diaw. I spotted the president’s avant-garde home (“Les Dents de la Mer” or “The Ocean’s Teeth”) from the air, as the plane prepared to land in Dakar-Yoff airport. My accompanying picture turned out grainy.

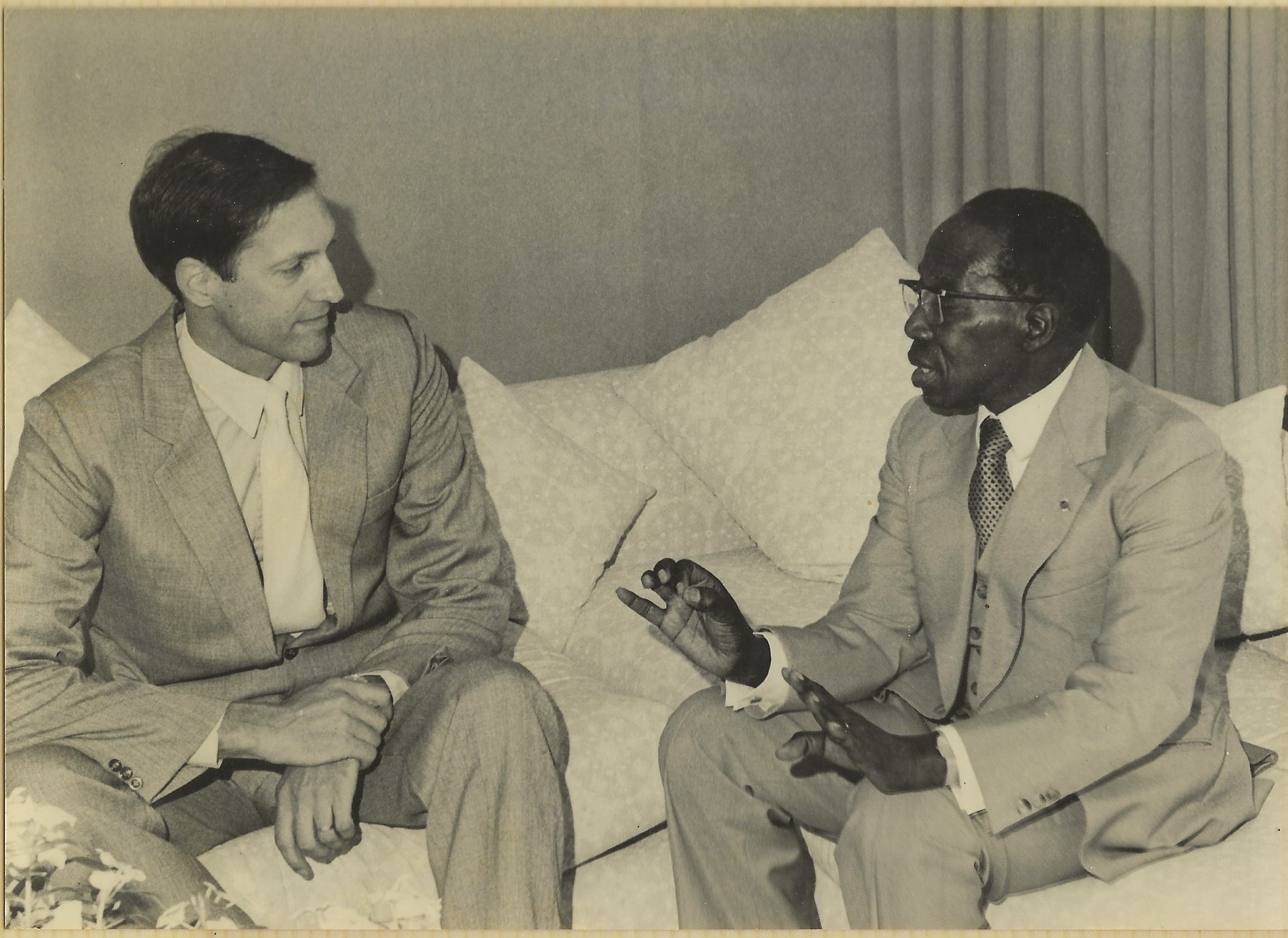

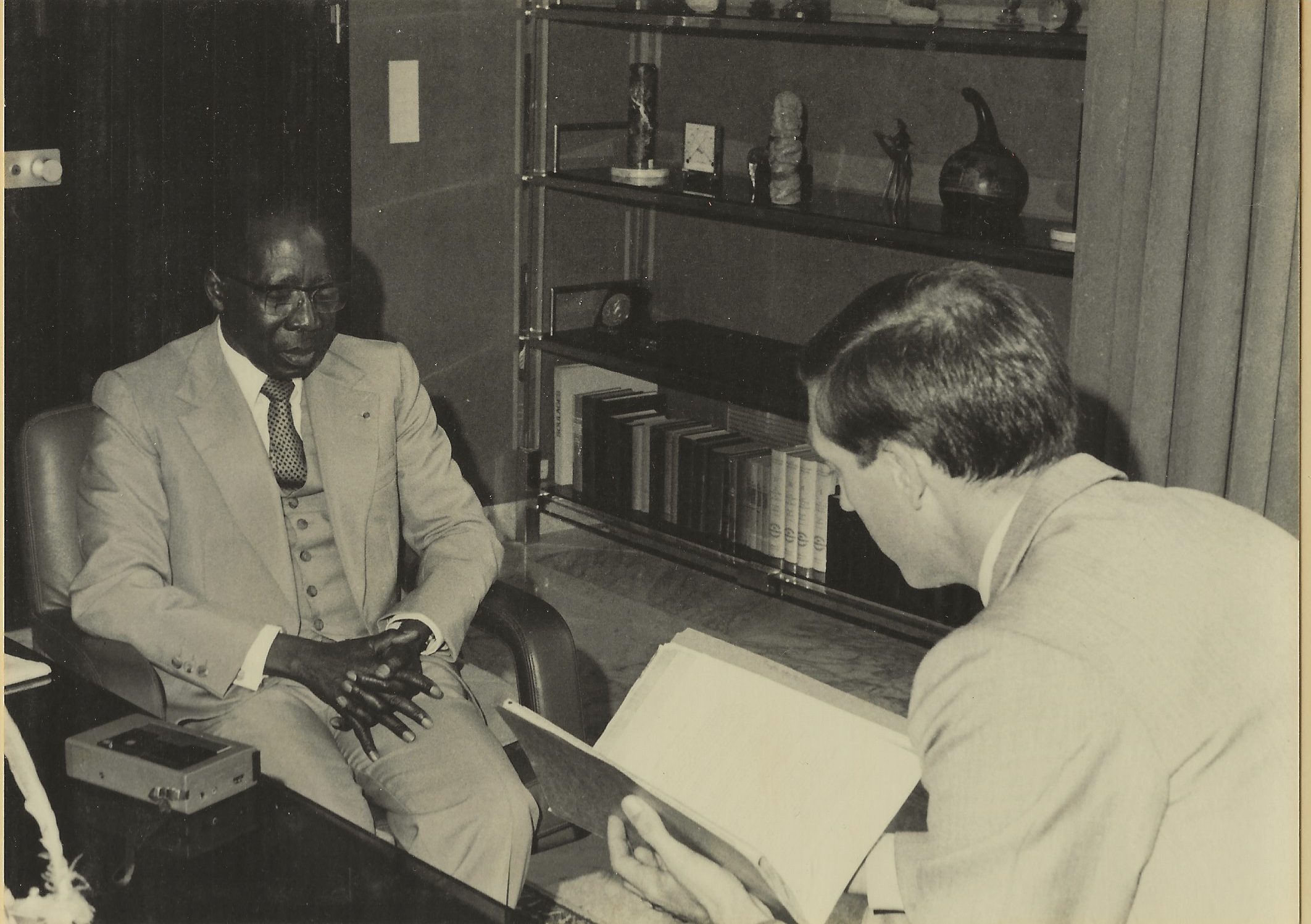

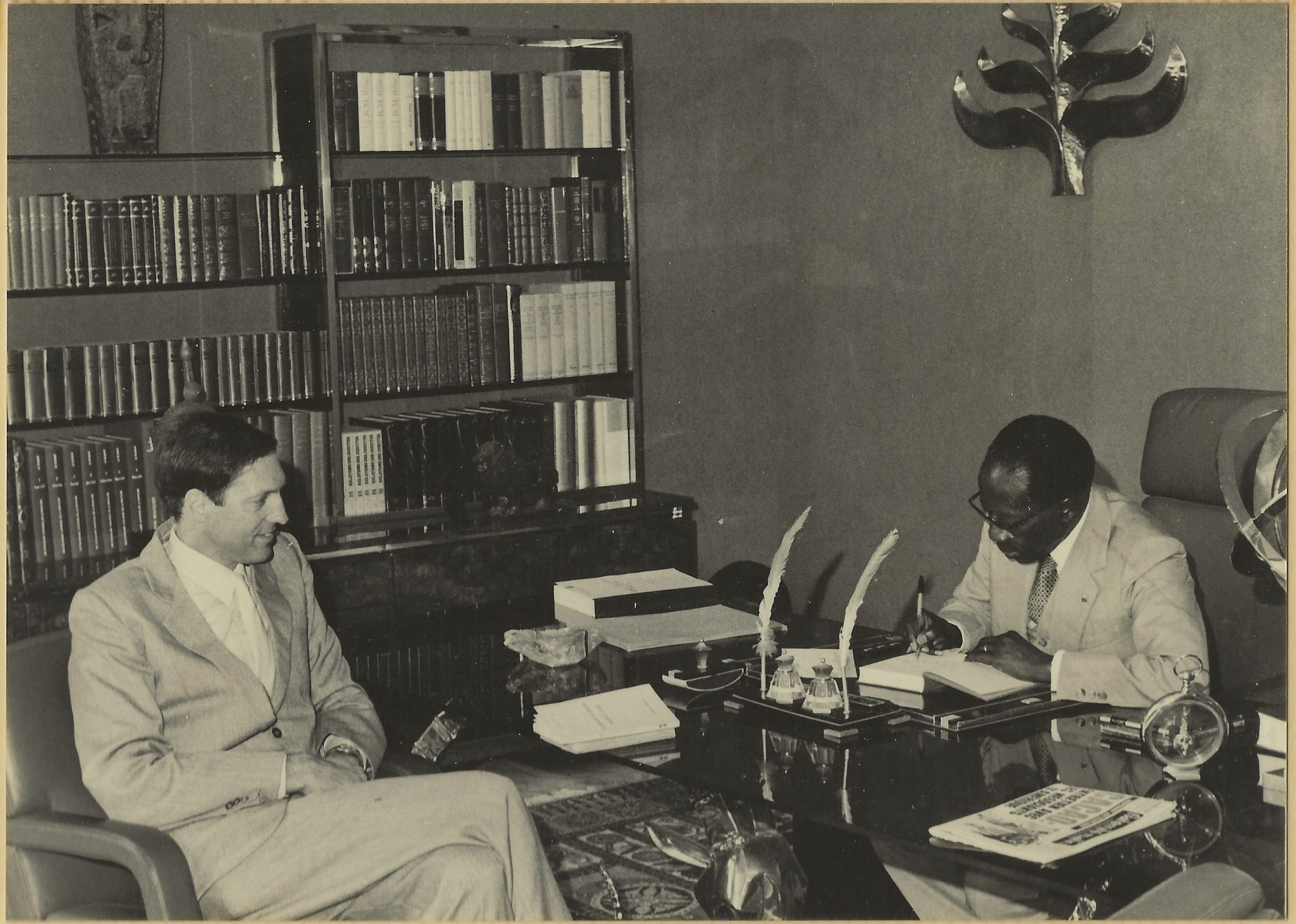

My 1983 Quo Vadis calendar fixes the appointment on Wed., June 15 at 11 o’clock AM. As historian and author Cyr Descamps likes to say, “in Senegal you can count on only two things to be on time: the ferry to Gorée and an appointment with President Senghor.” As I look back on it 37 years ago, it was one of the most thrilling encounters––savored over 90 minutes––of my life. Senghor shared an aphorism that has stayed with me since: “if you clearly define a problem, you have half solved it.” Mind you, I knew that President Senghor was comfortable receiving young American diplomats in his home. I had learned that the president was keen on perfecting his English, an attitude that manifested itself in the plum honor bestowed on the CAO (Cultural Affairs officer) at the American Embassy to give him regular English lessons. During our time together the president was totally absorbed answering my questions. There was not one sound that could be heard: no airplanes overhead, no pounding of plantain banana or yams in the courtyard. As I recall, no refreshments were offered. Just intense talk. On top of political and literary fame, for me President Senghor personified wisdom and courtesy.

My 1983 Quo Vadis calendar fixes the appointment on Wed., June 15 at 11 o’clock AM. As historian and author Cyr Descamps likes to say, “in Senegal you can count on only two things to be on time: the ferry to Gorée and an appointment with President Senghor.” As I look back on it 37 years ago, it was one of the most thrilling encounters––savored over 90 minutes––of my life. Senghor shared an aphorism that has stayed with me since: “if you clearly define a problem, you have half solved it.” Mind you, I knew that President Senghor was comfortable receiving young American diplomats in his home. I had learned that the president was keen on perfecting his English, an attitude that manifested itself in the plum honor bestowed on the CAO (Cultural Affairs officer) at the American Embassy to give him regular English lessons. During our time together the president was totally absorbed answering my questions. There was not one sound that could be heard: no airplanes overhead, no pounding of plantain banana or yams in the courtyard. As I recall, no refreshments were offered. Just intense talk. On top of political and literary fame, for me President Senghor personified wisdom and courtesy.

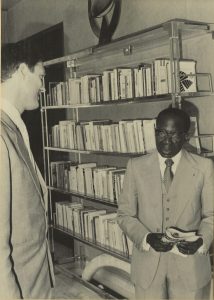

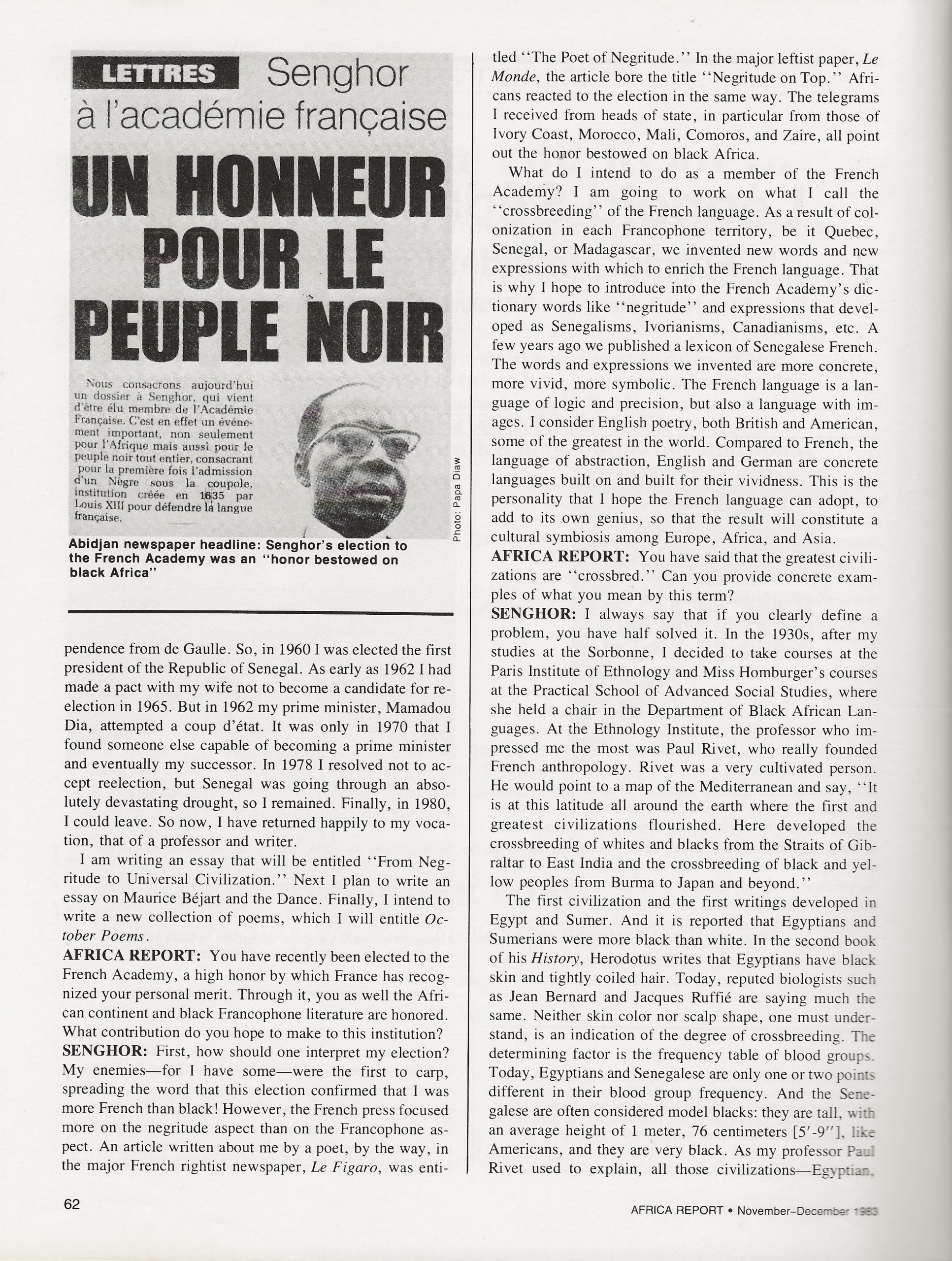

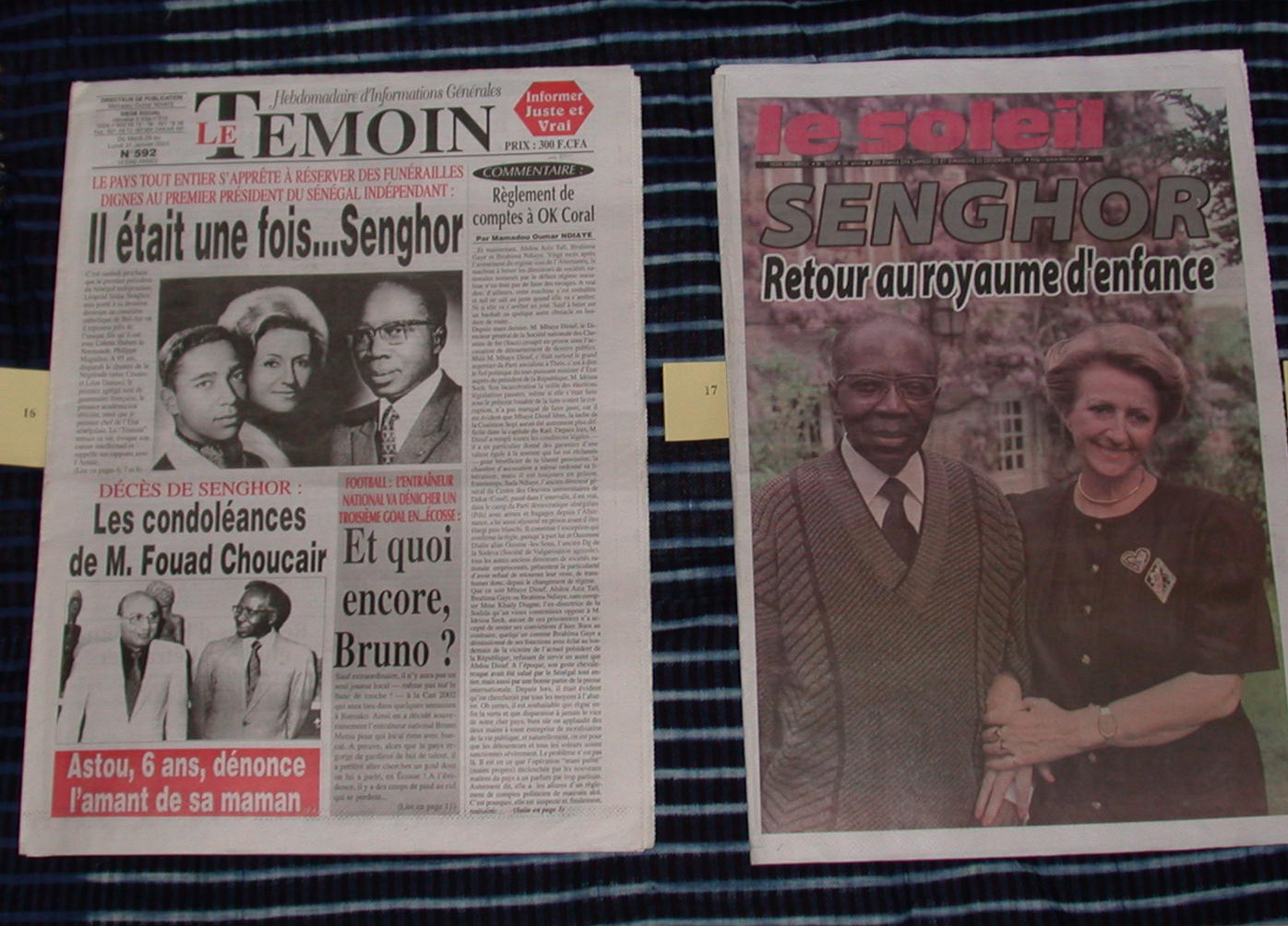

Actually, if truth be told, the president was slightly distracted during our discussion. The day before, the daily newspaper from Ivory Coast, Fraternité-Matin, had printed a front-page above-the-fold article on Senghor’s having been elected a member of the prestigious Académie française, the French Academy in Paris. I probably could not have brought him a more desired house present. You will notice it in four of the 24 images accompanying this article. The main headline was CACAO (cocoa), but no. 2 was Senghor’s academic honor. There was often a rivalry between the presidents of Senegal and Ivory Coast, both of whom had served as ministers in French cabinets. I am sure that as soon as I was out the door, Senghor sat down to read every word of how his honor was interpreted in the Ivorian press.

Actually, if truth be told, the president was slightly distracted during our discussion. The day before, the daily newspaper from Ivory Coast, Fraternité-Matin, had printed a front-page above-the-fold article on Senghor’s having been elected a member of the prestigious Académie française, the French Academy in Paris. I probably could not have brought him a more desired house present. You will notice it in four of the 24 images accompanying this article. The main headline was CACAO (cocoa), but no. 2 was Senghor’s academic honor. There was often a rivalry between the presidents of Senegal and Ivory Coast, both of whom had served as ministers in French cabinets. I am sure that as soon as I was out the door, Senghor sat down to read every word of how his honor was interpreted in the Ivorian press.

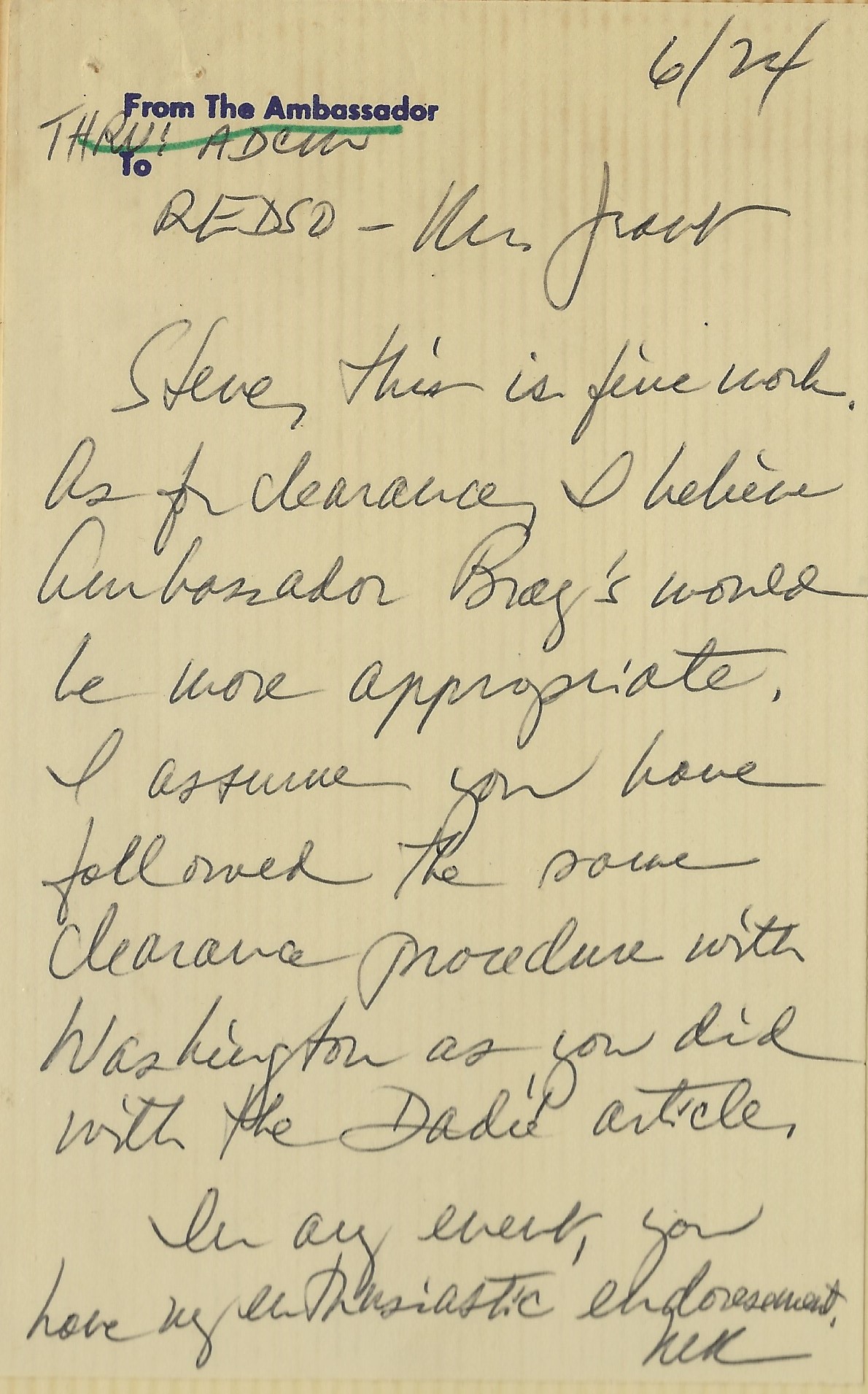

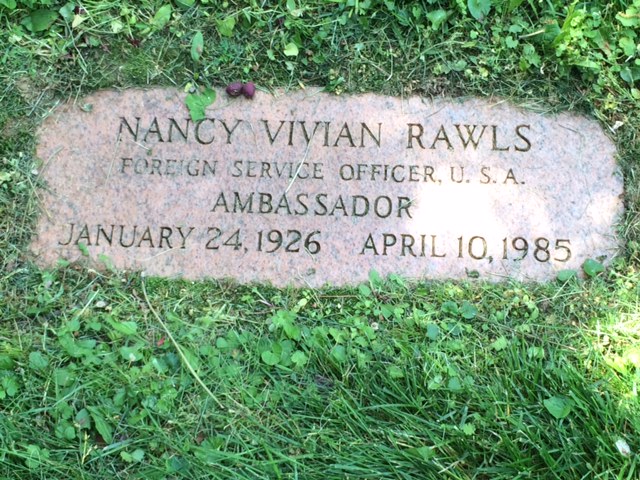

When you are a Foreign Service officer and write about a meeting with a head of state (in this case Senghor had stepped down three years before after 20 years as Senegalese president) it is required to obtain diplomatic clearance. I initially wrote to the American Ambassador in my country of assignment, Ivory Coast, Nancy V. Rawls. She replied in an accompanying note that protocol determined that authorization (it was granted) should come from the American Ambassador to Senegal, Charles W. Bray. Ambassador Nancy Rawls in her message refers to a previous article I had written on author and Ivory Coast Minister of Culture, Bernard Dadié (“The Making of a Writer: Bernard Dadié of Ivory Coast,” West Africa, Aug. 22, 1983, pp. 1953–54). I have supplied captions to photos illustrating this story. The final two photos are of the Ambassador’s gravestone and the Poet-President’s tomb.

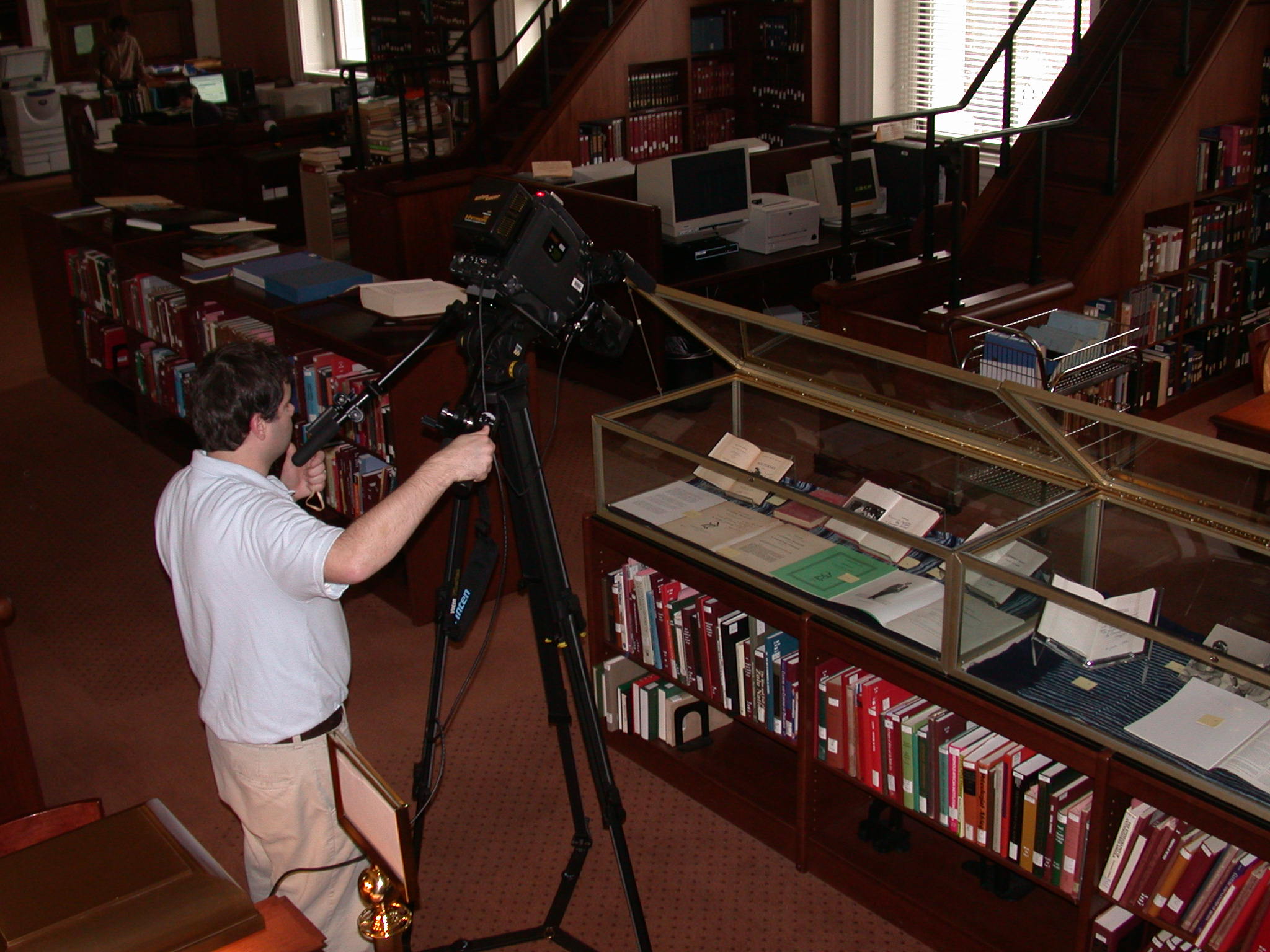

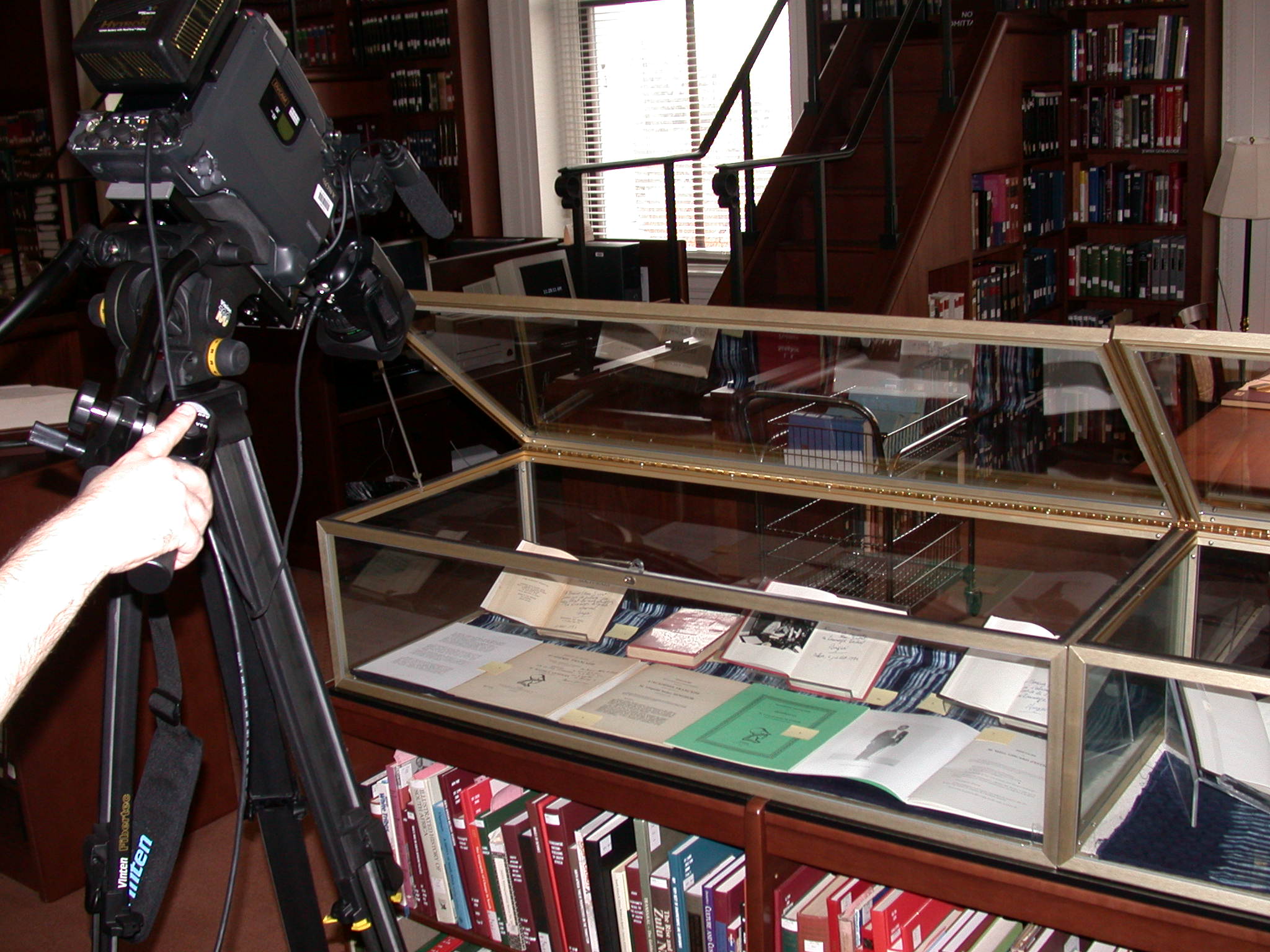

On Nov. 7, 2006, the Library of Congress welcomed visitors to the African & Middle Eastern Division (AMED) Reading Room to view an exhibit I assembled to commemorate 100 years since the birth of Léopold Sédar Senghor.

On Nov. 7, 2006, the Library of Congress welcomed visitors to the African & Middle Eastern Division (AMED) Reading Room to view an exhibit I assembled to commemorate 100 years since the birth of Léopold Sédar Senghor.

President Senghor died on Dec. 20, 2001 in Verson (Normandy), France. Senghor had been born on Oct. 9, 1906 in Joal-Fadiouth, a coastal town in Senegal. In October 2006, the African & Middle Eastern Division of the Library of Congress asked me if I would put together an exhibit to honor President Senghor on the centennial of his birth. I lent 21 items from my personal collection for the exhibit. See “Stephen H. Grant Collection of Literary material Relating to Léopold Sédar Senghor.” I prepared remarks for the opening of the exhibit on Nov. 7, 2006. See “Remarks by Stephen H. Grant at the Opening of an Exhibit at the Library of Congress, Nov. 7, 2006.” Eight illustrations will serve to capture the flavor of the exhibit.

SENGHOR INTERVIEW IMAGE GALLERY

The Library of Congress camera crew filmed the objects that the African & Middle Eastern Division staff had curated.

The Library of Congress camera crew filmed the objects that the African & Middle Eastern Division staff had curated.

From L to R: Marame Mbaye, Augusta Dieng, Mary-Jane Deeb, Fatou Kader, Marieta Harper. Deeb was Director of the African & Middle Eastern Division under whom Harper worked. The other three Senegalese ladies had all worked at USAID/Dakar.

COMMENTS:

CONNECT

0 Comments