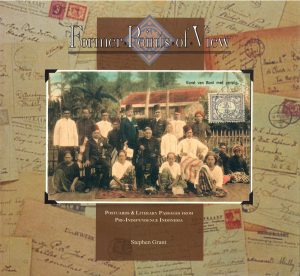

Book published in the capital Jakarta to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Indonesian independence.

I don’t know about yours, but my mid-life crisis struck me in Africa in 1980. I was visiting my first exhibit of old picture postcards in the National Library of Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. I knew Ivory Coast because I had been posted in the coastal West African country as a Peace Corps volunteer. Now I was working as an education officer for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

A collaborative work produced in Conakry, capital of the West African nation Guinea, Guinée française during the colonial period.

I have two Frenchmen to thank for the crisis: François-Edmond Fortier and Philippe David. David produced an inventory of the photographs Fortier took in Francophone West Africa between 1900 and 1912. Contemplating the exhibit, I marveled at the potential richness of every postcard: picture, stamp, cancellation, date, and message.I was hooked on the spot. My interest in postcards grew from that of collector to that of exhibitor, author of books and articles, and subject of radio and TV interviews.

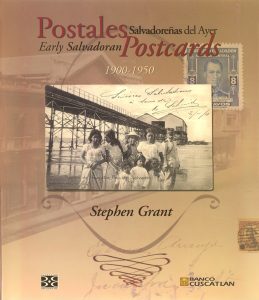

My career as a Foreign Service officer allowed me to discover the distant nations of Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea, Egypt, Indonesia, and El Salvador with multiyear postings. Outside of my diplomatic duties, I was able to have published in Guinea (1991), Indonesia (1995), and El Salvador (1999) three postcard books. I always carried old postcards around with me to show to my interlocutors, most of whom had never heard of postcard collecting.

One day in Bandung on the Indonesian island of Java, I handed my language instructor, Ibu Leila Hasyim, a pack of sepia postcards, thinking she could teach me some new vocabulary as we together examined the vintage photos on them.

One day in Bandung on the Indonesian island of Java, I handed my language instructor, Ibu Leila Hasyim, a pack of sepia postcards, thinking she could teach me some new vocabulary as we together examined the vintage photos on them.

Photo shown on left: 1930s postcard of a traditional Minangkabau house with sloping roofs like buffalo horns on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia.

When she got to one, her body stiffened and her hand trembled. She sputtered, “Rumah ini rumah saya” or “This house is my house.” She explained that the traditional house with a thatched palm roof had been replaced by a zinc roof in her day. She had never imagined that a postcard could have been made of her family’s home!

Grant explains picture postcards at his exhibit hosted by the Institut français Léopold Sédar Senghor in Dakar, Senegal

I had bought it at a Paper Show in Hartford, CT in a lot of fifty unsent postcards from the 1930s depicting views of the island of Sumatra produced by the Royal Dutch Packet Company that served passengers between Holland and the Dutch East Indies. I had offered the dealer half the asking price. He hesitated, glancing over to the snack bar in the corner of the large salesroom, before concluding, “Ya, I guess so. The wife’s still over there eating but she’ll kill me when she gets back.”

A bilingual book on the country of El Salvador, offering the little known facet of postcards as testimonies of bygone eras.

Some buy postcards to exchange with other collectors; some to put away in a shoe box for a future occasion. I bought postcards as a means to an end: to write books. They were of increasing sophistication. In Guinea, I was one of four collaborators. In Indonesia, I matched postcards with literary extracts. In El Salvador, the 5-lb. coffee-table book was bilingual. Once the books came out, I no longer needed the postcards; I sold them to other collectors or donated them to libraries and cultural institutions.

CLICK HERE to see one-minute video teaser at Smithsonian National National African Art. People ask, what country are you collecting now? I say, no country, one building: postally used cards of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC.

This article appeare on Wichita Postcard Club Nesletter, May 2020 issue. CLICK HERE to download the newsletter.

COMMENTS:

CONNECT

0 Comments